Moral Absolutes

I have consistently preached that nonviolence demands that the means we use must be as pure as the ends we seek. I have tried to make clear that it is wrong to use immoral means to attain moral ends.

This quote from Martin Luther King's famous "Letter from Birmingham Jail" expresses the idea that actions themselves - in his terms, the "means" - can be good or bad independent of the consequences or "ends", and that good ends do not justify actions that are immoral in themselves. Using "immoral means to attain moral ends" would violate certain moral duties or obligations that apply to us unconditionally.

Do we humans have such unconditional commitments or obligations? For example, if a parent says to her child, "I will be there for you no matter what," does that commitment depend on the whether the good consequences of devoting herself to the child outweigh the bad ones? Or is it the kind of commitment a parent truly assumes no matter what?

The idea that we do have unconditional or absolute commitments, obligations or duties like this is the basis of deontological ethics.

How can I recognize a deontological argument?

Typically an argument that talks about something being good or bad, or right or wrong, regardless of the consequences is appealing to a deontological argument.

The argument will need to somehow show why these things are good or bad, the limits and scope of our obligations, and so forth. But the basic idea is that thinking about the consequences of alternative actions will not settle the issue of right and wrong.

Note something important, however: the deontologist does not claim that consequentialist reasoning is bad, or that we should never think about the consequences when making decisions. We couldn't function otherwise! Rather, the deontologist holds that the basis of moral value is something other than good and bad consequences, and this means that that when pursuing a certain end conflicts with a certain duty, respecting the duty is more important.

To see how this might arise, consider the following illustrations:

Imagine that you are a doctor, and 5 people are brought in, each needing to be treated within the next 20 minutes if their lives are going to be saved. You can treat each one of them in a couple of minutes each, so you know that if you focus on them, you can almost certainly save all 5 lives.

At the exact same time, another person is brought in who also needs to be treated within the next 20 minutes to be saved. However, this treatment will take about 20 minutes. You can save his life, but that will mean that you won't have time to save the life of the 5 other people. On the other hand, if you focus on saving the 5 lives, he will die.

So you have a choice: do I focus on treating the 5, saving them but allowing the 1 to die? Or do I focus on treating the 1, saving him but allowing the 5 to die?

Most people would say that the first choice is obviously better. Why?

Perhaps it is because 5 lives saved and 1 life lost is a better outcome than 1 life saved and 5 lives lost, all other things being equal.

Notice that this is a consequentialist principle, since it is focusing on the outcomes. And a deontological view of morality would certainly agree that this is the right thing to do here.

But let's change the example around a bit, to bring out the differences.

Suppose 5 people are brought in with a life threatening condition, and each requires an immediate transplant of a different organ to survive (one needs a kidney, another needs a lung. etc). If they don't get their transplant soon, they will die, there's not enough time to wait for any donated organs to come in, and the hospital doesn't have anything on hand. So it is inevitable: if the hospital doesn't get 5 healthy replacement organs in the next few hours, all 5 people will die.

It just so happens that Harry has just come in to have a broken arm fixed. The doctor knows of the situation with the 5 people, and after doing some vitals on Harry he concludes that Harry's organs would serve perfectly to save the lives of these 5 people. He wonders whether he should "harvest" Harry's organs or not, and feels hesitant because that would mean killing Harry. But then he remembers that "5 lives saved and 1 life lost is a better outcome than 1 life saved and 5 lives lost."

Would this make it morally right for the doctor to kill one person to save the lives of the 5 others? Most people would say "no." However, if all we consider is which consequence is better overall, then what would stop us from saying "yes"?

If you say something like, "but it's just plain wrong to intentionally kill an innocent person," you're thinking like a deontologist. If you say, "it's not fair to the victim, since he had no say in that" or "we shouldn't simply use people in this way" or "what would happen if everyone did that?" then you're getting closer to the ideas of Immanuel Kant.

As we will see below, when Kant talks about a "duty", he means something that applies to everyone. So it's just not right for me to want everyone else to act in certain way (telling me the truth, not cheating, not stealing from me, not killing me to save others without my consent, etc.) but to think that I should be able to act differently. I shouldn't, according to the deontological view. What's right is right for everyone, and what's wrong is wrong for everyone.

According to the deontological view, moral standards apply in the same way to everyone - not just when they benefit the person, and not simply when they benefit others, but all the time.

The Waiting Room Policy

To get a sense of this, let's take a look at an amusing clip from the TV show Curb Your Enthusiasm. This deals with a relatively minor (yet all-too-familiar) situation, but brings out the deontological idea that when we consider something (like cheating, or a certain waiting room policy) to be right or wrong, it is so regardless of the circumstance. And particularly, regardless of whether abiding by that policy benefits you or not.

Watch:

In this clip, Larry David clearly missed his lesson on deontological ethics. Yet it's not so far-fetched:

How often do we proclaim that something is good and right when we want it to be, but when it is no longer advantageous to consider that good and right, we switch to something else?

Immanuel Kant and other defenders of deontological theory say, that's not what morality is all about.

Do you agree?

What Justifies a Deontological Principle?

