CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VII. Jacques Maritain Center :

St. Thomas Aquinas / by Placid Conway, OP

Jacques Maritain Center :

St. Thomas Aquinas / by Placid Conway, OPPART III: EVENING.

HIS WRITINGS: SECOND PERIOD.

WHILE the Angelic Doctor was reading his Office for Corpus Christi before Urban IV, the Pontiff's eyes were suffused with tears: never was guerdon better earned, so, retiring into his oratory, after a little while he came forth bearing the large silver dove containing the sacred species, and gave it as a memento. Then he charged St. Thomas to write a luminous commentary on the Four Gospels, compiled exclusively from the writings of the Fathers. Under the title of "Catena Aurea," or "Golden Chain," he composed the fullest commentary ever drawn from Patristic sources, culled impartially from Eastern and Western Fathers, and for the most part written from memory. St. Matthew's Gospel, finished in 2264, was dedicated to the Pope, who died soon after; the other three Gospels followed, but St. John's was dedicated to his fellow religious, Cardinal d'Annibaldi. Directly Pope Clement IV assumed the tiara in February, 2265, he summoned Thomas to Rome. If love of truth made our saint always. to seek the quiet of retirement, the call of obedience found him ready for further work. He now put forth another argumentative treatise, begun long before in Paris, in which Arabian pantheism yielded before the power of the syllogism; its title is: "On the Unity of the Intellect, against the Averroists". Averroes, the cultured Arabian physician, while outwardly professing to be a Christian, was an atheist at heart. Christianity he called an impossible religion, Judaism one for children, Mohammedanism one fit for hogs. The basis of his errors was this, that all men have but the one intellect, and consequently but one soul: consequently, there is no personal morality. "Peter is saved: I am one intellect and soul with Peter; so I shall be saved." Presumably the deduction from unity of intellect with Judas was forgotten. From the appearance of St. Thomas's work, the philosophy of Averroes was consigned to the antiquities of the buried past.

Meanwhile the Father-General, Blessed John de Vercelli, and his brethren, were conscious of the loss to the Order in being so long deprived of the holy doctor's services: so now, by agreement with Pope Clement, he returned to the cloister-school of Santa Sabina on the Aventine. The General Chapter held at Montpellier in 2265 assigned him to Rome, to resume teaching. "We assign Friar Thomas of Aquino to Rome, for the remission of his sins, there to take over the direction of studies. Should any students be found wanting in application, we empower him to send them back to their own convents." He now drew up the scheme of his most memorable work, the triumph of his life, the great "Summa Theologica," which he was not destined to complete even after nine years of labour. The very daring of the scheme, comprising the whole range of dogmatic and moral theology, fills the world with astonishment, while its intricacy of argument can be likened only to some gorgeous tapestry woven by the genius of thought. Let us hear his introductory prologue.

"Since the teacher of Catholic truth ought to instruct not merely the advanced, but it falls to him likewise to teach beginners, according to the saying of the Apostle in 1 Corinthians III. 1 : 'As unto little ones in Christ, I gave you milk to drink, and not meat'; the purpose of our intent in this work is to treat of the matters of the Christian religion in such a way as to adapt them to the instruction of beginners.

"Now we have observed that novices in such learning are very much hindered by the writings of some individuals; partly from the multiplying of useless questions, articles, and arguments; partly again because the themes to be learnt are not dealt with in their proper order, but just as the explanation of text-books called for, or as occasion for discussion arose; and, finally, in part because the constant repetition of the same matter begot weariness and confusion in the minds of the listeners.

"Endeavouring then to avoid these and similar drawbacks, and confiding in the Divine assistance, we shall endeavour to traverse briefly and clearly all the matters of sacred doctrine, according as the matter in hand shall permit,"

Drawing exhaustively upon theological founts, he brings in Philosophy simply as a handmaid, to confirm from Reason the teachings of Revelation. This Sum of Theology is the most perfect body of truth, the fullest exposition of theological lore ever given to the Church. When one calls to mind the frequent interruptions from daily lectures, frequent preaching and journeys afoot, the marvel is that it ever neared completion. The First Part treats of God and Creation. In rigid sequel the treatises deal with God's Existence, Unity, Attributes, and Trinity. Creation comprises God's creative action, the Hexameron or work of the six days, the Angels, and lastly Man. All this is set forth in 119 Questions, or divisions, subdivided into 584 articles, making one great folio. The Second Part is subdivided into two divisions known as the First of the Second and Second of the Second, yielding two more folios. The former deals with the End of man, which is the Vision of God; with Morality, Passions, Sin, Theological and Moral Virtues, Gifts of the Spirit, Law, and Grace. In comprises 114 Questions, containing 619 articles. Whereas this Part deals with the subject matter under common consideration, the Second of the Second goes over the same ground in detail, under particular consideration, ending with the states of bishops and religious. This occupies 289 Questions, with 916 articles. The Third Part treats of Redemption through Christ: the chief treatises are the Incarnation, the Life of Christ, thus forming a perfect Christology; the Sacraments as sources of grace applying the fruits of Redemption, then in detail -- Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, and Penance. When mid-way through the treatise on Penance, the pen was laid down to be resumed no more. With his own hand he wrote ninety Questions, containing 539 articles. The rest of the Part is all his, but compiled by another hand: it is drawn from his Commentary on the Fourth Book of the Sentences: this supplement contains ninety-nine more Questions distributed into 442 articles; making the Third Part complete under 289 Questions, with 981 articles. This vast arsenal of Catholic Doctrine has altogether 497 Questions, subdivided into 2481 articles. The First Part, written in Rome, occupied him during two years; the Second Part was written in Bologna and Paris, the fruit of five years' toil; the Third Part was compiled in Naples. Small wonder then that the words of a Pope are inserted as an antiphon in his festival office: --

As a river of limpid knowledge

He irrigates the entire Holy Church.

