A Cave of Candles / by Dorothy V. Corson

Chapter 23

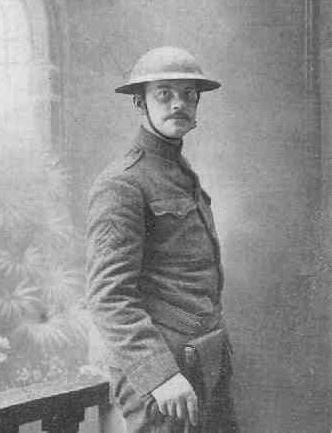

A Poet Linked to the Grotto -- Joyce Kilmer

Before leaving the subject of trees, it seems an appropriate time to share the story of another notable associated with Notre Dame, the Grotto, and another tree on campus -- Joyce Kilmer.

A random check of the University Archives data base produced a file containing an interesting 1943 brochure entitled University Statue Shrine Stories. It had been reprinted from, and published by, The Kerrville Times in Kerrville, Texas. By now, I was routinely going through every possible source connected with the Notre Dame Grotto. The following information produced yet another story associated with the Notre Dame Grotto.

Father Henry Kemper speaks of a former classmate:

My old Notre Dame classmate, Charley O'Donnell, who later became Poet Laureate of Indiana and president of his alma mater, Notre Dame, was a personal friend of the poet, Joyce Kilmer.

They say the big tree that shades Our Lady's niche 'a tree that looks at God all day and lifts her leafy arms to pray,' was the inspiration that made the patriot convert, Joyce Kilmer, famous, with his best-known poem. Kilmer volunteered in The Fighting Irish Brigade and was killed in action July 30, 1918 at the age of 32. The original flag of the Irish Brigade, carried through the civil war by General Meagher's boys was presented to Notre Dame last summer.(271)

Further on it mentions that Kilmer enlisted as a private seventeen days after the declaration of war by United States and Germany and within months sailed with the rainbow division to France. His second child Rose died after a brief illness which culminated in her death on September 9, 1917. Joyce went overseas soon after. His youngest son was born a month before he left.

Kilmer's best-known poem, "Trees", was published in September 1913. In July of the same year, Rose, nine months old, was dangerously ill with polio. Ellis Butler describes Joyce during those difficult times. He became a Catholic convert the same year.

He was altogether lovable and loved, he had a winsomeness about him. I think there are compensations, spiritual and mental, for the loss of physical power. It was this searing test of the spirit in the affliction of his daughter that fixed his religion.

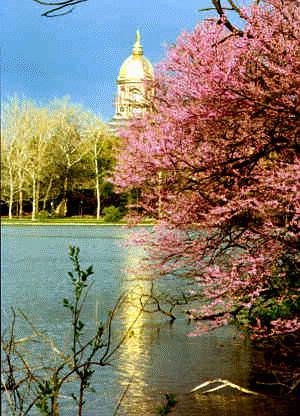

On a trip to the Notre Dame Grotto, I found, on the right side of the Grotto steps leading to the church, a huge stump that must have once been "the big tree that shades Our Lady's niche." I could only think, if it were true that it had inspired the poem "Trees," what a lovely story to be associated with the Grotto. Hardly a child goes through his schooling without having come in contact with Kilmer's poem:

|

Trees I think that I shall never see -- Joyce Kilmer |

The Scholastic reported:

Kilmer was noted as writing the poetry of the people, he mirrored their thoughts(272) . . . . Kilmer discovered in the most ordinary things rich and unsuspected meanings.(273)

His biographer, Robert Holliday, speaks of Trees And Other Poems, published in 1913:

The exquisite title poem now so universally known, made his reputation more than all the rest he had written put together. That impeccable lyric which made for immediate widespread popularity.

Following are more references to Kilmer by Holliday:

His song was as old as the hills, and as fresh as the morning. Precisely in this, in fact, is his remarkableness, his originality, as a contemporary poet; and in this will be, I think, his abiding quality. 'Simple and direct, yet not without subtle magic,' wrote Father James J. Daly, S.J., in a review of "Trees and Other Poems," printed in America, his verse, 'seems artlessly naive, yet it possesses deep undercurrents of masculine and forceful thought; it is ethical in its seriousness, and yet as playful and light-hearted as sunlight and shadows under summer oaks.'