It's one thing to claim that something is absolutely wrong or absolutely right. It's another thing to explain why it really is wrong or right.

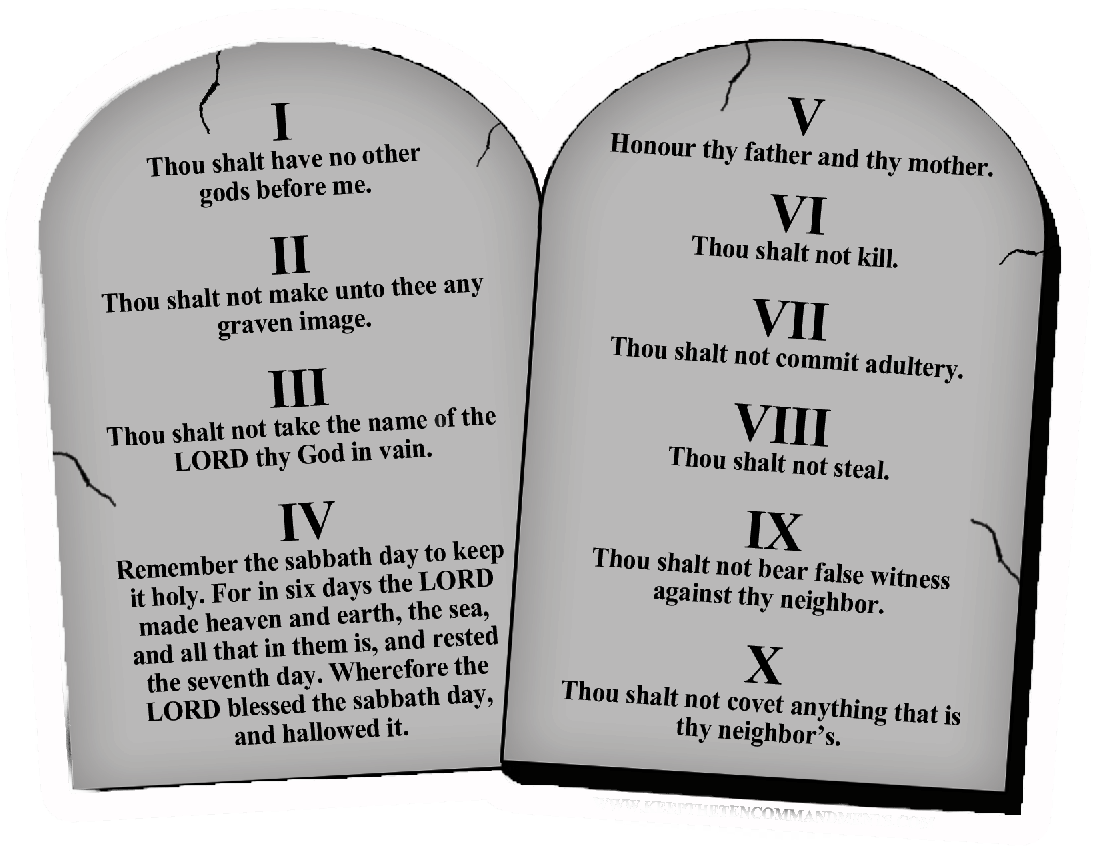

There are many sources of absolute claims, and most of them are part of a code of conduct associated with one's participation in an organization, community, association (such as the military, a family, or a religion).

These are justified by the authority that the religion or organization has over one's conduct. If I regard that authority as absolute, then when the religious text, the parent, the commander, or whoever says "do this" or "don't do that", those commands are ones that I must obey, no matter the circumstance or consequences.

Here's the problem:

Many people today don't recognize anyone or anything as having this kind of absolute authority over everyone, such that we are all morally responsible for upholding its laws and commands. Using religious authorities as an example:

- Some people who are religious believe that the rules set down in the scared texts or by the institution (such as the church) only hold for the most part, and that there's nothing wrong with breaking them every now and then if one thinks one has a good enough reason.

- Those that believe that the religious rules and principles are absolute often don't think that everyone should observe them; they may think they only hold for those who are adherents to the religion.

- Even those who think that the religious rules and principles are true for everyone as an account of how we should live, don't necessarily think that everyone should be expected to recognize or respect them. They might value the freedom of people to make their own decisions about religious matters, and thus not insist that everyone adhere to the principles and rules that derive from religious authority, even if they maintain that it would be good if everyone did.

Most people in the modern world hold to one of these perspectives or something similar. Those that don't are often labeled as "extremists," "intolerant," or "fundamentalists." And while these terms often apply to religious groups, they can apply more broadly when the "authority" in question is a certain charismatic figure, a political ideology, a national identity, and so on.

The problem that arises is this: if the notion of an absolute law or command depends on the notion of an absolute authority, and we reject the notion of an absolute authority (along the lines mentioned above, for instance), then we don't have a way to explain how there can be things that are absolutely right or wrong for everyone.