Ten years had elapsed since the attack was made on the Mendicant Orders by William de Saint Amour, who was forced to retire apparently a broken man. Once more he returned to the fray with a more plausible work, which the Pope handed over to the Master General for St. Thomas to confute. In 1268 appeared the Apology for the Religious Orders, entitled "Against those who would withdraw others from entering the Religious State". He wrote this Apology for a purpose, and he attained it: the purpose was to combat prejudice against youth seeking the state of perfection. Presently he added another treatise, "On the perfection of the Spiritual Life," to show wherein Christian perfection lies essentially, and by what means it may be attained.

All perfection consists essentially in Divine Love. "God is Charity," hence, since human perfection comes of progressive likeness to God, it follows that it comes of the infusion and exercise of Charity. It is the one abiding gift which never falls away. The Moral Virtues give fitness for the life of blessedness in heaven: Faith and Hope pass into Vision and Embrace, but Charity alone endures. The charity of creatures comprises four degrees, as the ascending scale to the Holiest Himself. There is the love of the Angels, whose choirs attain their zenith in the blessed Seraphim. The sons of light are the sons of fire. "Thou makest thine Angels spirits, and thy ministers a flame of fire" (Psalm cxxi. 4). Next in order comes the love of the Blessed, ever actually engrossed in the thought of God, who can never turn their faces away: with them their love is their life, and the outcome of their degree of charity when on earth. But, as St. Thomas teaches, love such as this is beyond man's earthly powers. "It is not given to man upon earth to think actually of God at all times, ever actually to love Him." The remaining degrees concern us men in our state of pilgrimage below. The charity of earth is twofold: the higher is that of such as embrace and keep the Gospel counsels of perfection, by professing voluntary Poverty, perpetual Chastity, entire Obedience. All are in the state of perfection who thus follow the Master out of love. The lowest rank is of such as are only called to, and are content with, what is of precept, the simple keeping of the Commandments. Thus the Religious State is one of perfection, but actual perfection is the heroism of fulfilment, the bloodless martyrdom of charity.

In Rome during the whole Lent of 1267 our Saint preached in the Old Saint Peter's Basilica: taking Christ's Passion for his theme, he spoke so strongly against public vices that a change of morals was observable on all sides. During the Good Friday sermon he wept aloud, so as to move the whole audience to tears: on the Easter Day and during the Octave he made them all to thrill with joy and hope. As he was passing out through the porch, a woman long afflicted with a flow of blood came behind him, kissed his cloak, and was instantly cured. A remarkable Jewish conversion made in the previous winter stirred the hearts of the Romans. Cardinal d'Annibaldi having secured Thomas for a few days' visit to his country residence at Molara, invited two Rabbis to meet him, to enjoy his rare gift of conversation. Polite speech soon grew to argument between the well-measured opponents, regarding the Messiah, for it was Christmas Eve. The Rabbis pleaded their cause with learning and earnestness, but all that they could advance was met by clear proofs to the contrary, put before them with all meekness and sincerity. They were so tenacious of their convictions, however, that all he said produced no immediate results: yet at the same time they were so captivated by his manner, that they promised to repeat the visit on the morrow. That night of the Christmas mystery Thomas spent before the new and abiding Bethlehem, "the home of bread," on the altar: where argument failed, prayer prevailed, and on Christmas Day he received them into the Christian fold.

The holy Doctor acknowledged to friends, that, on every Christmas night, he obtained some special favour from God, some vision, or deeper insight into the glories of Christ. His exquisitely tender devotion towards our Lord stands revealed in this prayer

"Most tender Jesus, may Thy most sacred Body and Blood be my soul's sweetness and delight, health and holiness in every temptation, joy and peace in every sorrow, light and strength in every word and work, and my last safeguard in death."

St. Thomas was now held in universal esteem as an oracle sent of God: halls and churches were taxed to their utmost capacity to contain his eager auditory, and those listeners were no mere youths, but Doctors of the schools, Bishops and even Cardinals. He had such mastery over mind and senses that he dictated to four secretaries at the one time on widely different subjects, and was known to dictate still while fast asleep. Such is the testimony of two such secretaries, Reginald of Piperno and Hervey Brito. So capacious was his memory, that he never forgot what he had once read. One evening while dictating the treatise on the Holy Trinity, he held the candle so as to assist the scribe: soon he became so lost in sublime thought that he let the candle burn out in his fingers, without being conscious of the pain.

At Pentecost of the year 1267 he took part in the General Chapter of Bologna, and witnessed the solemn translation of St. Dominic's relics: it was on this occasion that the Pope sent him a Brief requiring him to choose and send two friars to assist the Bishop of Narenta in Dalmatia. The University prayed the Chapter to leave him in Bologna, so he accepted a chair in the public schools. It was a joy for him to live in the home wherein St. Dominic died: many were the nights he spent in prayer before the Holy Father's tomb. It is an interesting fact that he composed the questions on Beatitude and the Beatific Vision in this hallowed spot. Out of consideration for his merits, two new foundations were bestowed upon the order. Archbishop Patricio Matteo gave St. Paul's church in Salerno, with its houses and gardens, "to his friend and former master, Thomas of Aquino". Abbot Bernard of Monte Cassino, in a Synod of the clergy within his jurisdiction, made over a similar establishment in the town of San Germano.

In 1268 the house of Aquino was restored in its honours and estates, whereat the man of God adored heaven's judgments and designs, even while he poured out thanks. At the request of the Master General he composed a short work on "The Form of Absolution": for the King of Sicily he wrote the first two books of the treatise "On the Government of Princes," but the third and fourth are by some other pen.