Only the name of James Whitcomb Riley expresses in greater measure the rich gift of speaking with authentic song to the simplest hearts.

In letters sent home during the war in Europe, Kilmer wrote:

At present, I am a poet trying to be a soldier. To tell the truth, I am not interested in writing nowadays, except in so far as writing is the expression of something beautiful. . . . The only sort of book I care to write about the war is the sort people will read after the war is over -- a century after it is over.(274)

And from another letter, another Kilmer quote is shared:

'I'd rather be a sergeant in the 69th than a lieutenant in any other regiment in the world!' So a sergeant he remained, and one is not surprised to read, 'He was worshiped by the men about him.' He was killed on a reconnaissance patrol during the second battle of Marne, beside the Oureq River near the village of Seringes.(275)

Paul Scofield '20, captures that moment for all fallen soldiers in a touching tribute to Kilmer in the a 1919 Scholastic:

Suffer us to offer not only our condolences upon a death but also our congratulations. Death accepted in the Christian Spirit assures the safety of this man's soul. Possessed of that rare combination so alien to most of us, romance and common sense. And he never forgot that no matter how unpleasant life may be it is much too good for us. Thank God for God.

He religiously exclaimed and then joyously undertook the tasks that Life assigned him. How applicable to himself are the concluding lines of his 'Rouge Bouquet' [written for his fallen comrades]. 'Comrade true, born anew, peace to you / Your souls shall be where the heroes are / And your memory shine like the morning star.' And now in France there is 'in that rich earth a richer dust concealed, the dust of a soldier' newly strong in God's white company. The dust of an unconquerable spirit whose immortal songs shall never die.(276)

I was surprised to learn "some of his poems were set to music by his mother and published in England as songs."(277) A thesis written about Kilmer in 1927, by a friend of the family, Sister Roberta Bresnan -- "Home Life as a Theme in the poetry of Joyce Kilmer" -- speaks of Kilmer:

He had a quiet way of being genuine. He loved the simplest things of life because he was himself perhaps the simplest. His poetry expressed the remedy for all this world's woes, in one small word of deep and lasting significance, the word 'home.' When we designate it as a place it immediately shifts to a feeling, a person, an object. It may embrace an entire country or it may be confined within the perimeter of four walls.(278)

It reminded me of another Kilmer poem I'm fond of, "The House With Nobody In It." Being a lover of old homes, it left a deep impression on me. It captured not only the sadness of the ruins of a once loved home, but also the warmth and wholesomeness of a family that makes a house a home. Like "Trees" it is another example of his homey colloquial style.

|

The House with Nobody In It Whenever I walk to Suffern along the Erie track I never have seen a haunted house, but I hear there

are such things; This house on the road to Suffern needs a dozen panes

of glass, If I had a lot of money and all my debts were

paid Now, a new house standing empty, with staring window

and door, But a house that has done what a house should do, a

house that has sheltered life, So whenever I go to Suffern along the Erie track -- Joyce Kilmer |

I tried to visualize the Grotto when Joyce may have been there, the way he might have seen it, and a description of the campus penned by a writer in an 1886 newspaper came to mind. It confirms that the tradition of praying places among the trees was as much in evidence then as now:

The grounds around the college are laid out in finely shaded walks. As we pass over the grounds we notice that which always finds a tender spot in the hearts of all Catholics in the great number of oratories and abodes for prayer that are to be found in secluded parts of the grounds, that students on their walks may have an opportunity of offering to heaven their prayers undisturbed and with only the sky and the trees for witness.(279)

For such a memorable poem, as "Trees," to be associated with the Grotto would indeed be an honor worthy of every effort I might make to verify it.

Researching Kilmer

There was very little in the University Archives about Joyce Kilmer. A few mentions of lectures he made on campus, a few letters exchanged with Father Charles O'Donnell and Father John W. Cavanaugh arranging those lectures, but nothing personal, and nothing before the fall of 1914.

A number of books of poems, a doctorate written by a nun, a biography, gave me little information to go on. I combed through those books looking for evidence of his first visit to Notre Dame prior to that first lecture but found nothing.