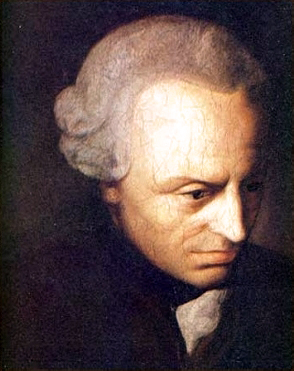

This is where Immanuel Kant came in.

Kant

sought to show how certain moral principles can be true

and authoritative, and recognized as true and

authoritative, by any rational person,

regardless of background, culture, or creed.

Kant

sought to show how certain moral principles can be true

and authoritative, and recognized as true and

authoritative, by any rational person,

regardless of background, culture, or creed.

Immanuel Kant

Kant's Situation:

Kant came out of a culture in which this problem was pressing in a way it had not been for most of human history. Starting in the 1500's, the Scientific Revolution, the emergence of new political structures, and the Protestant Reformation had undermined the dominant authorities up to that time, such as the monarchy and the Catholic Church. These revolutions left in their wake conflicts and wars that threatened the very social fabric of Europe. More specifically for those concerned with moral issues, they brought into question the traditional sources of moral authority. And without the backing of these sources, disagreements, challenges, and disputes became much more substantial, widespread, and even violent.

Some philosophers, such as the Scottish philosopher David Hume, thought that we should abandon the idea that morality has a rational basis, and proposed that we think of it as a certain kind of sentiment or feeling that we have when we regard certain kinds of actions. But many people worried that this would mean we have to do away with the notion of duties altogether.

So Kant tried something else, something that could vindicate the idea of objective and universal moral duty even without the traditional authorities. We will look more closely at his text The Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals in a moment, but here's the basic idea.

Kant's Solution:

Kant came at this problem from two angles. One angle starts with an intuitive idea about what morality is, and tries to spell out and defend that idea in a way that can resolve disagreements about particular cases. The other angle begins with what we all have in common, no matter our religion, culture, or background: that we are rational beings capable of making our own choices. It turns out that these converge on a single idea, what he calls the "Categorical Imperative".

The Idea of Duty

If we back away from all those disagreements and different ideas about what our duties actually are and whom they apply to, what exactly does it mean for something to be a “duty” in the first place?

Well, for one thing, a duty is something I do regardless of my circumstances. Circumstances might include how I feel about doing it, whether it’s convenient for me here and now, and so forth. (When we tell our kids they have to do their chores, we don’t mean “unless you think more happiness will result overall in neglecting your chores to play video games instead." And can you imagine a soldier responding to an order that way? )

If something is a duty for someone, that means that they must do it, regardless of whether it would be convenient or not to, or even it seems like doing something else would be better.

Kant compares it to the laws of nature: sure, it

would be nice if gravity switched off for a while so I

could fly home rather than face the traffic, or so that

I don’t break my neck if I fall off a cliff. But

just because it would be nice doesn't mean it’s

possible – regardless of who I am or how beneficial it

might be to fly, it’s not going to

happen.

According to Kant, that’s how duties work. Obviously we aren’t physically subjected to moral duties in the way we are to the laws of nature, but morally they apply regardless of who I am, what benefits there might be in breaking them, and so forth. Just like everyone is physically going to fall if they jump off a cliff, everyone is morally obligated to do one's duty.

This gives us a clue as to whether a certain action that I’m about to do fulfills my duties or goes against them. If a duty is something that everyone is obligated to do or to avoid doing, we simply ask:

This thing that I'm considering...What if everyone did it?

If that's not something I could will, then we have a problem. For instance, to go back to the example above, if you were a doctor who had a chance to save five lives by killing one person and harvesting his organs, you might think that would be a good thing...but what if everyone did that? What if you, or your child was the one with the broken arm?

If I was a doctor and was morally justified in acting this way, then I could will a world in which another doctor did this to me, or to my child, if the need arose. If I could not will such a world, then I'm saying, "it would be wrong for others to do this...but not for me."

However, according to Kant, if it's wrong for others, then it's wrong for me too; that's what it means for something to be a duty.

Intuitively, the idea behind the notion of "duty" is that if something is morally right for me to do, then it's morally right for others to do as well. Or to put it the other way around, if it's not right for others to do, then it's not right for me to do either. So I ask myself: This thing that I'm considering...What if everyone did it?

The Idea of Autonomy

The other angle starts with something that we all have in common, regardless of our other differences: our capacity for reason and free self-determination, or autonomy. There are other things we have in common, to be sure; Mill and Bentham, for example, thought that we all seek pleasure and the avoidance of pain. Kant agrees (though he would not agree with them that we seek these things above all else). However, we also have this in common with animals.

What animals cannot do, as far as we know, is step back from their desires, impulses, and appetites, and think something along the lines of, "I want to do this, but I really ought to do that," and to act on that thought.

Have you ever been tempted by a desire for something, really tempted, but made a different choice because you tell yourself that you shouldn’t do it?

On the other hand, have you ever been in that situation and felt yourself unable to resist?

If we reflect on those different kinds of experiences, we often find that when we give in to temptation or feel compelled to do something, it’s not really one’s own self determining one’s actions, but some other force, such as one’s desires and appetites, that I haven’t chosen. We feel enslaved by that, whereas when we ourselves are the authors of our own actions - when act on the basis of what we have deliberately chosen to do - we are free.