Summoned to attend the General Chapter in Paris in the year 1269, at the voice of authority he remained there as Regent of Studies. The world of letters might come to him, if it so listed, but he would not go out to it, being pre-occupied with the moral section of his "Summa". He continued on terms of holy intimacy with St. Louis IX, until that Preux Chevalier sailed for the Holy Land in 1270. During his two years' residence in Paris he published these works: "On the Soul"; on "Potentia"; "On the Union of the Word"; "On Spiritual Creatures"; "On the Virtues"; "On Evil".

One day he accompanied the novices to the abbey church of St. Denys, which was the burial place of the Kings of France; there they sat a while to rest upon a hillock, and surveyed the city stretched before them. Hoping to hear some words of wisdom, one of the party observed: "Master, see what a splendid city Paris is; would you not care to be its lord?" Thomas gazed for a moment, then replied: "I would rather have St. Chrysostom's Homilies on Matthew's Gospel. What could I possibly do with such a city?" "Well Father," rejoined the novice, "you might sell it to the King of France, and build convents for the Friars Preachers in many a place." "In good sooth," said the saint, "I should prefer the Homilies. If I had the government of this city, it would bring me many cares: I could no longer give myself to Divine contemplation, besides depriving myself of spiritual consolations. Experience truly shows this, that the more a man abandons himself to the care and love of temporal things, the more he exposes himself to lose heavenly blessings." "O happy Doctor," exclaims Tocco, "despiser of the world! O lover of heaven! who carried out in conduct what he taught in words, who thus despised earthly things, as if he had already caught a glimpse of the heaven he was looking forward to possess."

A man's character can be accurately measured by his friendships. While bearing himself affably towards all, the Angelic Doctor had but few intimacies, and these were with persons of singular holiness. Now since friendship is based on resemblance, and results in equality and expansiveness, one is not surprised to find that his great heart opened to the learned, many of whom are enrolled with him in the catalogue of the Blessed.

He kept perfect control over his emotional and sensitive faculties. When the rude surgery of the time required that he should be bled, and once when it was deemed necessary to cauterize his knee with a hot iron, he put himself into a state of contemplation, and felt nothing whatever of the operation. When preaching, he stood firm and erect, the clasped hands resting on the pulpit, the eyes closed, the head upturned and thrown somewhat backwards. At table he often sat lost in thought, with open eyes gazing upwards; it was the same in the garden, the cloister, the cell. He frequently gave this injunction to Reginald, his chief secretary: "Whatever you see happen in me, do not interrupt me". It was in 1270 he completed his Commentary on St. Paul's Epistles, during the composition of which he was favoured with the visible appearance of the Apostle, who came to his assistance in expounding the more abstruse passages.

Recalled to Rome in 1271, he finished the second section of the Second Part of his "Summa" in the peaceful priory on the Aventine hill, and began the Third Part. His time was now devoted to this work, to daily lectures, and to writing a Commentary on Boetius.

St. Thomas possessed a master mind ranging over the whole domain of Philosophy: after seven centuries he is abreast of our times in science, while not a few of our latter-day "discoveries" may be read in his pages. The twentieth century has gone back to him for its epistemology, or science of doctrine, to his canon of "Nihil in intellectu quin priusfuerit in sensu". With him, ethics is no dry digest of "agibilia," it is the most practical of the sciences, for it is the shaping of human conduct. The political and social economist must consult him for sound economics, as Pope Leo XIII did in his Encyclical "Rerum Novarum"; there in many an eloquent passage he will find as the basis of social economy man's fundamental right of ownership, while the determination falls to the State. In Psychology this sage holds firm for the real distinction between soul and faculties, and between the faculties themselves; feeling is largely identified with will, but he is no patron of Rosminian consciousness as being the soul's nature. It is to St. Thomas we go for the sound philosophical principles of rational physics. His exposition of cosmology, given in the treatise on Creation, which is contained in the First Part of the "Summa Theologica," is out and out more scientific than all theories of atomism, chemical forces of dynamism, or pretended affinities of later days. He is a creationist, and holds to matter and form as the substantialities of things. Primary matter is the subject of all the substantial transformations of the corporeal universe. Substantial form is the likeness of a Divine idea, which, being expressed in matter, constitutes it in a determined substance: as a consequence, the degrees of beings depend on the perfection of forms.

Nature is the first principle of motion and of rest. All primitive substantial forms as well as primary matter must come of creation: his teaching shows the impossibility of our modern biogenesis. The variation of gravity he explains not by addition or subtraction of extraneous particles, but by matter itself becoming rare or dense; hence heaviness is a result of density. He was well acquainted with ether, admitting as he does of an ethereal and most subtle bodily substance everywhere diffused in the interplanetary spaces, as the vehicle and subject of the reciprocal operations of the stars and planets. Such is the explanation of the diffusion of light and heat, in agreement with experience. Ages before Melloni he said: "All light is productive of heat, even the light of the Moon". Those who talk of sex in plants as a modern discovery had better read his "Commentary on the Third Book of 'Sentences'". "In the same plant there is the twofold virtue, active and passive, though sometimes the active is found in one, and the passive in another, so that the one plant is said to be masculine, and the other feminine." [III," Sent.," Dist. III, Quest. II, art. 1.] He was well acquainted with seminal causes, the laws of qualities, attraction, mechanical activity, and inertia of bodies: in the matter of chemistry there is no substantial discrepancy between his teaching and the true principles of modern science as to substantial transformation.

HIS HEROIC SANCTITY.

