LEARNING MORE ABOUT THE MUSIC WE SING

|

Lesson 7, for April 13

In our canceled concert for April 3, Byrd’s O salutaris hostia was to be followed by three short sacred works in English by Henry Purcell (1659-1695), who lived approximately a hundred years after Byrd. During Byrd’s lifetime the English Church had gone through turbulent times, changing to Anglican toward the end of Henry VIII’s life (starting officially in 1534 upon Henry’s break with Rome in order to have his marriage to Catherine of Aragon annulled), becoming more radically Anglican under Henry’s young son Edward VI (reigned, starting in 1547, from age 9 to 15), changing violently back to Catholic under Mary Tudor (reigned 1553-1558), and changing back again to Anglican under Mary’s half-sister Elizabeth (reigned 1558-1603).

Thomas Cranmer was the Archbishop of Canterbury who authorized Henry to break with Rome, and once Edward came to the throne in 1547 Cranmer effectively ruled the country, certainly the Church. Three years before Henry’s death Cranmer had written a letter to the king in which he laid out in just a few words his vision for the appropriate type of music to be sung in the Anglican Church: it “would not be full of notes, but, as near as may be, for every syllable a note; so that it may be sung distinctly and devoutly.” In other words, it would not be like Byrd’s O salutaris hostia, but much simpler, one note per syllable. Once fully in control during Edward’ reign, Cranmer made sure composers of sacred music for the Anglican Church followed his prescriptions. Byrd’s teacher and colleague Thomas Tallis showed that even under Cranmer’s severe restrictions wonderful music could be composed, and Purcell, a hundred years later, continued in that tradition. You will see that the three short pieces by Purcell for our April 3 concert are all basically one note per syllable.

However, musical style had not stood still for the hundred years separating Tallis and Byrd from Purcell. The biggest change was in composers’s ability to make music more expressive, more directly reflective of the meaning of the words being sung. The practice of having the words determine the shape and sense of the words is known as musical “rhetoric,” sometimes called word-painting. Words illustrated this way in music are also sometimes called madrigalisms.