Kant thinks that this capacity to act autonomously is what gives humans their special dignity, and respecting this dignity will be the basis of an important part of our moral duties as we will see shortly.

But for now, the question is, what does it mean to act freely, rather than governed by what I happen to feel or desire, or by what someone else tells me to do? What is instead determining my actions when I resist that piece of chocolate cake? It’s my reason.

And reason is, fortunately, something that is universal, according to Kant. The reason of an ancient Egyptian is the same as that of a 13th century Mongolian, which is the same as that of a modern American.

So if acting autonomously is acting on the basis of what my own, independent reason decides, and reason is universal, then spelling out what autonomous reason would choose would turn out to be the same thing that any autonomous reason would choose.

So as before, I ask myself, is this something that everyone would choose, if they were acting autonomously?

If I'm merely following my desires, or the dictates of my culture or religion, then there's no guarantee that another person who doesn't share those would choose the same thing. But if I'm choosing for myself on the my own reason, then anyone else who chooses on the basis of their own reason would end up choosing the same thing.

Intuitively, the idea behind the notion of "autonomy" is that of determining one's own actions, rather than having them determined by some other force. To act autonomously is to act on the basis of what my own reason determines, but this will turn out to be the same as what any rational will would determine. So I ask myself: This thing that I'm considering...Is it the sort of thing that everyone could rationally choose?

The Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals

These kinds of ideas were what Kant spelled out in his most famous text on ethics, portions of which you are assigned to read.

Start by reading the marked text on pages 5-6 and 10-12, and come back to this point.

The Good Will

Kant begins the text by having us think intuitively about what it means to call some human quality or human action "good", and proposes that the only thing that is good without qualification is a good will. "The good will," he says,

sparkles like a jewel all by itself, as something that had its full worth in itself.

Think of times when someone - it could be a public

figure or someone you know - did something that at

first glance may seem admirable or noble, but turns out

to have been done on ulterior, self-serving motives.

For instance, think of a politician who serves in a

soup kitchen to get a "photo-op", or a guy

who treats a girl kindly simply because he wants her

wealthy, well-connected father to help him out. Does

that lessen your esteem for what they did? On the other

hand, suppose that someone tries to do something

remarkably courageous, like save someone in danger at

great risk to her own life, but despite her best

efforts she doesn't succeed. Does that lessen our

admiration for the person?

If we said "yes" to the first case but "no" to the second case, that gets to the heart of what Kant is talking about: that it's the goodness and purity of the will that we most admire.

This also gives us a clue about what makes a will good, according to Kant. What is the motive of the good will when it chooses to do something? It’s not “because it will benefit me,” or “because I feel like it,” or “because I’m told to.” All of these presume that if these conditions weren’t there, I wouldn’t do the action (again, think of the opportunistic celebrity or politician). In fact, this goes for any will that is motivated by possible outcomes.

The will that’s truly good, says Kant, is the will that is motivated strictly by the goodness or rightness of the act – someone that would do it regardless of the consequences. It is motivated, in other words, by a respect for duty, or the moral law.

What does it mean to act out of respect for duty, or simply because it's right? It means that the “law” that I’m acting on doesn't depend on any special circumstances, such as how I might feel or whom it might benefit: it is universal.

Moreover, as we said above, if it's right for me, it's right for everyone, and vice versa. So I consider, what if everyone did what I’m proposing to do?

When we take both of these things together, we arrive at the “Supreme Principle of Morality,” which Kant calls the Categorical Imperative:

I ought never to act in such a way that I

couldn’t also will that the maxim on which I act should be a universal law.

Treating People With Respect

Kant expressed this "Categorical Imperative" in several different ways or "formulas". The one we examined above is often called the "Formula of the Universal Law", because it has this notion of the universal law at its center.

There is another formulation that many people find a bit easier to understand and apply, sometimes called the Formula of Humanity, and it goes like this:

Act in such a way as to treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of anyone else, always as an end and never merely as a means.

Read the short section marked out on page 28, and come back here.

What is it to "treat humanity...as an end"?

We need to first clarify two key terms here, "humanity" and "end" (or as we sometimes see it expressed, "end-in-itself"). It turns out that they are pretty closely related.

What does Kant mean by "humanity"?

"Humanity" can mean many different things (like having a certain DNA), but here Kant is referring to something very specific: our capacity to set our own ends and act on them, rather than having our ends and purposes determined by some other person or force. We spoke of this above as our "autonomy". This is what distinguishes us humans from inanimate objects, plants, and other animals, and so it marks out what is special or distinctive about our "humanity".

So in Kant's system, our "humanity" is our capacity to rationally and autonomously set and pursue our own ends. So far so good.

What does it mean to treat something as an end-in-itself?

We can think of an "end" as the counterpart to being a "mere means".