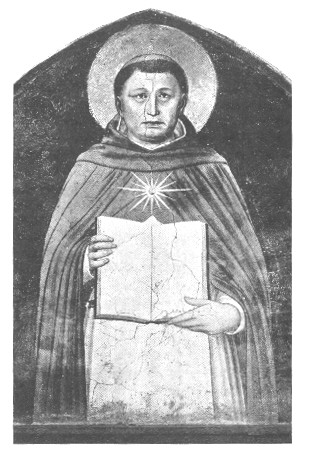

OUR saint presented a very noble and striking figure. He was of lofty stature, of heavy build but well proportioned, while his countenance was of our northern complexion, "like the colour of new wheat," as we read in the deposition for his canonization. The features were comely, the head massive and well shaped, the forehead lofty, and he was slightly bald. Judging from his portrait, the general aspect was calm, sweet, majestic; the deep meditative eyes speak of gentleness, the nose is long and straight, the mouth very firm. Taken altogether, the features reveal the inner charm of his soul.

The earliest known portrait is a superb painting on a panel by an unknown artist of the fifteenth century, now preserved in the Louvre at Paris. A replica of inferior quality is to be seen in the suppressed Carmelite convent at Viterbo. An inscription beneath reads thus: "The true portrait of the Angelic Doctor Saint Thomas Aquinas, as described by a disciple ".

He was the saint of sublimest thought, which he nourished with' spiritual reading. "In such reading I try to collect devout thoughts, which will lead me easily to contemplation."

The basis of his character and conduct was holy humility. The advice he tendered to others, he took to heart himself. "Love of God leads to self-contempt, whereas self-love leads to the contempt of God. If you would raise on high the edifice of holiness, take humility for your foundation." In a moment of confidence he made this candid avowal to Fr. Reginald of Piperno. "Thanks be to God, my knowledge, my title of Doctor, my scholastic work, have never occasioned a single movement of vain glory, to dethrone the virtue of humility in my heart." Dignities he would never accept: he held no office in his Order. He declined the lordly abbacy of Monte Cassino, even though the Pope offered to let him keep his habit of a Friar Preacher. Clement IV tried to secure his acceptance of a Cardinal's hat, and expedited the Brief creating him Archbishop of Naples, but all to no purpose; when death was in view, he uttered this exclamation: "Thanks be to God, I die as a simple religious".

He was very tenacious of poverty; all his journeys were made on foot, his habit was of the poorest, he kept rigidly to the common life. Fr. Nicholas de Marsiliaco has furnished us with this testimony: "I was in Paris with Fr. Thomas, and I declare before God that never have I seen in any man such degree of innocence, such love of poverty. In writing his 'Sum against the Gentiles' he had not sufficient copy-books, so he wrote it on scraps of paper, although he might have had books in abundance, had he been so minded, but he had no concern for temporal affairs." If mitre and scarlet had no attractions, still less had the rich revenues of an abbey, St. Peter ad Aram, in Rome, when offered by Pope Clement. He would keep nothing for his personal use, no chalice, no manuscript, while he held dainties in abhorrence, and practised austerities.

As to obedience, it was one of his sayings that an obedient man is the same as a saint. He was just as prompt and hearty in obeying his Prior as in obeying the Father-General, or our Lord the Pope. A lay-brother in Bologna, having occasion to go out of the convent to make some necessary purchases for the table, had leave to summon the first friar he met to bear him company, as the rule required. St. Thomas was pacing the cloister at the moment, to whom the brother spoke thus: "Good father, the Prior wants you to follow me through the town". Thomas complied, but as they strode through streets and market he was unable to maintain the pace, being slightly lame, for which he was soundly rated more than once. The amazed townsfolk interposed with heated speech, reminding the testy one of his companion's dignity, to say nothing of his infirmity. The simple brother fell at once to his knees to implore forgiveness, for he had no idea of the strange father's name or rank: St. Thomas, however, reassured him by saying that each was simply carrying out an obedience. It was then he uttered the oft-quoted maxim: "Obedience is the perfection of religious life: thereby a man submits himself to his fellow-man for the love of God, just as God became obedient to men for their salvation".

With regard to the holy chastity, the Angelic Doctor is both patron and pattern of the angelic virtue: youth and maiden, priest and cloistered soul, acclaim him alike as their model and protector. "Incorruption bringeth nearer to God" (Wisdom, vi. 20). In his "Commentary on St. Paul's Corinthians, "Chapter VII, lesson 6, he rehearses eight blessings of Virginity.

1. It preserves cleanness of the flesh. 2. It beautifies and adorns the soul. 3. It makes like unto the Angels of heaven. 4. It espouses to the Christ. 5. It gives union with and closeness to God. 6. It surpasses other states. 7. It breathes forth the odour of good repute. 8. It invites to the eternal nuptials. Of these the most valuable are the fourth, fifth, and last. It espouses unto the Christ by giving fitness for union with Christ's Body in Holy Communion, and to the priest for making, handling, and dispensing the same. Hence the Poet Virgil places the life-long chaste priest in the Elysian fields.

Quique sacerdotes casti, dum vita manebat.

-- AEneid, vi. 66i.

It gives union with God, and closeness, by bestowing fitness for contemplation. "Where there is cleanness there is understanding;" "What removes a hindrance is an indirect mover," as St. Thomas constantly urges. Chastity lends fitness for contemplation by removing carnal desires, which so affect the mind's eye that even the truest see sin through a distorted lens. Lastly, it invites to the eternal nuptials. The closer anything approaches to its principle, the more perfect it becomes: but God, Who is our Principle, is a most Pure Spirit: therefore, Chastity leads up to perfection. But our last end is to be one of inseparable union with the all-clean God, as guests at the nuptials of the Lamb; therefore Chastity disposes for such union. The saint lived and died a perfect virgin in mind and body: his heroism in youth drew Angels down from heaven. "He who loves cleanness of heart, for the grace of his lips, shall have the King for a friend" (Proverbs xxii. 11)

