LEARNING MORE ABOUT THE MUSIC WE SING

|

Lesson 10, for April 22

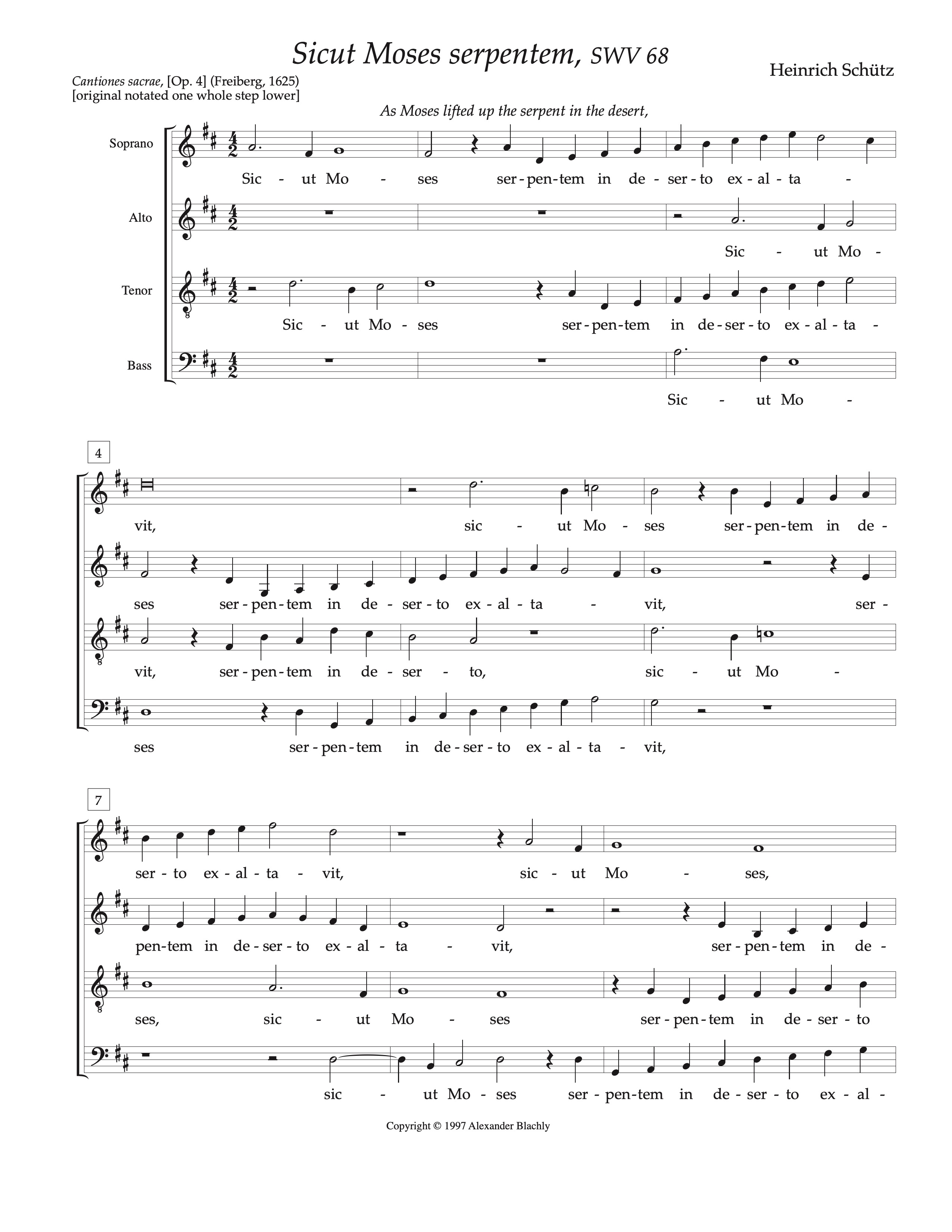

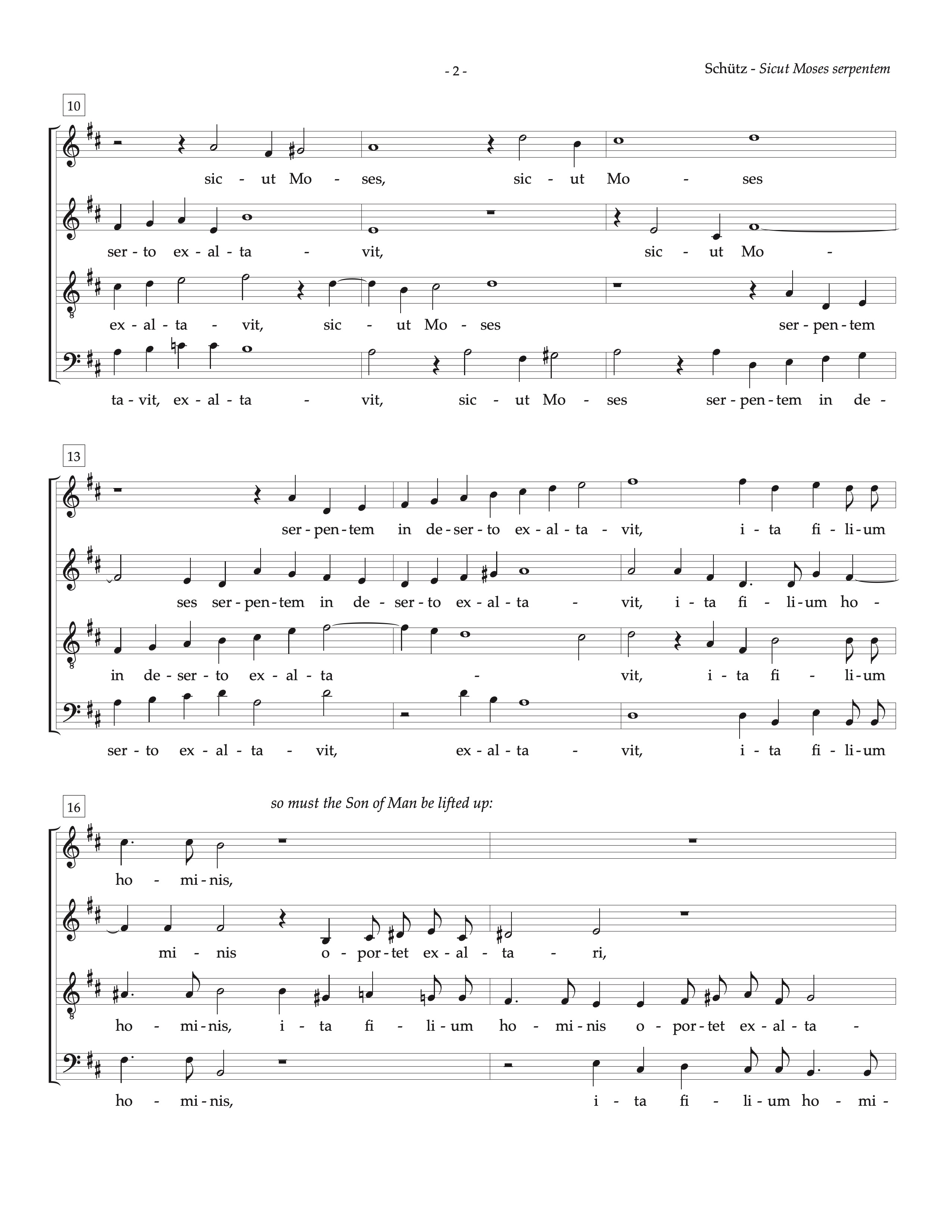

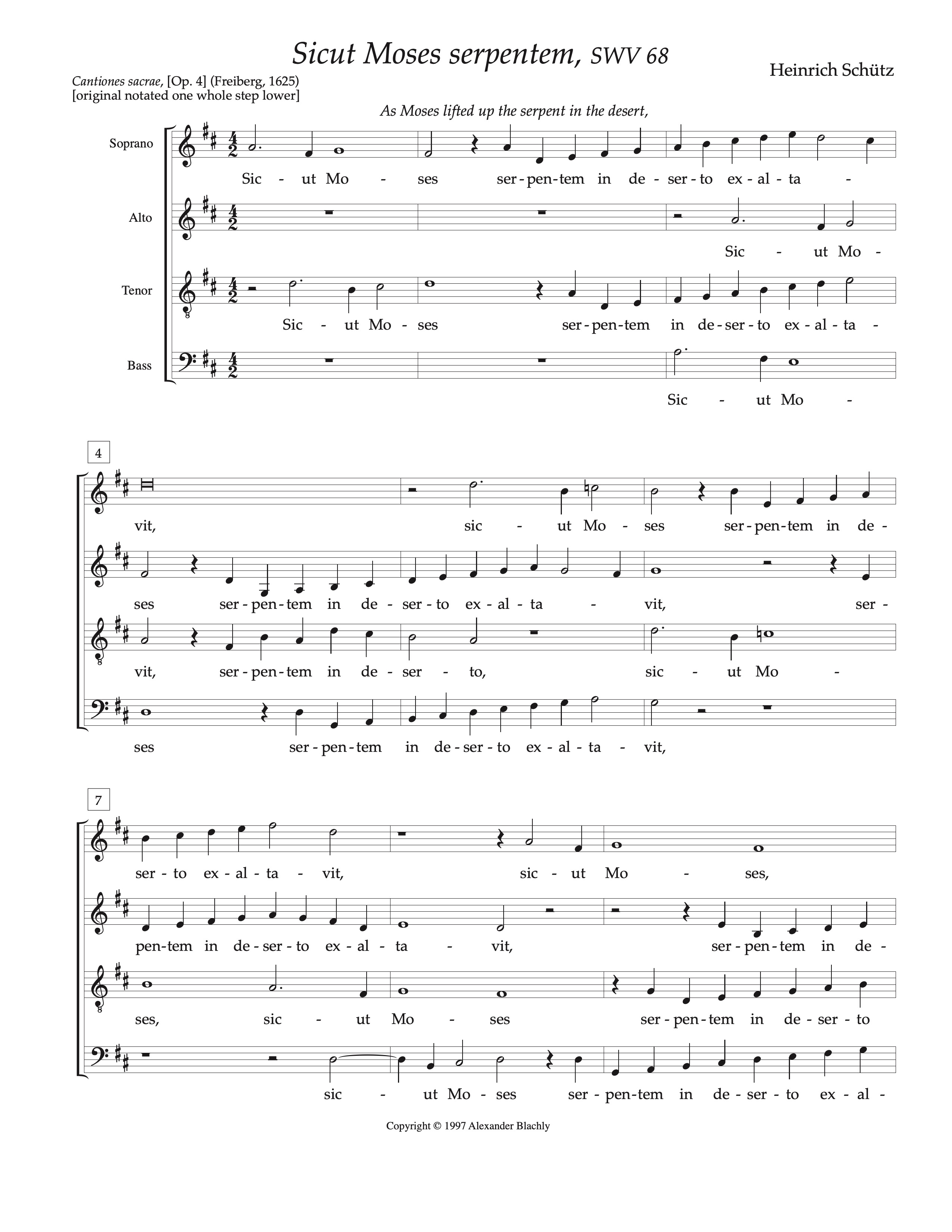

Like Purcell, Heinrich Schütz was a product of the seventeenth century, and his Sicut Moses serpentem is a case study in musical rhetoric. Clearly, the words “lifted up the serpent in the desert” are illustrated by the rising motif sung to these words in all voices. Is it possible also that the very first word, which begins with a somewhat hissing “s,” represents the hissing of a snake? The opening passage ends with the sopranos singing their highest note yet on the word “exaltavit” (mm. 14-15).