First, think of what it is to call something an "instrument" or a "tool". Let's say, a hammer. Does it have any goals or purposes of its own? No, of course not. Its whole purpose is to be at my disposal for driving in nails or whatever I want it to do; a hammer is merely a means to my ends. So treating it as a "hammer" just is to...use it as a means for whatever I need. In Kantian terminology, it isn't an end-in-itself; a hammer's "end" (or purpose) is whatever I happen to need it for, nothing more, nothing less. Not so complicated. However....

If something is an end-in-itself, it means that it has value beyond whatever purposes another happens to need it for.

To treat something as an end-in-itself means that my decisions, especially those that concern the thing, respect this value.

Humanity As An End-In-Itself

According to Kant: "humanity", as we defined it above, is not merely a tool to be used, or a means to someone else's ends. It exists as an end-in-itself, and should be treated as such. Why is this?

The basic reason is that “humanity”, as we saw above, is the capacity to set and pursue one’s own ends, as opposed to a tool whose use is determined by the person using it, or a plant or animal whose behavior is determined by nature. The capacity to act freely is what makes us more than mere instruments or slaves to desire (our own, or anyone else's). It is what gives human life its special dignity.

But why should we respect that dignity in the way we treat other people?

First, let's think about the "Golden Rule: do unto others as you would have them do unto you." How do I expect people to treat me? Think especially of a choice you have made that someone else doesn’t necessarily agree with.

It might be something as simple as choosing the get an anchovy pizza when your friend thinks that’s disgusting. Or it might be something like choosing to go back to college to strive for a better job, when your boss thinks that you should be grinding it out in the job that you have (thus benefiting him). Perhaps your parents disapprove of the person you have chosen to be in a relationship with, or some of your friends don’t like the way you choose to dress, or your aunt disapproves of how you’ve chosen to discipline your children. Or perhaps you live in a community in which most people are part of a certain religion, but you are part of a different religion (or no religion at all). Perhaps you want to purchase the car that’s best for you and your family, but the salesman would rather coerce you into purchasing the car that would bring him the most profit.

In such cases, we generally would say, "I think that people ought to respect my own choices. And I don't mean, 'if they feel like it,' or 'if it benefits them'; I mean, 'if I make a choice about how I’m going to live my life, people ought to respect that, because it’s a choice I’ve thoughtfully and deliberately made myself.'"

Why should we think that? How could I possibly expect someone to respect and value what I've chosen if it's not something they would choose, or even something they agree with?

It would only make sense if I assumed that the very capacity to rationally and deliberately set and pursue ends was itself of fundamental value, and gave value to those ends.

This capacity to rationally and deliberately set and pursue ends is what we just defined as “humanity.” And so, when we reflect on how we expect others to treat us, we find that we all seem to acknowledge that “humanity” – the capacity to rationally set and pursue ends – is itself valuable and worthy of respect, regardless of whether it serves someone else's purposes. It is an end-in-itself.

Reflecting on how others should treat me leads to a general principle about how people in general should treat each other. This means that I have to likewise acknowledge the value of the choices that other people make, even if I disagree with them. Why? Because like me, they are also thinking, choosing beings.

The bottom line is this:

We all recognize something important and valuable about the capacity we humans have to rationally and autonomously set ends and pursue them. But if that's going to have any sense to it, if it's going to be more than just hot air, then it applies anywhere we find this capacity, no matter the person's race, color, religion, gender, social status, history, prior decisions, or any other detail about their lives.

To tie things up, let's get back to tools.

Back to the Tools

Recall that when we treat something (like a hammer) as a tool or a "mere means", we are saying that it doesn't have any end or purpose in itself; rather, its ends and purposes are what I, the user, give it, and it's perfectly appropriate for me to use it accordingly. When I treat something as a tool, I am treating it merely as a means to my ends.

But now we see that humans are different: we each have a capacity to set our own ends and determine our own purpose, and we recognize that as worthy of respect.

My purpose isn't to simply serve another will; I have values and goals of my own, and I expect others to respect that. But if I expect that of others, others can legitimately expect the same of me.

Kant himself puts it this way:

I maintain that man—and in general every rational being—exists as an end in himself and not merely as a means to be used by this or that will at its discretion. Whenever he acts in ways directed towards himself or towards other rational beings, a person serves as a means to whatever end his action aims at; but he must always be regarded as also an end.

This means that in everything I do, I should be acknowledging and respecting this fact about each person's humanity. In other words, in each decision I make, I should always be respecting the value of each person's humanity, and never treat people simply as "tools" to be used.

Two Clarifications

There are two ways in which people often misunderstand these ideas.

Does this mean that we have to accept whatever people choose, or that we can’t challenge or disagree with it?

No, not at all.

First, what we are obligated to respect is people’s humanity, which in this case is their capacity to rationally and deliberately set and pursue their own ends. When someone is acting in ways that clearly seem to be irrational, or they are being driven by mere desire or impulse, it’s not clear that we have an obligation to respect their choices. For example, if someone is clearly driven by an addiction to make certain choices, it’s not clear that we have an obligation to respect those choices.

Second, there are cases in which the choices that people make infringe on the capacity of others (such as oneself) to also set and pursue their own ends. For example, if Mary has decided that she really wants a promotion at work, and she spreads lies about her colleagues that also want that promotion, I certainly have no obligation to respect her choice to spread those lies since they clearly inhibit the efforts of her colleagues to pursue their ends.