The depth of his Divine love, God alone can sound: it was revealed in a measure by his life, but he never spoke of it. "It is a good thing to conceal the King's secret" (Tobias XII. 7). All the world read his heart, his human kindness, his deep friendships. No hard saying ever crossed his lips: he could slay an argument, yet spare a foe. Without guile in his own soul, he could with difficulty be brought to believe in the guilt of others. When he sat in the tribunal of penance, in God's Mercy-seat, it was with a melting heart of pity. Two things he loved especially: these were the Order of Preachers, and God's poor. From love of the brethren he blessed the church bell at Salerno, foretelling that it would toll of itself to give warning of an approaching death. It kept its miraculous power until it fell and was broken in the seventeenth century. [1 Its power was still attested in 1678.] Like St. Dominic he was "ever joyous in the sight of men," uniting the grace of noble manners to the reserve of the religious. He inculcated and observed the remembrance of God's presence. "Be assured," he would say, "that he who walks faithfully in God's presence, and who is ready to give Him an account of his actions, will never be parted from Him by yielding to sin.

Prayer was for him the very breath of his life. Frequently he urged St. Augustine's maxim: "He knows how to live rightly, who has learnt how to pray properly". In the funeral discourse at his obsequies, Fr. Reginald bore this testimony: "During life my Master always prevented me from revealing the wonders which I witnessed. Of this number was his marvellous learning which uplifted him beyond all other men, which he owed less to power of genius than to the efficacy of his prayer. Truly, before studying, or lecturing, reading, writing, or dictating, he began by shutting himself up in secret prayer: he prayed with tears, so as to obtain from God the understanding of His mysteries, and then lights came in abundance to illumine his mind. When he encountered a difficulty, he had recourse to prayer, and all his doubts vanished."

The Angelic teacher was likewise an Angelic singer: nothing but inability from sickness ever kept him from Choir duty. In the opening of his treatise, "On the Separated Substances," that is, the Angels, he acknowledges his absence for a time from Divine praise in the Choir, due to frequent attacks of sickness. "Being deprived of assisting at the solemnities of the Angels, we must not allow a time consecrated to devotion to be unoccupied, but rather compensate by study for the loss of assisting at the Divine Office."

His devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary was tender and deep, as evinced by his writings, and by this prayer: --

"Dearest and most blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of God, overflowing with affection, Daughter of the Sovereign King, and Queen of the Angels: Mother of Him Who created all things, this day and all the days of my life I commend to the bosom of thy regard my soul and my body, all my actions, thoughts, wishes, desires, words, and deeds, my whole life, and my end: so that through thy prayers they may all be ordered according to the will of thy beloved Son, our Lord Jesus Christ. Lady most holy, be my helper and my comforter against the attacks and snares of the ancient foe, and of all my enemies."

A few days before his death he told Fr. Reginald that Christ's dear Mother had appeared to him on several occasions, assuring him that his life and writings were pleasing to God, and that he would persevere in his state. St. Vincent Ferrer and St. Antoninus of Florence affirm that in his difficulties he used to turn to her as a child to a mother. Then she would stand visibly before him, and, turning with a smile to the Divine Babe in her arms, ask Him to bestow the enlightenment he sought.

A complete Mariology has been compiled from his works, drawing out Mary's singular graces. [The work of Rev. Dr. Morgott, Ratisbon.] He upheld the privilege of her exemption from original sin. It is an old-established saying, that, "with St. Thomas a man can never be wrong, nor can he be right without him". That he upheld Mary's sinless conception can be established from extrinsic and intrinsic evidences. It is the verdict of his weightiest exponents, such as Capponi de Porrecta, Joannes a Sancto Thoma, Natalis Alexander, John Bromeyard of Oxford, and many more. At the Council of Basle, John of Segobia upheld the Immaculate Conception from St. Thomas's writings. Theologians of first rank have held the same view, such as Vega, Eichof, Nieremberg, Sylveira, Thyrsus Gonzalez, Stefano Chiesa, Plazza, Spada, Cornoldi, Cardinal Sfondrato, Cardinal Lambruschini, etc.

If we open his writings we have the intrinsic evidences of various passages. In his "Opusculum," LXI, de Dilectione Dei, et Proximi, we meet this passage: "For the more complete manifestation of His power, the Creator made a mirror which is brightest of the most bright, more polished and more pure than the Seraphim, and of such great purity that there can not be imagined one more pure, except it were God: and this mirror is the person of the most glorious Virgin".

In his "Commentary on the First Book of the "Sentences,'" he twice makes use of this sentence: "The Blessed Virgin Mary shone with a purity greater than which under God cannot be comprehended." (Dist. XVII, Quest. II, art. 4, 3m). Here is his proof: "Increase of purity is to be measured according to withdrawal from its opposite, and since in the Blessed Virgin there was 'depuratia' from all sin, she consequently attained the summit of purity; but yet under God, in Whom there is no capability of defect as is in every creature of itself". And again he writes in Dist. XLIV, Quest. I, art 3 "Purity is increased by withdrawal from its opposite, and consequently some created being can be found purer than which nothing can be found in creatures, if never sullied by defilement of sin, and such was the purity of the Blessed Virgin, who was exempt from original and actual sin". Some think that the expression "depuratio" argues cleansing from stain; but such was not the meaning which St. Thomas attached to the word. The Holy Fathers frequently use this word with regard to God Himself. St. Augustine, Peter Lombard, Fulgentius, Ferrandus, Hugh of St. Victor, also use it of God, while a whole host of writers employ it when speaking of Christ: St. Thomas uses it twice in his treatise on the Incarnation, and Dionysius makes use of it with regard to the heavenly Hierarchies. So then, "depuratio ab omni peccato" does not mean "cleansing from all sin," but "exemption from all sin". The Angelic Doctor knew the scientific value of the term used, and his critics do not. The expression used above "immunis a peccato" is the one employed by Pope Pius IX in proclaiming the dogma.