One book written by a Brother Roberto did mention that he was working at the New York Times in 1914 and decided to supplement his income by arranging for lectures in eastern universities. He was poet and literary critic for the New York Times and The Literary Digest. Notre Dame was mentioned. Father O'Donnell, being a poet, it seemed reasonable his initial contact may have been with him and either before or after that first lecture they became friends and correspondents. Father Charles O'Donnell was also a chaplain where Kilmer was stationed during the war in Europe and he corresponded with Kilmer's widow, Aline, until his death.

"Trees" was first published in 1913.(280) There was no indication of when it was actually written. The prospects of finding any surviving family members who might have that information were remote. I again went back to the books in the Hesburgh Library stacks and this time took a closer look at a mimeographed plastic ring binder that had escaped close scrutiny the first time around.

It was a booklet compiled by the Campion College Of The Sacred Heart, Prairie du Chien, Wis. in late 1937 in memory of Joyce Kilmer. The booklet was entitled Kilmer And Campion. There was a photograph taken of Kilmer's daughter, a Benedictine nun, and his youngest son, Christopher, who was only a month old, when Kilmer went overseas and never returned. They were photographed together at the celebration.

Suddenly, it dawned on me. It might be nigh on to impossible to locate a lay person but a religious was another matter. Although the chances that she might still be living 57 years later were rather remote, I decided to give it a try. Library reference produced the telephone number of The Sisters of St. Benedict in St. Joseph, Minn. I was able to trace Sister Michael to St. Cloud through the order. "Yes," the Sister replied, "she is still with us but she is at another number."

Within minutes, I was talking to Kilmer's daughter at St. Cloud, Minn. She was delightfully friendly and most cooperative. She said she was sorry to report that to her knowledge no tree had been recognized as the one that inspired her father's poem, that it was her understanding that it was written at his home in New Jersey. She said her older brother might be able to remember more about it and she offered me his telephone number in Vienna, VA. It looked like I had found what I wanted, but not what I wanted to hear.

Thanking her for her help and her brother's number, I dialed it immediately finding at the other end of the telephone line a most hospitable Kenton Kilmer, oldest child of Joyce Kilmer. He confirmed his sister's impression. He said he also had a letter written by his mother explaining the origin of the poem Trees, as she knew it, to another inquirer and he would send me anything he had which might be of help. Many places, he said, including Kilmer's alma mater, Rutgers, had trees they felt had inspired Kilmer's poem.

When a large brown envelope arrived, I was most grateful for the material he had included. He said Richmond, NH, Prairie du Chien (Campion), and a Catholic Summer School and Retreat House on the shores of Lake Champlain were others said to have inspired his poem. He included pictures of the family home, the trees in front of it, and a copy of Kilmer's poem handwritten by him at the time.

He then described when and where Joyce Kilmer wrote his much loved poem:

Trees was written at his home in Mahwah, New Jersey on February 2, 1913. It was written in the afternoon in the intervals of some other writing. The desk was in an upstairs room, by a window looking down a wooded hill. It was written in a little notebook in which his father and mother wrote out copies of several of their poems, and, in most cases, added the date of composition. On one page the first two lines of 'Trees' appear, with the date, February 2, 1913, and on another page, further on in the book, is the full text of the poem. It was dedicated to his wife's mother, Mrs. Henry Mills Alden, who was endeared to all her family. It would be a challenge to build an anthology of famous poems dedicated or addressed to mothers-in-law. Edgar Allan Poe's To Helen would join Trees in beginning such a collection.

One day, shortly after I received this information, I was sharing my most recent Grotto research with my friend, Father Schidel, during a visit with him at Holy Cross House on campus. When I read the quote about Joyce and the Grotto I'd found in the obscure brochure at the archives, he began nodding his head (this before sharing any of the material from Kenton Kilmer). "What does that mean?" I asked, referring to his head shaking yes. He said he, too, had heard the same story over the years and he'd ask Father Carey, a nephew of Father Charles O'Donnell, the poet Laureate and Kilmer's good friend, if his uncle had ever mentioned Joyce and the Grotto.