But third, even when it seems that another person has made a reasoned, deliberate choice, and one that respects others’ capacity to do the same, it doesn’t mean we have to accept what they’ve chosen. In fact, we can often show great respect toward people by offering them reasons why we think that what they are doing is wrong. When we offer people reasons in this way, we are in effect saying, “I think you are a reasonable person, someone that can make rational choices about how to act. I don’t think your current choices are the best, and I’m going to try to explain why.” This attitude is captured by the famous quotation, "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it." In other words, to respect someone does not mean we have to agree with them or approve of what they say. (And if I’m going to be consistent, I have to allow that when another person disagrees with or disapproves of what I have chosen, that’s not necessarily a sign of disrespect.)

Does Kant say that we should never use people, period?

No.

For one thing, that would be impossible, since we depend on other people, and others depend on us; thus, we "use" people all the time! (You are "using" me, your professor, to get an education!)

For another thing, many people freely choose to be “used”! Again, I have chosen to put myself at your service in your aspiration to get an education. People choose to put themselves at the service of others in a host of ways, from donating to charities, developing useful software, building roads, helping to care for and educate children, defending citizens their own or of other countries against threats, helping people figure out the details of their medical plan, and on and on.

The basic idea is this: when I use people (or when others are using me), are we acknowledging and respecting the fact that we are all people who can think for ourselves and make our own decisions?

General principles like these can sound well and good, but what do they mean when we try to put them into practice? That's what we will consider next.

Applying the Categorical Imperative

Let’s rehearse the main points so far:

- A deontological theory of morality focuses on the moral value of actions themselves, independent of the character of the person performing those actions or the results of those actions.

- We have a duty to do those actions that are good in themselves, and a duty not to do those that are bad in themselves, regardless of whether we want to act otherwise or think that acting otherwise will bring better results.

- Kant maintains that we can sum up all duties in terms of a single, overriding duty: the Categorical Imperative. “Categorical” means “applying no matter what”; ‘Imperative” means “something that must be done.” So the Categorical Imperative is something that must be done, no matter what.

- The Categorical Imperative can be put into

words in two different ways.

- In one formulation, it says that “I ought only to act on those maxims that I could will to be universal law.” We often call this the Formula of Universal Law.

- In another formulation, it says, “So act that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means.” We often call this the Formula of Humanity.

This can all sound quite abstract, and it's often hard to see how this applies to our lives and our decisions. Kant provides us with four examples, and shows how the Formula of the Universal Law and the Formula of Humanity apply to each.

The examples are:

- committing suicide

- making a false promise

- cultivating one's talents

- acting benevolently toward others

You may notice two things about this list:

- Two of these have to do with how we act toward other people (2 and 4), and two have to do with how we act toward ourselves (1 and 3).

- Two of these concern actions we have a duty to do (3 and 4), and two concern actions we have a duty to not do (1 and 2).

So the list covers a huge range of actions that have moral significance.

We will look at how to a apply a "test" to see whether a maxim is consistent with the Categorical Imperative, but first here are some rules of thumb:

- When considering whether an action is a negative duty (something I must not do), we apply the Categorical Imperative test to the maxim of the action, and if it fails the test, I know that the action is morally prohibited (like 1 and 2).

- When considering whether an action is a positive duty (something I must do), I consider a maxim in which I don't do it, and see if that passes the test. If it does not, then I know the action is morally required (like 3 and 4).

The Categorical Imperative Test

Here's the way we test to see whether an action is morally required or prohibited. Remember that the imperative is that I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law:

- Formulate the maxim that you’re considering acting on (what you intend to do, and why you intend to do it).

- Formulate the corresponding universal law.

- Consider the world in which this maxim was universalized into a law (i.e., imagine a world in which everyone supports and acts on your maxim).

- Figure out if there’s a contradiction in this world (i.e., could the goal of my action be achieved?).

- If the answer to (4) is no (the goal could be achieved), then the maxim is universalizable, and the action is morally acceptable.

- If yes (the goal could not be achieved), then the maxim is not universalizable, and the action is immoral.

Let's look at Kant's four cases and see this test at work.

Go ahead and read the marked text on pages 24-25, and come back to this point.

Test Case 1: Suicide

Think back to week 1 and the problem of physician-assisted suicide that we considered. Many people described it as the person choosing to do what's best for himself or herself.

Can a maxim of suicide pass the Categorical Imperative test?

- Maxim:“Because I want my life to be the best it can be, and I foresee that my life holds the prospect of great pain and suffering, I am going to end my life.”

- Universal Law:Whenever we foresee that someone's life holds the prospect of great pain and suffering, we end that life.

- The World: We are promoting and enhancing life, and destroying it at the same time.

- Contradiction? Yes: You can't promote and enhance something while destroying it at the same time.

This is a challenging argument, but the basic idea is this: a maxim of suicide is rooted in care and concern for oneself (we don't want to suffer). Kant thinks that there's a deep problem with the idea that we should express care and concern for something by intentionally destroying it.

