| The Gamut/Hexachords |

|

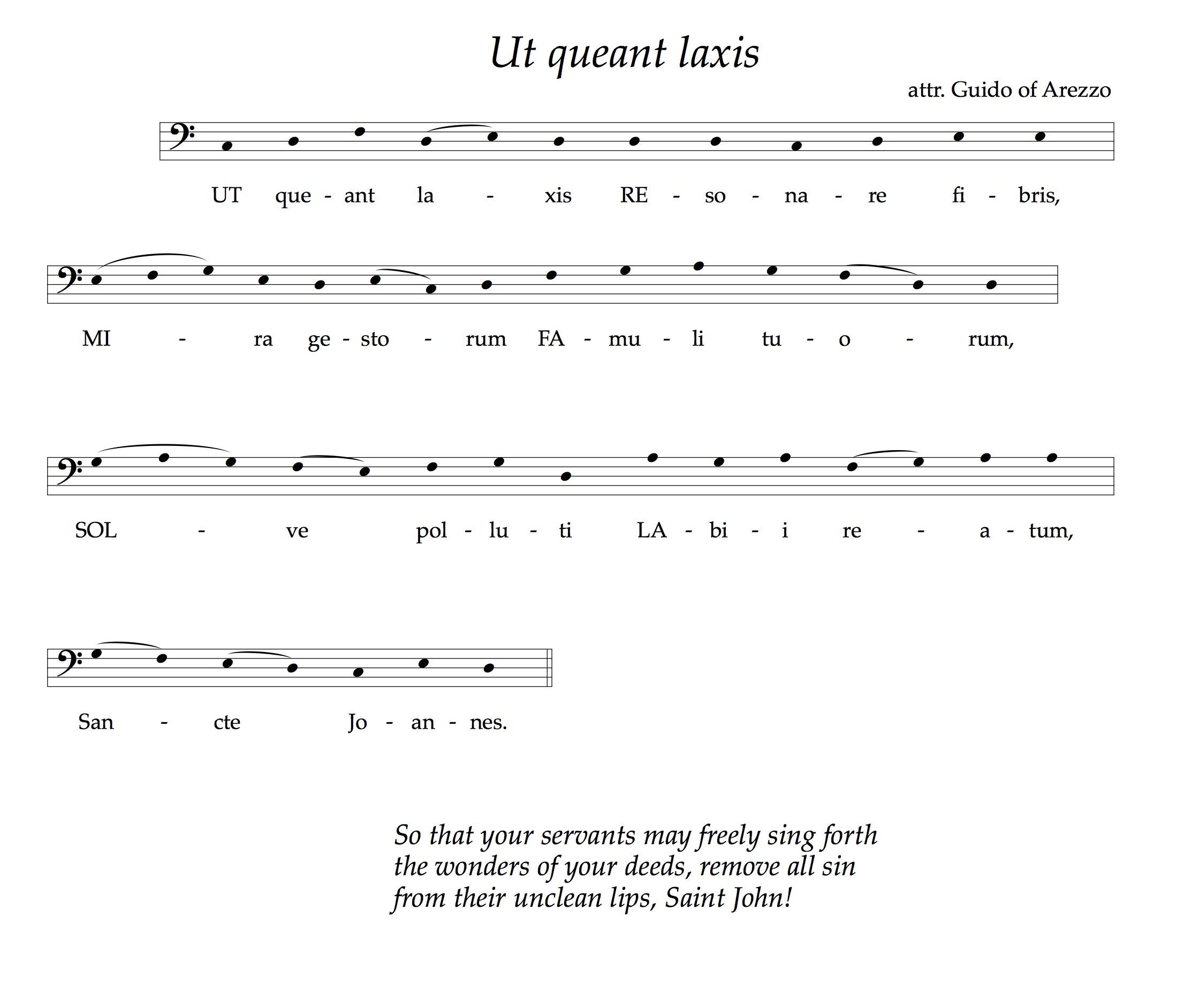

Guido of Arezzo’s Hexachord Guido of Arezzo (Aretinus) (ca. 991-after 1033) is said to have named the notes of his hexachord, notes extending from C upward to a, from the first syllable of each line of a hymn, each new phrase of which begins with a note one pitch higher than the first note of the previous phrase. The hymn, Ut queant laxis, a tribute to Saint John, comes down to us with several melodies; the melody below is the one associated with the story:

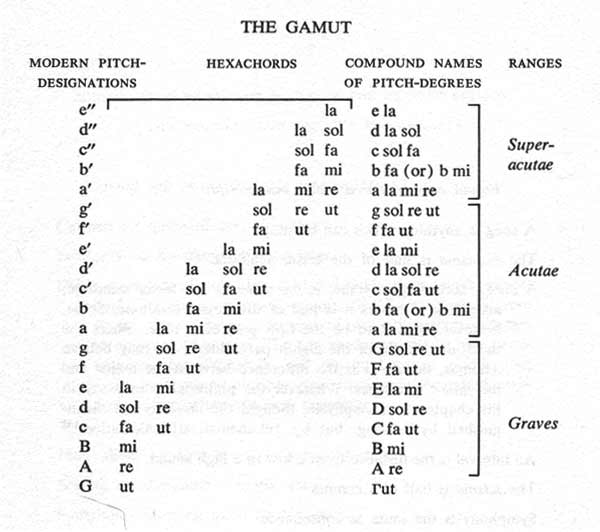

Later theorists’ Gamut Guido’s single hexachord on C was soon expanded to a system of three overlapping hexachords (starting on G, C, and F) that define all of the notes of musica vera (“true music”). Every hexachord, regardless of starting pitch, has an identical structure: ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la, that is, tone - tone - semitone - tone - tone, just like the bottom six notes of a major scale. The “hard hexachord” on G contains the “hard” (hard-edged) or square B (i.e., B-natural). The “soft hexachord” on F contains the “soft” (soft-edged) or round B (i.e., B-flat); The “natural” hexachord on C (Guido’s original) contains neither hard nor soft B. The system of notes included by the three hexachords was called the “gamma ut” or, in the English form, gamut, from the name of its first note, a low capital G written as a Greek gamma. Since it is the beginning of the system, it is also the first note of a hexachord, thus both a Gamma and an “ut.” The notes of the bottom octave of the system were known as the “graves” (the low ones, written as capital letters); the notes of the middle octave were known as the “acutae” (the high ones, written as lower-case letters); the top six notes were known as the“superacutae” or the “geminae” (the very high ones—or the twins, since they were written as double letters). The gamut initially contained 21 notes, up to dd. Later, the third hexachord on G was completed by the addition of a 22nd note, an ee. Having 22 notes in the system may also have reflected the notion of “entirety,” as a parallel to the 22 letters of the Greek and Hebrew alphabets. All notes not included in musica vera were considered to be musica falsa or musica ficta. In the diagram below, the red hexachords are “hard” (include the hard-B), the blue hexachords “soft” (include the soft-B), and the green hexachords “natural” (include neither hard-B nor soft-B).

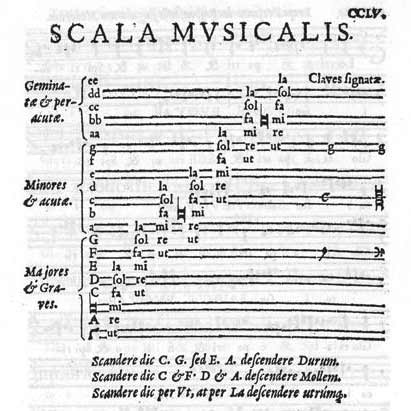

Another way to think about the hexachord system is to consider the note B to have a dual aspect: to be either B-natural or B-flat depending on whether it is in the hexachord starting on F or the hexachord starting on G. In some ways this is easier to visualize: [Diagram taken from Dictionary of Musical Terms by Johannes Tinctoris: An English Translation of TERMINORUM MUSICAE DIFFINITORIUM Together with the Latin Text, Translated and Annotated by Carl Parrish (London: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1963), p. 78] Below is a typical representation of the gamut from the Renaissance (Franz Eler’s Cantica sacra of 1588, p. 255). Note that Eler refers to the three octaves of the gamut as “Majores & Graves” (Capitals/Low), “Minores & acutae” (Lower-case/high), and “Geminatae & peracutae” (Twins/very high). In his scale at the left of the diagram, B is represented as a rounded letter except for the bottom one, which is the square B. When square B is required elsewhere in the gamut he shows it just before the syllable mi. At the bottom are typical 16th-century rules for “mutating” from one hexachord to another: Mutate to a soft hexachord on C and F ascending, on D and A descending. In both cases, start on Ut ascending, on La descending.

|