There is no need to expatiate on the fact that St. Thomas was a consummate logician, and consequently not likely to teach in one part of his writings the contrary to what he lays down in another. In the First Part of the "Summa Theologica," Question XXV, art. 6, ad. 4, he writes: "The Blessed Virgin, in that she is the Mother of God, has a kind of infinite dignity from the Infinite Good, which is God, and on this account nothing better than her can be made, just as there ~is nothing better than God ". Again in the Third Part, Question XXVII, art. 3, he says: "The closer a thing approaches to its principle in any order, the more it partakes of the effect of such principle. Hence Dionysius states in the fourth chapter of the 'Heavenly Hierarchies,' that 'the angels being nearer to God, share more fully of the Divine perfections than men do'. But Christ is the principle of grace authoritatively according to His Divinity and instrumentally in His humanity, as St. John declares in the first chapter (of the Gospel). 'Grace and truth are made through our Lord Jesus Christ.' But the Blessed Virgin was closest to Christ in His humanity, since He drew His human nature from her, and therefore she ought beyond all others to receive the fullness of grace from Christ."

From these two passages we gather St. Thomas's teaching as to Mary's prerogatives. 1. She possessed an almost infinite dignity from her closeness to God, in this surpassing the angels. 2. She ought, that is, she had the right, to receive the fullness of Divine grace beyond all other creatures. Since then it is the work of grace to purify the soul by imparting to it the Divine beauty, it follows necessarily that grace wrought absolute sinlessness in her soul, and created boundless holiness. In this dual capacity of closest union with God, and being the appointed instrument of Christ's humanity, she surpassed the angels, who never knew sin: she had a kind of infinitude in merit which none of them ever could have. How then can such teaching of St. Thomas be reconciled with the idea that Mary had ever been sullied for an instant with original sin? Let the theory be once admitted that Mary had been so defiled, then his two principles given above fall to the ground; admit his principles, and the Immaculate Conception is the logical result. The holy Doctor was well aware of the grace bestowed on those pre-eminent saints, Jeremiah and John the Baptist, yet he does not hesitate to place Mary incomparably beyond them, and attributes their sanctification to her as well as to her son. She must then, logically speaking, have received a greater grace than cleansing after conception.

In his exposition of the "Hail Mary" he distinctly declares the doctrine. "Thirdly, she exceeds even the angels in purity: because the Blessed Virgin was not only pure in herself, but even procured purity for others. She was most clean from fault, because she incurred neither original, nor mortal, nor venial sin."

In his "Commentary on the Epistle to Galatians," III, lect. VI, the original text runs thus: "Of all women I have found none who was altogether exempt from sin, at least from original sin, or venial, except the most pure, and most worthy of all praise, the Virgin Mary".

Again in his "Commentary on the Epistle to Romans": "All men have sinned in Adam, excepting only the most Blessed Virgin, who contracted no stain of Original Sin".

Such are the readings of the first MS. Codices and early printed versions. In a marginal note written by St. Vincent Ferrer in his copy of the "Summa," Part III, Question XXVII, art. 2, ad. 2m, are these words: "The Blessed Virgin was exempt from original and actual sin". It was these original texts of early manuscript Codices which early defenders of the Immaculate Conception quoted for their opinion, such as St. Leonard of Port Maurice, Bernardine de Bustis, B. Peter Canisius, Cardinal Sfondrato, Salmeron, and many more. Weighty theologians such as Velasquez, Peter of Alva, Eusebius Nieremberg, Frassen, Lambruschini, Gual, and Palmieri, following the critical method of Hermeneutics, have held and shown that many passages of St. Thomas have been changed or interpolated. Let it suffice to adduce three apologetic writers who denounce such practices, and vindicate the purity of his text. Bishop Vialmo, a Friar Preacher: "Pro defensione Sancti Thomae"; Egidius Romanus, a disciple of St. Thomas "Castigatorium: in corruptorem librorum S. Thomae Aquinatis"; Cardinal Sfondrato: "Innocentia Vindicata"; besides seven more apologists.

Some of the Angelic Doctor's neat sayings caught in familiar conversation have been preserved. "The poverty of a discontented religious is a useless expense." "The prayerless soul makes no progress whatever." "A religious without prayer resembles a soldier fighting without weapons." "Idleness is the devil's hook, on which any bait is tempting." "I cannot understand how anyone conscious of mortal sin can laugh or be merry." When asked how to detect a spiritual-minded man, he gave this reply: "He who is constantly chattering about frivolous things, who fears being despised, who is weary of life, whatever marvels he may work, I do not look on him as a perfect man, since all he does is without foundation, and he who cannot suffer is ready for a fall". To his sister Theodora, inquiring how to become a saint, he replied with a single word, "Velle," or "Resolve".

It is not surprising that one so clean of heart and full of charity should be favoured with visions, or that the dead should make an appeal to his pity. Thus, in earlier years he foresaw the triumph of the Mendicant Friars, while they were being subjected to persecution. "A Doctor of Theology in Paris, a man of great reputation and learning, and one who rendered signal services to the Church, during the time that the Master-General was doing battle for the order in the Roman Court, at the trying period when bitter enmity prevailed against the brethren, saw in a dream a great concourse of friars looking up to heaven, who called out to him; 'Look! Look!' He also gazed upwards, and saw these words emblazoned in letters of gold upon the sky: 'The Lord has delivered us from our enemies, and from the hands of all them that hated us'. At that very time the Brief issued by Pope Innocent against the Mendicant Friars was recalled by Alexander his successor, through the favour of the Most High" (Gerard de Frachet, "Lives of the Brethren," Book IV, Chap. xxiii.).