Another way of looking at it is to imagine a world in which anytime someone is suffering or in pain, we end that person's life. It's not hard to imagine that such a world would be a dreadful place: we would constantly live in fear of losing our lives anytime we were in pain. If I can't will that others go around killing those who are suffering, then it's inconsistent for me to will that I kill someone because that person (who happens to be me) is suffering.

Test Case 2: False Promises

I am considering whether it would be wrong to borrow money from a person and promise to pay it back, but not actually do so.

- Maxim: “When I believe myself short of money, I will borrow money and promise to pay it back, even though I know that this will never be done.”

- Universal Law: Anytime someone can get quick money by making a false promise she will do so.

- The World: In such a world, there would be no such thing as promises.

- Contradiction? Yes: if (2) and (3) are true, you won’t be able to do (1).

The key here is step 3: if we all made false promises, no one would believe anyone's promises, including mine! But I need people to believe my promises; otherwise, I won't be able to get the money that I'm trying to get by making that promise. So essentially I'm saying, "I want to make a false promise, but I wouldn't want others to make a false promise."

If we couldn't will something to be universal law, then essentially we're saying, "well, I don't think it would be good if everyone did this, but I'm going to do it." What makes me special, such that I don't have to respect the same principles that I want everyone else to respect?

Remember Kant's claim that the "Good Will" has the greatest value, and it's the will that acts simply because something is the right thing to do, without ulterior motives such as self-interest. Clearly a person making a false promise is not expressing a good will in this way.

Let's look at the third case now.

Test Case 3: Cultivating One’s Talents

Do I have a duty to try to develop myself, to spend my time on things that involve using my higher human faculties, to be "the best that I can be"? Or do I have a moral right to do whatever I want with my life, even if that means whiling away and wasting my time in meaningless or trivial pursuits, superficial amusements and pleasures, etc.?

Remember that if we want to consider whether we have a positive duty to cultivate our talents, we should look at the corresponding negative maxim - the maxim associated with not cultivating one's talents. If that fails the test, then it goes against duty to not cultivate one's talents...which is to say we have a positive duty to do that.

- Maxim: I'm going to neglect my natural gifts and devote my life merely to enjoyment.

- Universal Law: Anytime someone can find enjoyment she does so, even if it means neglecting the development of one’s natural gifts.

- The World: My natural gifts serve me and allow me to obtain my purposes. So I wouldn’t be able to attain my purposes (e.g., enjoyment).

- Contradiction? Yes: Without cultivated talents I cannot attain what I will, so I cannot will a world in which I am not able to attain what I will.

Test Case 4: Beneficence

Again, to see if we have a duty to be generous and helpful to others, we consider the opposite maxim and see if it passes or fails the test. If it fails, it means I cannot not help others, which is to say I have a positive duty to help others.

So can I adopt a maxim in which I simply keep for myself whatever extra money, time, and resources that I have? Live and let live, to each his own, right?

- Maxim: I shall not contribute to the welfare or assistance in need of others.

- Universal Law: No one contributes to the welfare or assistance in need of others.

- The World: I often need others to contribute to my welfare and assist me when I’m in need. But I would not be able to obtain that.

- Contradiction? Yes: Without help from others I cannot attain what I will, so I cannot will that I not be able to attain what I will.

Applying the Formula of Humanity

Some people have criticized Kant's Formula of the Universal law for seeming contrived and unpersuasive, at least on some of the issues he applies it to, and find the Formula of Humanity clearer and more plausible as an account of our duties.

Remember that the Formula of Humanity states:

“So act that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means.”

Go ahead and read the marked text on pages 29-30, and come back to this point.

The basic question when applying the Formula of Humanity is, does my action respect the person's capacity as an autonomous rational agent?

We can think of this as having two dimensions to it, a negative and a positive dimension.

The negative dimension would be: never merely use other people. How can we do this? By asking ourselves, could the other person autonomously (i.e., rationally) accept the maxim of my action? Could they say, "okay, I accept that." Am I playing fairly, so to speak?

We can see how making a false promise would violate this. Could someone rationally agree to this? Of course not! By making a false promise, I'm making it impossible for them to exercise their autonomy. In other words, by giving them false information, I'm trying to manipulate them into making a decision that they might not otherwise make if they knew the truth. More generally,

anytime we act people in ways that involve force, coercion, deception, and manipulation, we are implying that the other person's own choices don't matter, only mine do, and thus I can use them as a mere means to my ends.

The positive dimension goes beyond simply not using people without their rational consent. Rather, we also respect human dignity and autonomy by actively trying to promote other people’s ends as far as possible.

By practicing beneficence, for example, we're saying to the other person:

"You have dignity, and your ends are valuable, so I'm going to do what I can to try to help you attain them."

In other words, respecting other people is more than a matter of making sure that my ends don't interfere with their ends; rather, it's also a matter of trying to make their ends my own ends as well, as far as can be.

What about the duties to oneself, the duty not to commit suicide and the duty to develop ones talents? How does Kant think the Formula of Humanity applies to those?