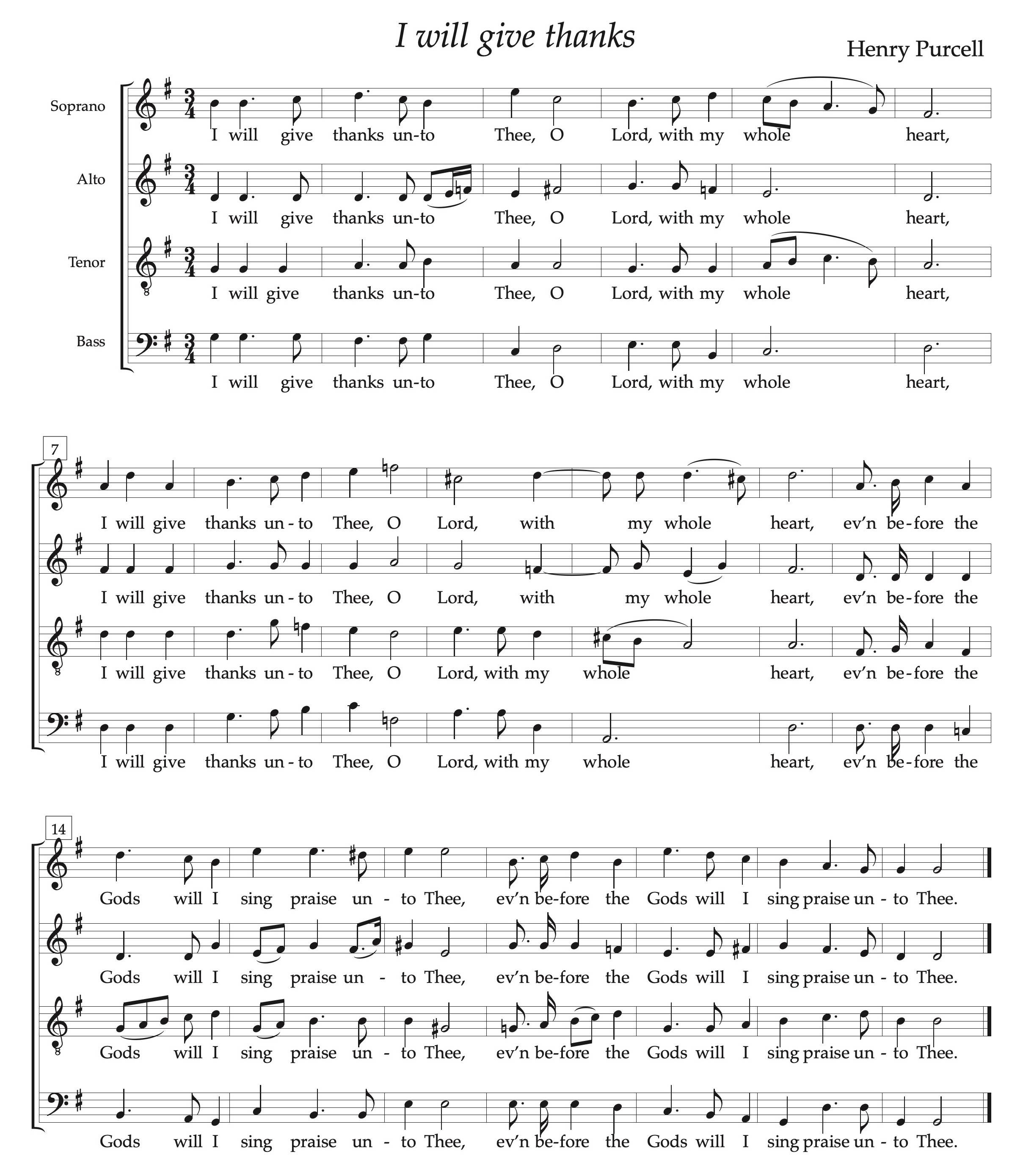

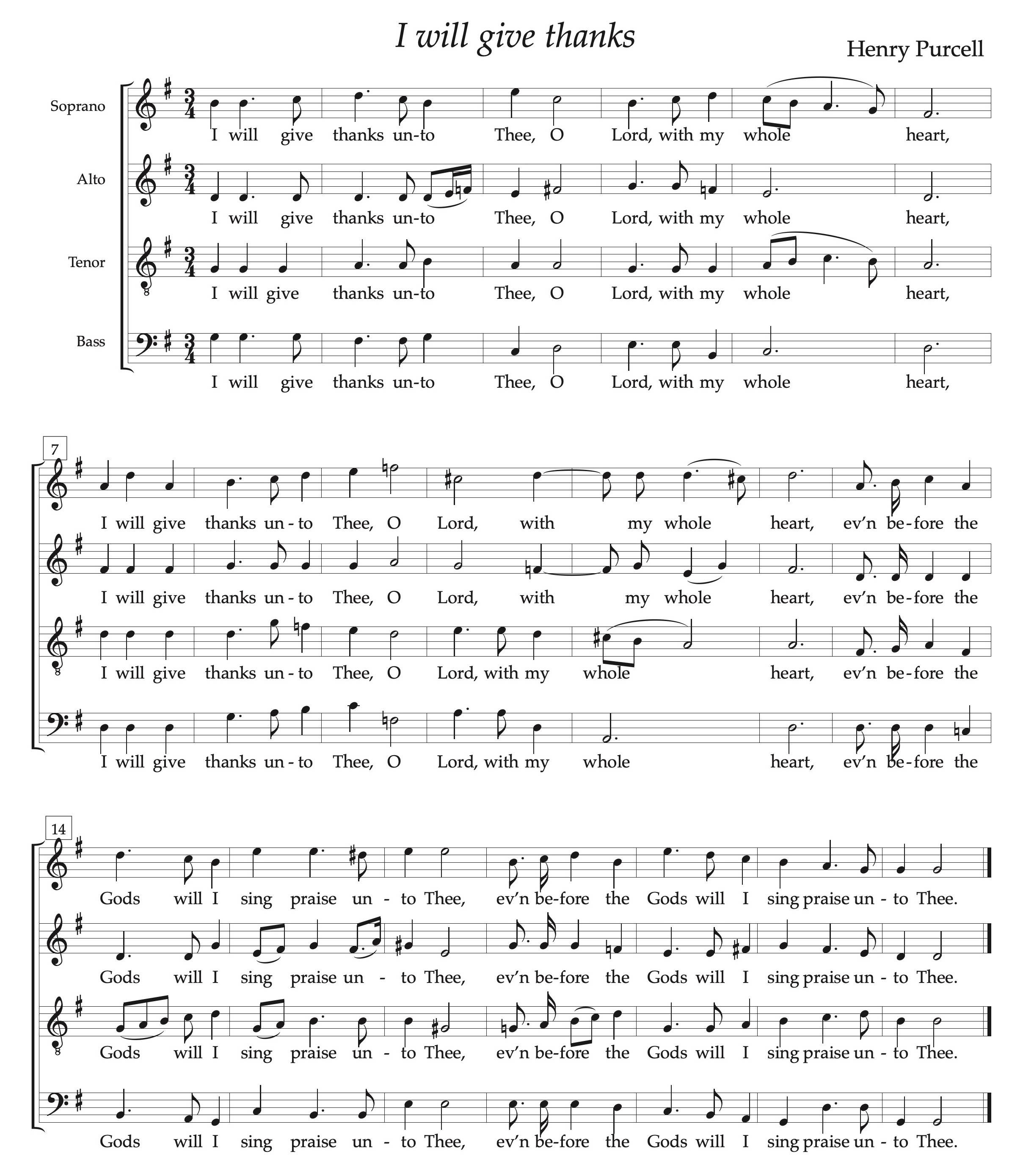

Looking first at the opening of Purcell’s I will give thanks, we see that the rhythm of the music exactly captures the rhythm of the spoken words, with the words “thanks” and “whole heart” being emphasized. At mm. 9-10, to the words “O Lord,” Purcell uses both rhythm and surprise harmony to create the effect of the poet crying out to God, then once again using an elaborate musical texture to capture the meaning of the word “whole.” Both times the words “sing praise” occur, Purcell puts the emphasis on “praise” by a longer note, but a note that occurs on beat two of the measure, thereby avoiding a simplistic sing-song effect.

End of Lesson 7. Click here to continue to Lesson 8, for April 15. Click here to return to the Lesson List.

|

|