His deceased sister, Marietta, the Abbess of Capua, appeared to him in Paris in the year 1272, to commend her soul to his prayers: some time later she reappeared in Rome to tell him that she was admitted to glory. When he inquired about his dead brothers Raynald and Landulf she assured him that the former was already in paradise, but that the latter was still in purgatory. Then, emboldened, he put the question as to whether he would himself die before long, and secure his eternal salvation. To this she replied: "You will be saved, if you but persevere, but you will attain your last end very differently from us; you will speedily join us, but your glory will quite surpass ours". Shortly after this he was consoled by the vision of an angel displaying a book, on which the names of the saints were written in golden letters on an azure ground, and among them he saw Raynald's name among the martyrs. The angel disappeared, and Raynald stood visibly before him. "How do I stand with God?" was our saint's first question. "You are in a good state, my brother. Such a query is unbecoming, because you are in the sure way which leads to life. Hold fast to what you now have, and finish as you have begun: learn also for a certainty, that none of your Order, or very few, will be lost."

HIS WRITINGS; THIRD PERIOD: AND DEATH.

THE completion of the Moral Section of the "Summa" raised St. Thomas to the height of fame. The Universities of Paris, Bologna, and Naples, sent eager applications to have him, addressed to the General Chapter sitting in Florence during the Pentecost-tide of 1272. Rome lost him, as there was no reigning Pontiff to retain him, and Naples won him. The Capitular fathers assigned him to teach in Naples University, at the earnest suit of Charles, King of Sicily, the brother of St. Louis, who contributed two ounces of gold per month for his maintenance. Late in the month of August, Thomas quitted Rome in company with his brethren Reginald of Piperno and Bartholomew of Lucca.

All three fell sick of malaria at Cardinal d'Annibaldi's residence in the Campagna. Thomas speedily recovered, but his companions lay in grave danger of their lives, so, drawing from his neck a relic of St. Agnes, he applied it with his blessing, whereat they rose instantly in perfect health.

The home-coming of the Angelic Doctor to Naples was a veritable triumph. Five miles beyond the city he was met by princes, senators, professors, and the ever-clamorous youth of a University; an immense concourse of citizens filled the festive streets, roaring out their ovation, while the reverend magistracy conducted him to his convent of San Domenico Maggiore. Such demonstrations deeply wounded his humility: fortunately for himself his habitual recollection of thought kept him unconscious of the respectful salutions which greeted his every appearance in the public streets. Shortly after his arrival the Cardinal Legate of Sicily and the Archbishop of Capua, a former disciple, went to consult with him on matters of grave moment: on being informed of their arrival, the holy Doctor descended from his cell to the open cloister, but so rapt in thought that he passed them unnoticed. Presently his face brightened, and they heard him exclaim: "I have hit upon the solution I was looking for". The Cardinal looked shocked for a moment at the apparent discourtesy, until the Archbishop assured him that such moments of abstraction were priceless to the Church; then, pulling Thomas by the sleeve, he roused him from his reverie. Then only did the man of God observe them, and in simple language explained the mystery of his joyful mien. "It was merely because an excellent argument on a long-debated subject occurred just then to my mind, whose inner contemplation was expressed on my joyful countenance."

His end was close at hand, like a goal in sight; the words from the world behind the veil were vividly impressed on his memory: "You will speedily join us". In his cell he prayed and wrote, then passed forth to lecture in the University, in whose Aula Maxima he delivered the treatises of the Third Part of the "Summa Theologica," beginning with the Incarnation. The pulpit and chair from which he lectured were preserved for centuries after, together with his statue in marble in the outer atrium, where a marble slab bore this inscription

"Before passing in, pay reverence to this statue, and to the chair from which Saint Thomas pronounced so many oracles to a countless throng of students, for the glory and happiness of his age".

Every morning he said mass at an early hour in St. Nicholas Chapel, after which he heard another; he made his thanksgiving still vested in alb and girdle, but when he served mass, he resumed the black cappa. At the moment of consecration he used his favourite ejaculation: "Tu Rex gloriae, Christe. Tu Patris sempiternus es Filius". His Vesper hour of life had come, and he welcomed it: during the year 1273 his raptures became more and more frequent; seldom he went out, except to deliver the daily lecture. Now that the Commentary on Boetius was finished, his philosophic labours were ended. His pre-occupying theme now was the Sacred Godhead. As revealed in prophecy, it is the gist of his exposition of Isaiah: as revealed in the Incarnation and Redemption, it is the burden of the "Summa" in its concluding part. One night his friend and secretary, Reginald, who occupied the cell next to his, heard him talking in a loud tone as if engaged in animated conversation, which was the more remarkable since it was being carried on in time of profound silence. After a while Thomas came to his cell and bade him to get up. "Light the lamp, and bring the manuscript which I have begun upon Isaiah:" for a long space of time he dictated rapidly, then told him to retire again to rest. Reginald then threw himself upon his knees, and besought him to tell with whom he had been conversing. Finally, in God's dear name and in the name of their friendship, he adjured him to speak. "Dear son," replied the saint, "for many days past you have witnessed my affliction of spirit. I had misgivings over a passage in the text I have been commenting upon, so that I besought God with tears to give me understanding. Now this very night God has had compassion upon me, sending me His blessed Apostles Peter and Paul, who have brought me complete light. And now, in God's name, I command you to keep absolute silence as to this fact, during my lifetime." After the Commentary on Isaiah he wrote his Exposition of the first fifty-one Psalms. During the Lent of this year he preached every day in the Cathedral upon the words, "Hail full of grace, the Lord is with thee," giving a summary of Mary's rare privileges. The Compline hour at home filled him with the deepest devotion: tears coursed freely during the singing of the Lenten anthem: "Cast us not off in the season of our old age, when our strength shall fail us: Lord God, do not forsake us". As he was praying in the choir, he saw before him the figure of Father Romanus, to whom he had relinquished his chair in Paris. "Welcome indeed, dear brother," said he; "but when did you arrive here?" "I have passed from life," said the dead friar, "but I am permitted to appear on your account." St. Thomas was much overcome, but recovering self-possession, put these apt questions: "How do I stand with God, and are my works pleasing to Him?" "Thou art in a good state, and thy works are pleasing to God." "What then of thyself?" asked the holy Doctor. "I am in bliss," replied Romanus, "but have passed sixteen days in Purgatory." "Tell me then," cried Thomas, "how do the Blessed see God, and do our acquired habits abide with us in heaven?" "It is enough," answered Romanus, "if I tell you that I see God: ask me no more: 'As we have heard, so have we seen, in the city of the Lord of Hosts':" saying which he vanished. The Angelic Doctor at once gave voice to his conclusion: "therefore it is by specular vision that the Blessed see God".