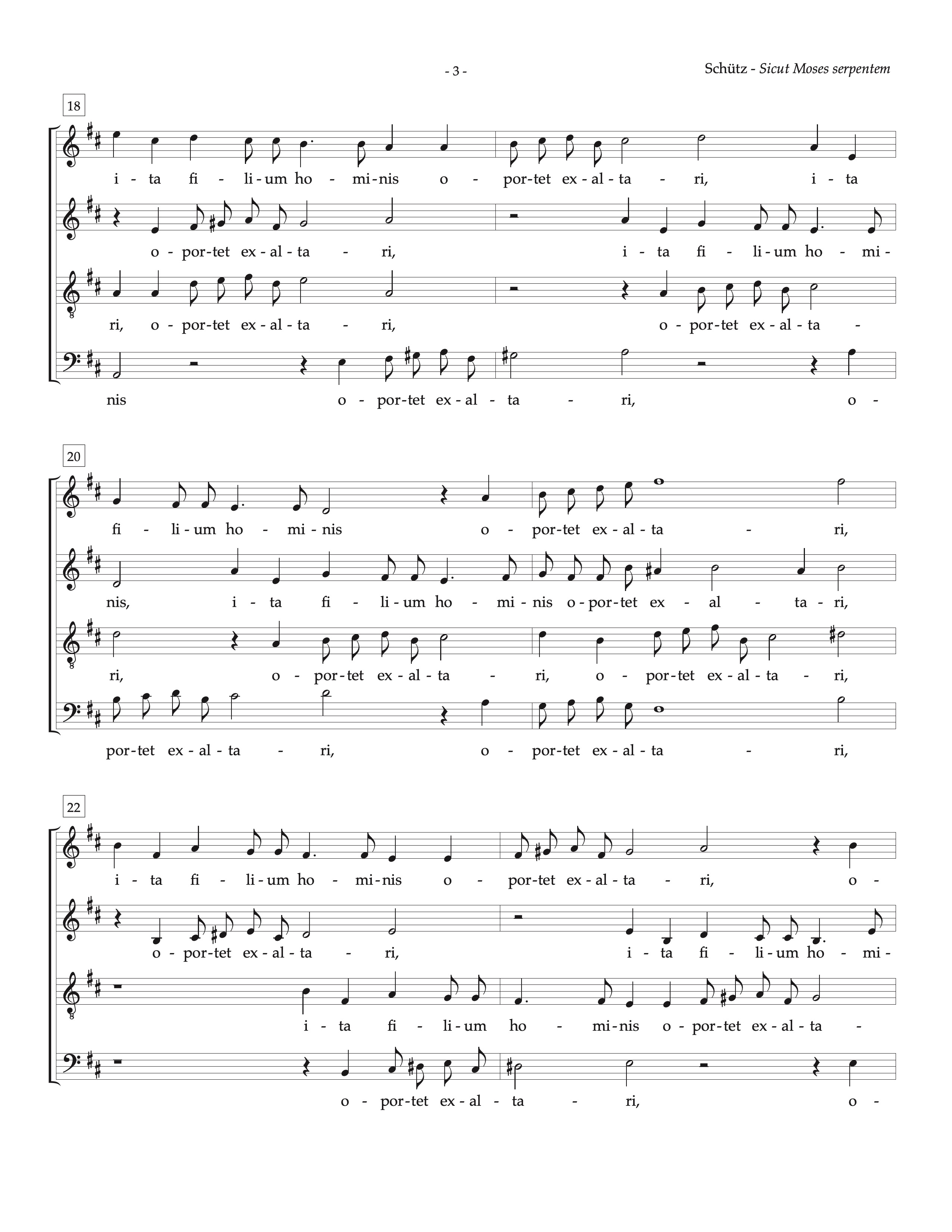

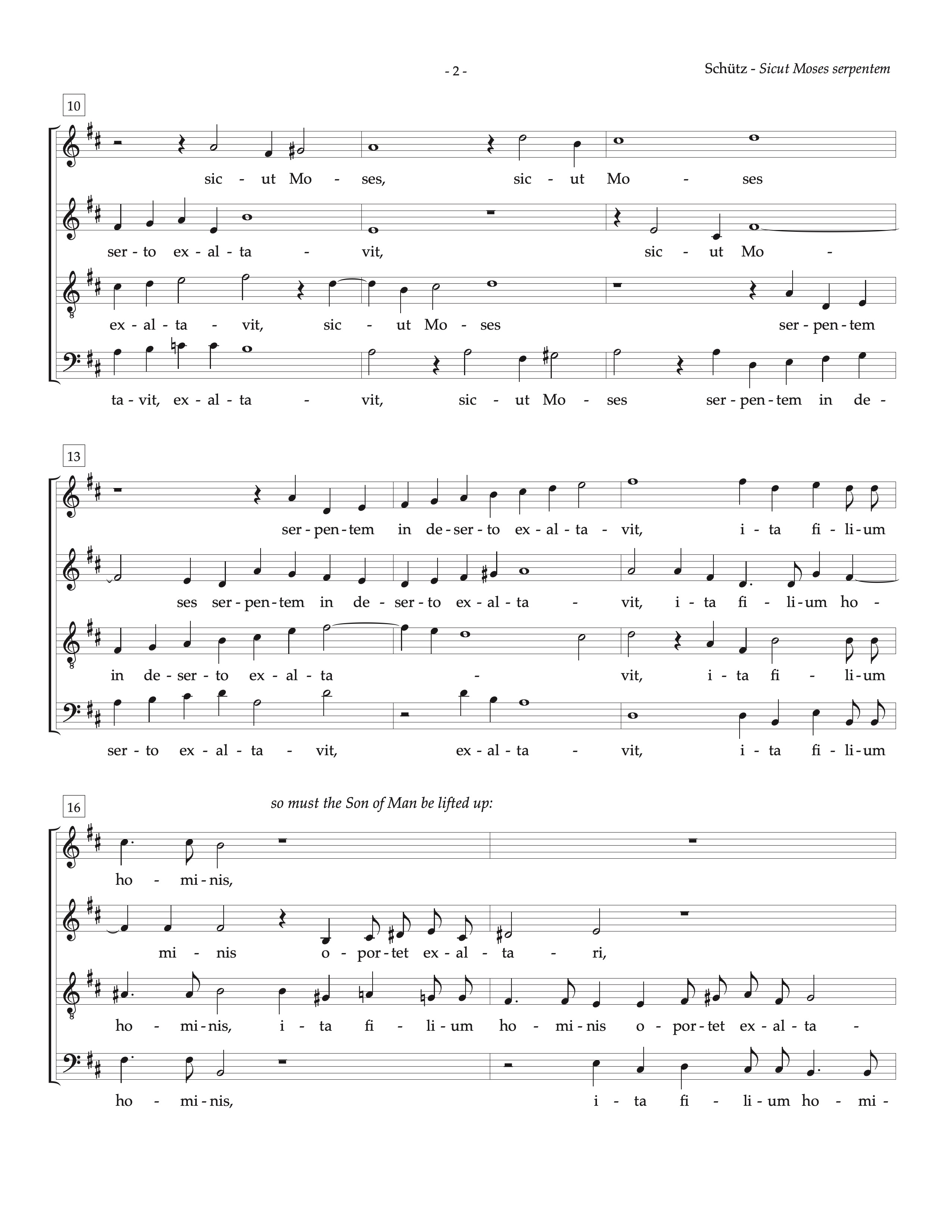

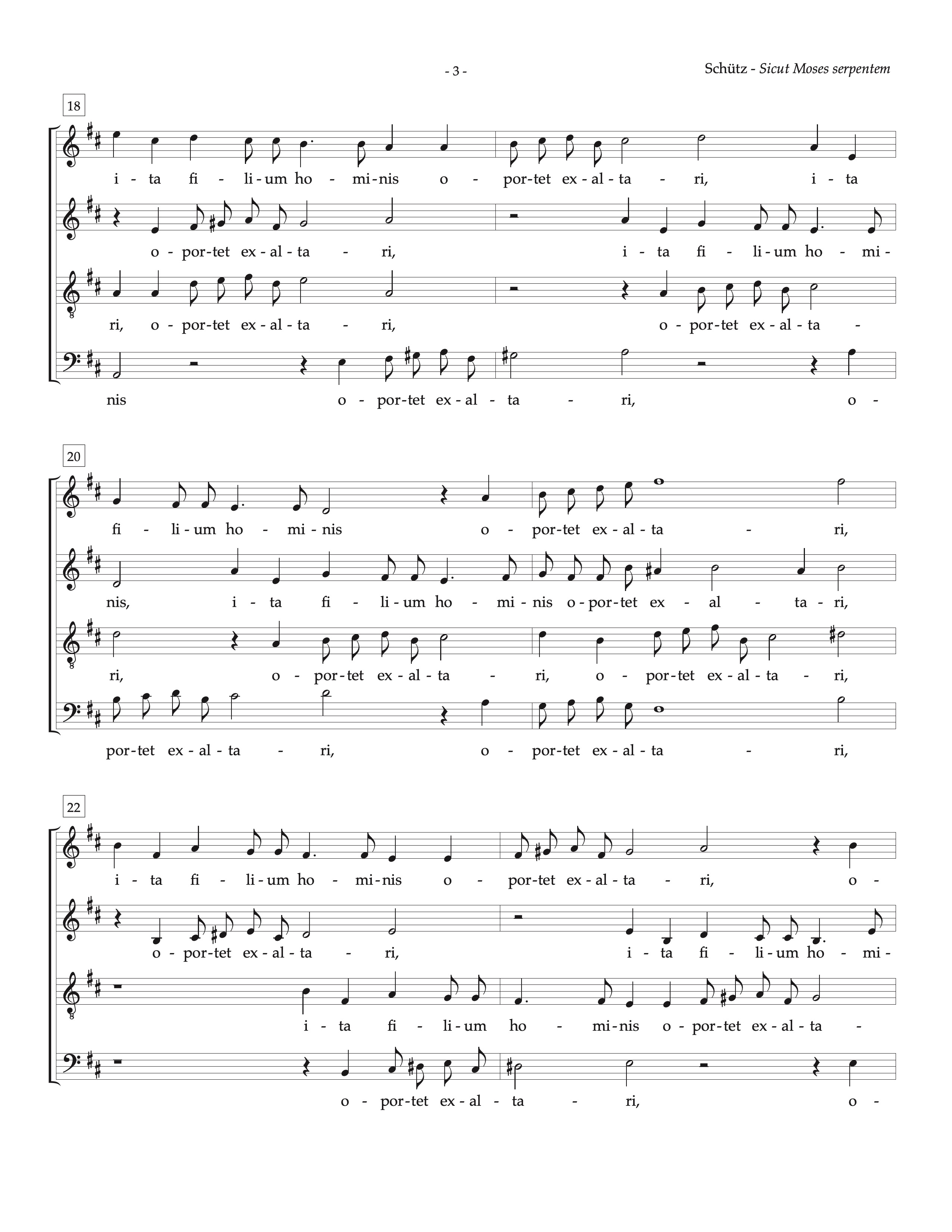

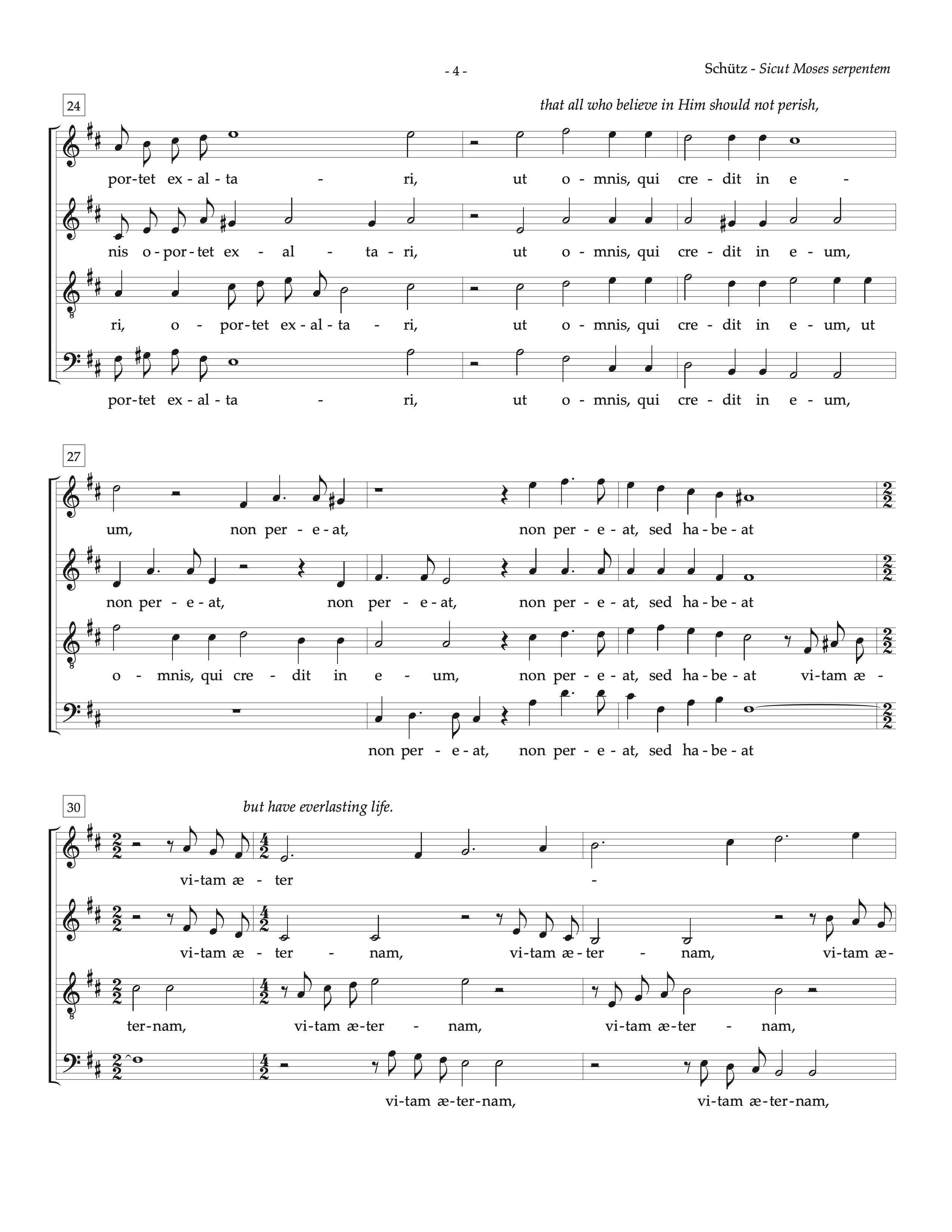

The words “ita filium hominis oportet exaltari” (“so must the Son of Man be lifted up”) have overlapping entries in the four voices that continue for some time before another cadence on a high soprano note in m.24 on the word “exaltari.” It almost feels like a crowd of people saying the “ita filium hominis” words over and over in a jumble of exclamations.