Later he informed me that Father Carey did remember one comment his uncle made about walking around the lake and Grotto lawn with Kilmer and how they had stopped to admire what they both felt was a perfect tree. The one sheltering Our Lady and the Grotto perhaps? All of which could have been before the 1913 poem was written or, more likely, afterwards, in discussing it.

My friend, Father Jan, in his book, mentions how Joyce Kilmer visited their English class and recited his famous poem. Father Jan began his studies at Notre Dame in the fall of 1913, eight months after it was written and just weeks after it was published. He describes his remembrance of him in his book:

It was one of my happy graces to have Father (Charles) O'Donnell as a teacher in English. Into our classroom one day, he invited his fellow-poet, Joyce Kilmer, the author of "Trees." He himself recited his immortal lines with a commanding artistic touch. He was a mild-mannered man whose eyes betrayed a wealth of inspiring thoughts, and also a definite spark of courage, enabling him later to give his life for his country in World War I.(281)

Sister Madeleva, former President of St. Mary's College, and a poet, was also a friend of Joyce Kilmer in her early days as a nun. Sister Madeleva took a summer class in creative writing from Father Charles O'Donnell at St. Mary's and through him she met Kilmer. In her autobiography, My First Seventy Years, she speaks of her friendship with them:

More than once Joyce Kilmer came with Father O'Donnell to visit. Their minds were quick with poems waiting to be written. The importunities of war pressed. Both men volunteered for service. Both went overseas. Joyce was killed in action on July 30, 1918, near Ourcq in France and buried beside a stream that bears the same name. Father blessed his grave before coming home. Aline, his wife, and I corresponded occasionally until her death. The children, Sister Michael, the Benedictine daughter, and Kenton with his artist-wife and children I prize as friends.(282)

Unfortunately, Sister Madeleva's grade transcript for the date of that creative writing class and her letters and papers gave no clues to her first meeting with Kilmer on the St. Mary's campus. However, one of her poems being about candle-light, seems fitting to include in a segment about poets and the Grotto. Would that this portion of it might be placed at the Grotto as inspiration for all who visit there, in part:

|

Candle-Light Day has its sun, -- Sister M. Madeleva, C.S.C.(283) |

The next time I saw Father Carey he confirmed the story about his uncle walking around the lake with Joyce Kilmer and pausing to admire that "perfect tree" near the Grotto. Father Carey seemed to have the answer to almost every question about the campus I asked of him.

One day I heard of the existence of a Colt .25 semi-automatic handgun supposedly used by, Father Nieuwland and Professor Greene, leading American Botanist, and Professor of Botany at Notre Dame, to shoot specimens of leaves from the trees on campus in the 1920s. It was thought the gun was still in a center drawer of the desk in an office Nieuwland once occupied in the Science Building.

It seemed just a tall campus tale but I decided to ask Father Carey about it anyway. Once again, I found him a ready source of information about the campus. "That's a new one on me," he said, "but I'll be glad to check it out for you. The Professor who has that office lives in Corby Hall with me and we regularly play cards together. "I'll ask him about it."

On my next Friday visit to Holy Cross House, Father Carey again passed on the confirmation. "It's there all right," he grinned, "and its been there through every person whose had that desk since." I couldn't help but smile -- and so has everyone else I've told the story to -- in trying to envision this famous pair of scholars collecting specimens, too high to reach, with a Colt .25 pistol. One more tale about the campus confirmed and this one, appropriately, about trees. Later I found written evidence that this story was true. I also found evidence that Father Nieuwland used a rifle for the same purpose when he was on field trips in the wilds.(284)

Kilmer was quoted as saying in the Kilmer And Campion book:

I can honestly offer 'Trees' and 'Main Street' to Our Lady and ask her to present them as the faithful work of a poor unskilled craftsman, to her son.(285)

All of which shows that Our Lady was in there somewhere. Since the priest who wrote the brochure with the Notre Dame Grotto reference, was also a friend of Father O'Donnell, undoubtedly he might have been repeating something he remembered him saying about Kilmer and used the "they say" because he couldn't confirm it. Unfortunately, neither could I.

