Socrates' Question

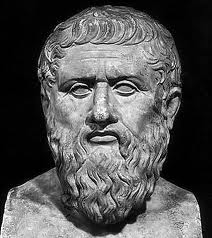

A philosopher named Bernard Williams (1929-2003) once made the following remark about the study of ethics "[i]t is not a trivial question, Socrates said: what we are talking about is how one should live" (Williams, 1985, p. 1). This question of how one should live has sometimes been referred to as "Socrates' Question".

Every culture, every religion, and every community has addressed this question. Every individual human has had to face choices in which they asked themselves, "what's the right thing to do?" The choices we make impact other people, the world, and our own selves. The choices we make express what we think is important; they express some stance on what human life is all about. And the choices we make are a way of living out that astounding human capacity to make good choices in the first place!

The study of ethics dives deeply into what it means to make right choices rather than wrong ones, to live well rather than badly, and which answers to Socrates' question have the strongest support.

Sometimes we will be considering these questions at a rather abstract level, thinking in very general terms about very general features of human life and action. Other times we will be considering these questions on a concrete level, thinking about specific questions having to do with specific issues. And sometimes we will be looking at examples from history, current events, film and television, and other sources that illustrate some of the themes we will be considering.

All of these are important to this study. If we simply consider the abstract questions without looking at how they apply to concrete cases, we will likely get lost in a sea of ideas that end up leaving us cold. On the other hand, if we simply consider concrete cases, we won't be able to adequately consider questions like:

- what are the reasons for people's disagreements, and can they be resolved?

- what assumptions are people making when they express moral beliefs, and are they legitimate?

- what is really valuable and worthwhile in human life, and are there any objective answers to those questions?

And considering how Socrates' question is illustrated by various forms of media can help our minds, as well as our emotions, engage that question in a fresh way.

Whether we realize it or not, our lives are driven by various ideas, values, and assumptions about what matters in human life. We cannot escape Socrates' question. This course is a chance for us to pay close attention to it, in some cases for the first time.

Our Procedure

Each week will consider an important theory of morality as well as a concrete moral issue.

The theory will propose answers to questions like:

- What is morality?

- How does morality figure into a good human life?

- What are our moral obligations?

- Why should we be moral?

This is all part of what we call "normative ethics". That is the field of ethics that considers questions having to do with "norms" (i.e., standards for how one should live and act).

We all live by norms; it would be impossible not to. So "normative ethics" examines these standards to consider how strong they are.

Historically there have been three main approaches to normative ethics. You can try to distinguish them along the following lines:

If we regard human actions as consisting of three parts, then the main difference between these moral theories has to do with which part they believe to be most important when it comes to moral value.

The three parts of human action are:

- The nature and character of the person performing the action.

- The nature of the action itself.

- The consequences of the action.

The three moral theories can be distinguished in this way:

- Virtue ethics focuses on the nature and character of the person performing the action.

- Deontological ethics focuses on the action itself.

- Consequentialism focuses on the consequences of the action.

When moral philosophers examine these theories, they ask certain questions. Among those question are:

- Do these theories give us the right answers to ethical question?

- Do these theories reflect and do justice to our best understanding of what it means to be human?

- Do these theories justify the sense of morality as authoritative or binding (i.e., proscribing how I ought to act regardless of my own interests and desires)?

If you aren't sure how to make sense of these questions yet, that's okay. We will be looking more deeply in them. Part of the way we will do so is by looking at "concrete moral issues".

The "concrete moral issues" will consider attempts to apply the theories to real-life situations.

This is all part of what we call "applied ethics". That is the field of ethics that considers questions having to do with "applications" (i.e., how the theories apply to our lives).

Week 1: Why Ethics Matters

This week we are examining a challenge to and some defenses of the idea that morals express objective standards for how we ought to live. We will also take a look some issues in medical ethics (specifically end-of-life issues). This is intended to give you a sense of why this course, and the theories we will be studying, matter.

Week 2: Making The World a Better Place

In this week we will examine the first of the three major ethical theories, utilitarianism. This is the theory that moral actions are those that lead to the greatest amount of happiness and least amount of suffering for all those affected. We will look at how this theory applies to the questions concerning our moral responsibilities toward animals.

Week 3: Doing One's Duty

This week looks at the second major ethical theory, deontology. This theory argues that we have certain moral duties that we have a responsibility to respect, independently of who we are, our situation, or the consequences of doing so. We will consider whether there are any such moral duties that apply within the context of military action.

Week 4: Being a Good Person

The third major ethical ethical theory, which we will examine in week 4, is virtue ethics. This view holds that the primary ethical concern has to do with the sorts of persons we ought to be, and the character traits (or virtues) needed to be good people. We will consider, by way of example, what virtues are needed to be good stewards of the environment, and the virtues needed to be a good soldier.

Week 5: Looking Deeper into the Ethical Life

In the final week we will focus on gender issues as a way of looking further into the applications, as well as the limitations, of the three traditional ethical theories. Specifically, we will consider whether the female perspective has unique contributions to offer to our understanding of the ethical life regardless of our gender. And we will also consider ethical concerns regarding gender equality.