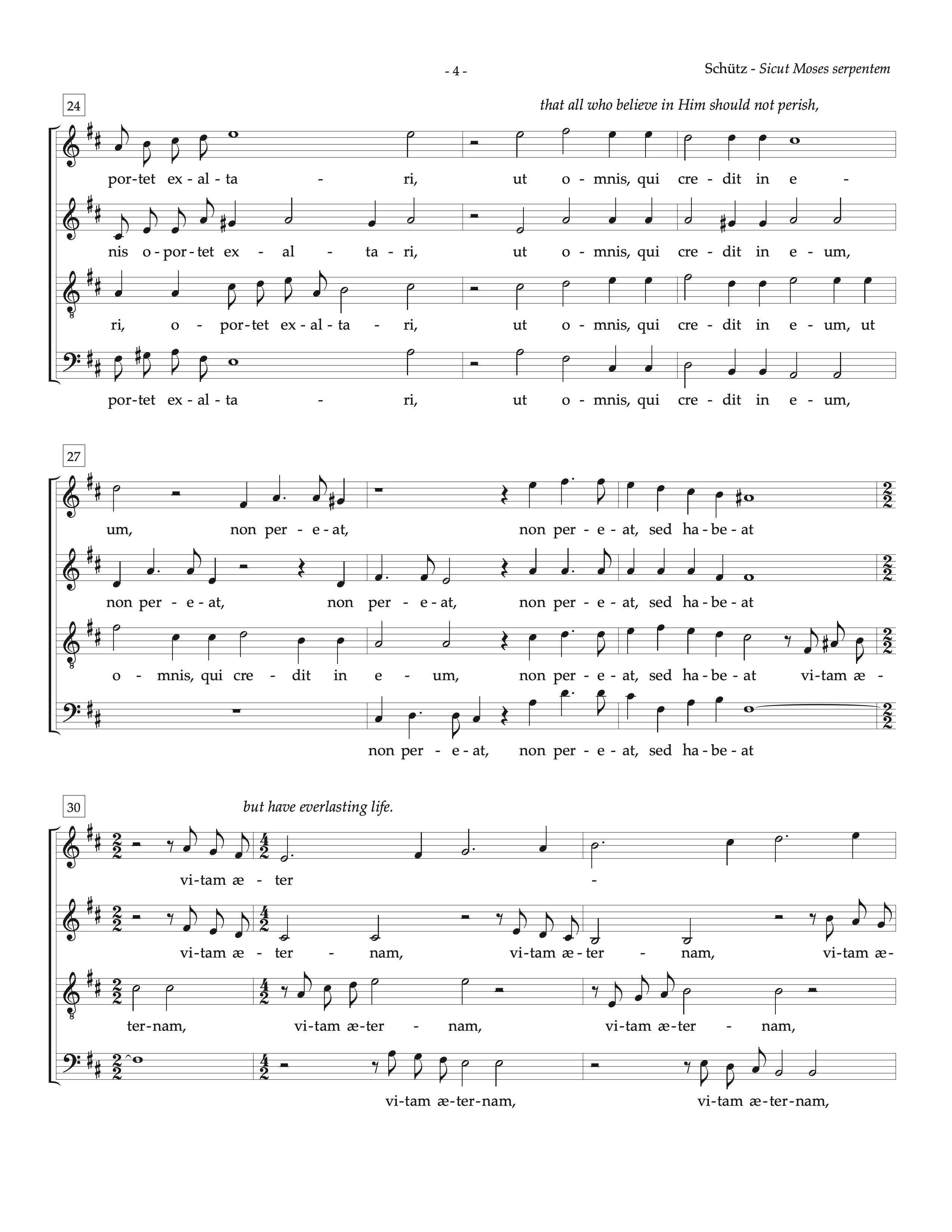

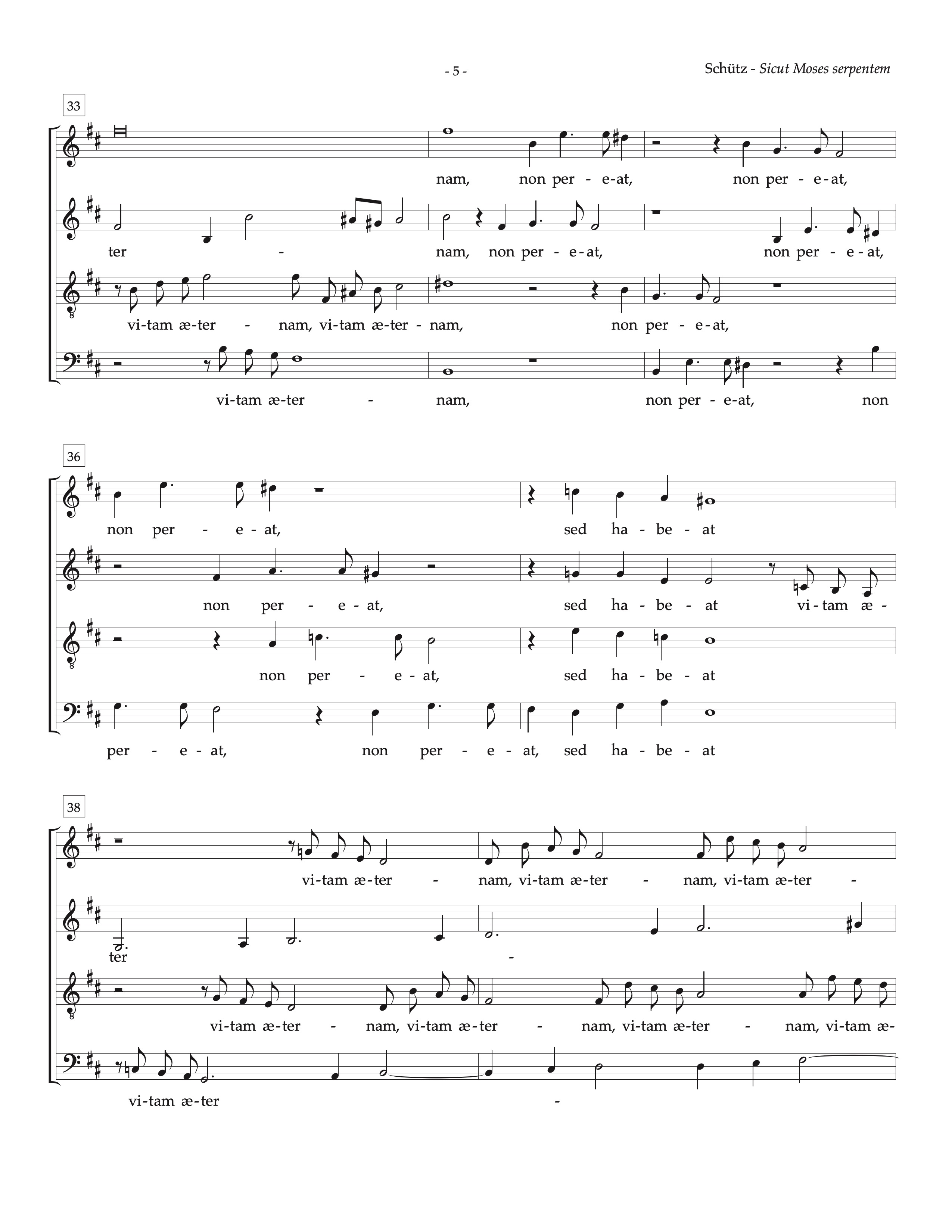

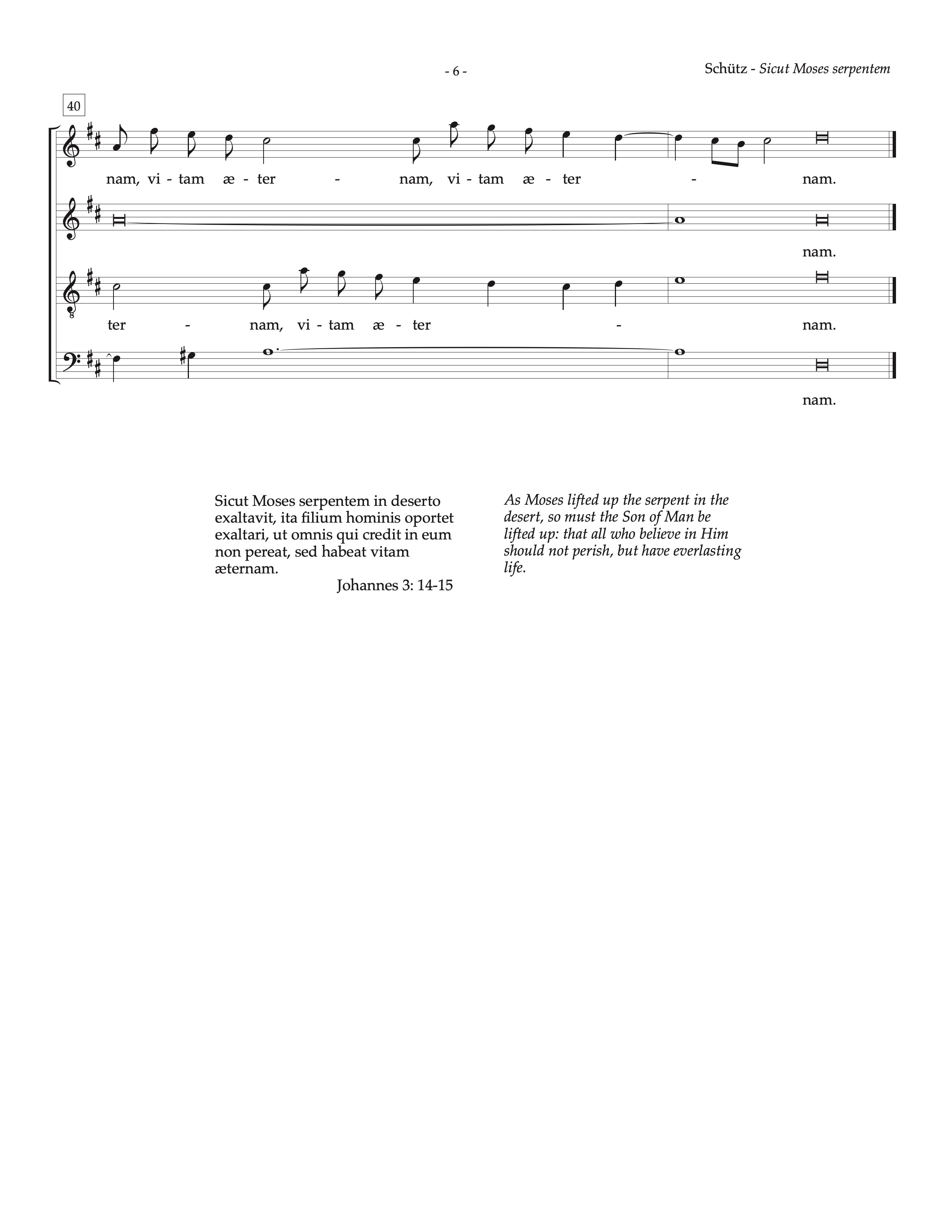

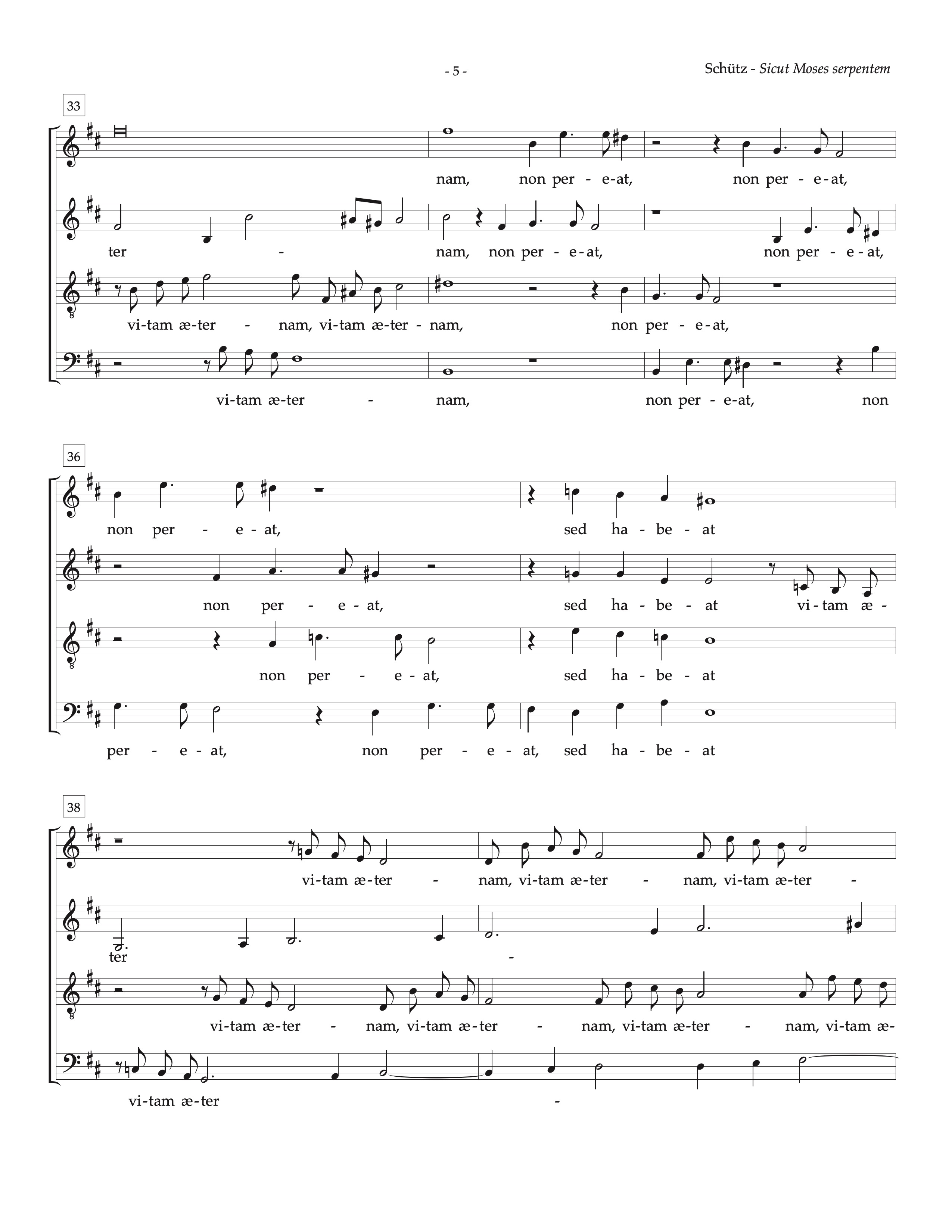

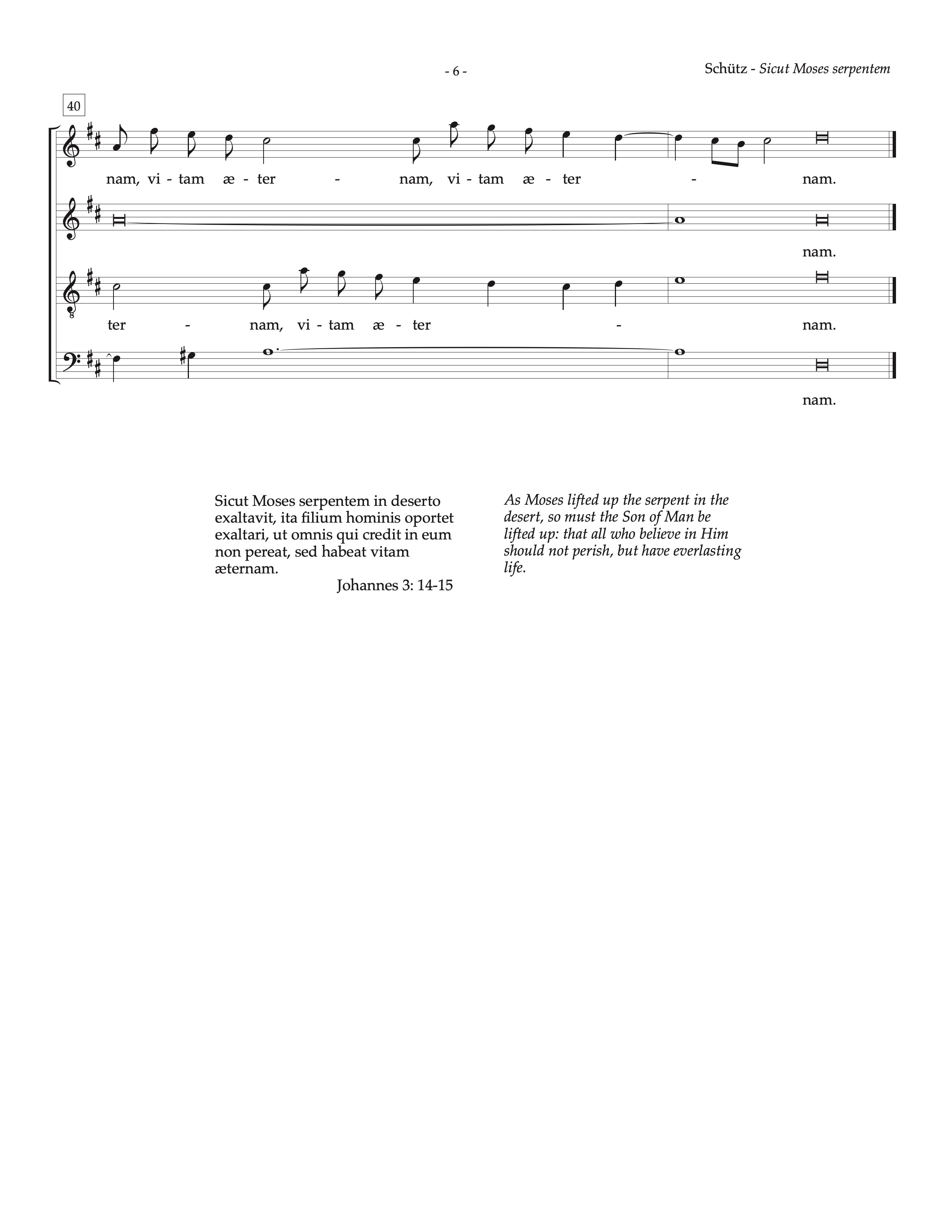

All come together for the words “ut omnis qui credit in eum” (“that all who believe in Him”) to represent the unified idea of “all.” Then comes an interesting series of rapid off-the-beat stresses on the word “non” in the phrase “non pereat” (“shall not perish”). The motet ends with a rising series of motifs on the climactic words “sed habeat vitam aeternam” (“but have everlasting life”), notable both for the extended nature of the series (“everlasting”) and for the ascent up the scale to represent the arrival in heaven.

End of Lesson 10. Click here to continue to Lesson 11, for April 29. Click here to return to the Lesson List.

|

|