In my letter to Kenton Kilmer I quoted Father Schidel's thoughts on Kilmer's poem. He said that Belloc, a fellow poet of Joyce, spoke of "poetry being the distillation of the mind." This could mean that even though Joyce wrote the poem in the bedroom of his home, he might have been affected by trees he had seen in many localities and the poem "jelled" in verse upon looking out his window at the trees in his yard. In other words, we know where the poem was written, but probably only God knows where and when it was inspired.

Kenton's reply wrapped up my research admirably:

Mother and I agreed, when we talked about it, that Dad never meant his poem to apply to one particular tree, or to the trees of any special region. Just any trees or all trees that might be rained on or snowed on, and that would be suitable nesting places for robins. I guess they'd have to have upward-reaching branches, too, for the line about 'lifting leafy arms to pray.' Rule out weeping willows.

. . . I think Father Schidel's opinion that you quote is just right and in complete accord with what my mother and I agreed on. Dad meant trees in general, was surely thinking of the trees he was looking at, and probably of trees he had seen in the past, such as the famous one on the Rutgers campus. But what he was thinking and saying applies equally to trees he didn't see until later, or trees he never would see. Dad would surely be pleased with Father Schidel's citation of the Belloc quotation, for its aptness to the subject, because Dad was a fervent admirer of Belloc's poetry. He wrote the introduction to the American publication of Belloc's Verses.

. . . It is plain from comments in my father's letters, and the quoted remarks such as you cite, that Dad's devotion to Christ was always joined with the love of His Mother. I am sure that a grove of trees dedicated to the Blessed Virgin could have inspired him to write such a poem as 'Trees', if the poem had not already been written.(286)

In the course of a later telephone conversation with Kenton Kilmer, I found another connection with Notre Dame. In his letter he mentioned that he had worked for many years at the Library of Congress. On the phone, he shared this added remembrance associated with the University. He told me that when he was a young man he was invited to teach at Notre Dame and declined because he didn't think he was up to teaching young students. Then he chuckled, and told me, that instead, he wound up having a large family and got his training firsthand.

I had proof that Kilmer was on campus in 1913, the year he wrote and published "Trees." However, I had no evidence to prove that he had visited the campus and the Grotto prior to the time he wrote it, although it was possible. All together, it was a thoroughly enjoyable brief conversational encounter with the children of Joyce Kilmer. And short of an affirmative answer, I couldn't have asked for a more satisfying conclusion to my study of Kilmer and his association with the University and the Notre Dame Grotto.

|

Joyce Kilmer's "Trees," and Tom Stritch's view of the campus from his book, My Notre Dame, express, so well, the warmth and welcome we receive from trees: Few American colleges can rival its layout, none its trees. Of all the things to look at around Notre Dame I think I like the trees the best. . . . I seldom look at that island without thinking how lovely its redbud trees look from the Grotto lawn in the spring.(287) Another appreciator of trees, Father Cornelius Hagerty, an avid canoeist, made this interesting observation about their appeal to lovers of nature: "Trees stand still and let you look at them and are there in all seasons." In my imagination, I can picture Joyce Kilmer now, circling the St. Mary's Lake with Father O'Donnell, pausing in the shade of the Grotto lawn and admiring that "perfect tree" shading Our Lady's niche. |

Coincidentally, another Father O'Donnell, Rev. Thomas J. O'Donnell, C.S.C. '41 (no relation to President Charles O'Donnell) captured, as well, the essence of Kilmer and his poem, "Trees" in an article about the Grotto in a 1963 Scholastic. It is especially fitting to share here because in it he speaks of Kilmer:

It has been a favorite with visitors at all times; and during the spring and autumn those who live at Notre Dame seek it instinctively for coolness and attractiveness.

The canopy of trees, digging their roots into the unhewn rock, is the proudest grove on campus. And rightly so. These trees are a garland of green on a crown of rocks. They have lived up to all the beauty of Kilmer's poem . . . as all trees must. But these have done more. They have listened to May songs; they have watched flickering vigil lights; they have stood as silent sentinels while anxious prayers and burdened hearts lifted hopeful eyes to Our Lady. The trees of the Grotto -- if they could speak -- would speak only in a whisper. . . .(288)