As for suicide, by destroying myself when life becomes difficult, I am regarding my person, my rational autonomy, merely as a means to maintaining a comfortable life. In other words, I'm regarding the value of my capacity for autonomous rational choice as reducible to a tool for attaining pleasure and avoiding pain. As we have seen, Kant thinks that this is an affront to our dignity. It doesn't matter whether it's my own pleasure and pain at stake, or someone else's; either way, I'm being reduced to a tool.

Something similar goes for cultivating one's talents. As a result of our humanity, we humans are capable of far more than trivial amusements or base pleasures. Cultivating one's talents is a way of participating in these possibilities. So by wasting oneself and refusing to develop oneself, one fails to respect this humanity of ours.

Problem Cases

As with utilitarianism, Kant's moral theory may sound plausible in theory and when applied to certain cases, but the real test comes when we consider what it says about hard cases. Let's take a straightforward case: lying.

Lying, like making a false promise, involves a maxim that cannot be universalized, since if it were no one would trust anyone else. And if no one trusted anyone else, then I would not be able to achieve what I'm trying to achieve by lying. So it fails the "universalizability" test. It also involves trying to manipulate and coerce someone into making a choice they otherwise might not make. In both of these ways, then, it conflicts with the Categorical Imperative, and is thus immoral, according to the Kantian view.

Naturally this seems right, for the most part: lying is certainly one of those things we have been taught was immoral since our earliest days, and it has been regarded as immoral by virtually all cultures. But are there cases when it seems like lying would be the right thing to do?

We can imagine everyday cases in which a "white lie" might avoid hurting someone's feelings, and there doesn't seem to be any real harm.

"Ummm....y-yes?"

More serious cases arise, however, when lying would prevent some great evil or injustice from occurring. For example, in the opening scene of Quentin Tarantino's 2009 film Inglorious Basterds, a Nazi officer hunting down Jews visits a French farmhouse where he suspects - correctly - that some Jews may be hiding. He asks the farmer whether he is hiding any Jews in his house. The farmer knows that if he tells the truth, the Jews will either be killed on the spot or taken to a Nazi death camp. What should he do?

Most people immediately say of course he should lie (for simplicity's sake, let's ignore the detail about his family being left alone if he tells the truth). If he tells the truth, these people who have entrusted him with their lives would suffer and die. Besides, the other man is a brutal murderer; he doesn’t deserve to be told the truth!

Not so fast, answers Kant. In a short article provocatively entitled, “On the Supposed Right to Lie from Altruistic Motives,” he considers a very similar sort of situation, and steadfastly maintains that the authority and dignity of the moral law does not change, even in cases such as these. If I make an exception here, what’s to prevent me from making an exception in some other situation in which lying would benefit me?

Nor, we should add, does a person’s human dignity depend on who they are or what they choose. Remember that the notion of human dignity was based in our autonomous rationality - our capacity to freely set and pursue our own ends - and a person does not lose this capacity when they make immoral choices. Thus we still have a duty to treat any person - even brutal Nazi officer - as an end-in-itself, which means we cannot lie.

What about the victims? If he tells the truth to the Nazi officer, isn’t he responsible for their suffering and death?

No, Kant says: the officer is the one responsible. By telling him the truth, the farmer would be giving him the chance to make the right decisions for himself, respecting his autonomy. If the officer makes the wrong choice, that’s an unfortunate tragedy, but the farmer is not responsible for what the officer does; he’s responsible for what he does. That’s the essence of human autonomy.

Convinced? Many people aren’t, even those who otherwise defend Kant’s moral philosophy. What should we say in response to such a case? Is there a way the farmer could have protected the Jews under his care without violating his moral duty? Do we have to bite the bullet and say that even in this case lying is wrong, however tragic the outcome? Is Kant’s philosophy flawed in some way? Or is there some other response that we should take to this kind of dilemma?

Similar concerns can be raised about lots of cases in which breaking the moral law would seem to do great good or prevent great evil. One area in which people have debated over these questions for centuries is the context of war. This is what we will turn to next.

Going Deeper

Kant's ideas are notoriously difficult, and if you still don't quite get it, join the club. Sometimes it means reading multiple explanations of what trying to say. One of the best explanations of the Formula of Humanity is found in Onora O'Neill's (1993) article, "A Simplified Account of Kant’s Ethics." O'Neill is one of the world's most prominent Kant scholars, and in this article she explains how the Categorical Imperative can apply to the problem of world hunger, which can then serve as a model for applying it to other moral problems as well.

For a summary of Kant's Groundwork that explains portion's of the text not covered by the required readings, and see Geoffrey Sayre-McCord's (2000) "Kant's Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals. A very brief selective summary of sections I and II.", which can be accessed here.

Multimedia

The philosopher David Velleman, another respected scholar of Kant's ethics, has a series of short video lectures that are clear and accessible, and which you can access here.

Web Resources

- Kant on the Web.: http://staffweb.hkbu.edu.hk/ppp/Kant.html

- Kant Links: http://comp.uark.edu/~rlee/semiau96/kantlink.html

- Kant overview: http://philosophypages.com/ph/kant.htm

.jpeg)