The servant of God was permitted at times to penetrate men's hidden thoughts: one such instance was when he rebuked a friar for leaving the choir to indulge in gluttony. As he was pacing the terrace conversing with a nobleman, the devil appeared under the guise of a negro: "How dare you come here to tempt me!" he shouted as he advanced with clenched fist; whereupon the fiend vanished.

The year 1273 was drawing to a close when the pen dropped from his hand, before reaching his fiftieth year. It was on St. Nicholas Day, the 6th day of December, and in that saint's chapel, that he had a long ecstasy while saying Mass; what was then communicated to him he never revealed, but from that hour "he suspended his writing instruments," as William de Tocco puts it. Frequently he had been observed to be raised several cubits in the air, while engaged in prayer. Directly the treatise on the Eucharist was finished, some two months before this, Fr. Dominic di Caserta and other friars saw him thus uplifted in St. Nicholas Chapel shortly before Matins; but what filled them with awe was the miraculous voice proceeding from the mouth of the crucifix over the altar. "Thomas, thou hast written well of Me; what reward wilt thou have?" To which the holy man at once replied: "None other but Thyself, Lord ". Mid-way in the treatise of the Sacrament of Penance, after finishing ninety Questions, of five hundred and forty-nine articles, he lapsed into silence. To every appeal made by superiors or brethren there came the same reply: "I can do no more". Fr. Reginald, his secretary and confidant, urged him to resume his task. "Father, why do you leave unfinished this great work, which you have undertaken for God's glory and the world's enlightenment?" But he could only draw the reply: "I can do no more. Such secrets have been communicated to me, that all I have written and taught seem to me to be only like a handful of straw." Few could credit the report that the great oracle would speak no more; none imagined that the sun was setting, and in part already below the horizon. Nobly has Dante sung of him in his "Paradiso," Canto X

Such his wisdom upon earth,

Like to the Cherubim in lustre glowed.

. . . . . . . . . .

One of the lambs of that blest flock was I

Which Dominic so leads in righteous ways,

They thrive, unless they fall by vanity.

The "Summa Theologica" was his legacy to the Church. [A study of this monumental work has wrought many remarkable conversions, such as Rabbi Paul of Burgos, in the fifteenth century; Theobald Thamer, a disciple of Melanchthon; the Calvinist, Duperron, afterwards Cardinal and Archbishop of Sens. It has earned Luther's invectives, as well as Bucer's menace: "Take away Thomas, and I will destroy the Church".]

Fr. Reginald was obliged to feed him now, owing to his constant abstraction and frequent raptures. Before the Christmas festival St. Thomas spent a week with his sister, the Countess of San Severino, during which time they had but one long conversation, and that was about the joys of life everlasting. "What can have happened to my brother," she inquired of Reginald of Piperno, "that he is so entranced, and will not speak to me?" On his return to Naples he fell ill of fever; the attendant informed the prior that during the night he perceived a brilliant star enter by the window, and rest for a long time on the sleeper's head.

In obedience to Pope Gregory's summons to attend at the General Council of Lyons, which was to open on 1 May, St. Thomas quitted Naples on 28 January, 1274, taking with him by papal command his treatise "Against the Errors of the Greeks". He set out on foot, having for companions the trusty Reginald and another friar; so pre-occupied was he in thought, that, as they descended from Terracina along the Borgo Nuovo road, he struck his head violently against a fallen tree and lay stunned for some time. From that moment Reginald never left his side, but sought to occupy his mind by agreeable conversation. "Master, you are going to the Council on behalf of our order and of the kingdom of Naples." "God grant that I may see this great good accomplished," was the reply. "And furthermore," pursued Reginald, "they will make you a Cardinal, like Friar Bonaventure, so that both of you will be of great service to the Orders of which you are members." To this came the prophetic reply, confirmed by the event: "There is no state in which I can be of more use to my Order than that in which I am at present: rest assured that I shall never change my state of life". They halted for a few hours at Aquino; there he received a letter from the Abbot of Monte Cassino, soliciting his interpretation of a point of Rule, to which he returned a gracious reply. Owing to his failing strength, a mule was procured, upon which he rode to visit his niece, the Countess Francesca Ceccano at Maienza Castle. There he fell ill, and could take no food; it was now the season of Lent, and, since he would not break the law of abstinence, the doctor begged of him to say if there was any kind of food he could relish. "I have several times eaten in France a kind of fish called herring," said he; "but it is rare and very dear in these parts." His physician, John de Guido, sought vainly for the fish, until chancing to meet a fisherman coming from Terracina, he found some herrings at the bottom of a creel of sardines. Then Reginald coaxed him to eat some of the herrings. "From whence do they come?" asked the holy Master. "It is God who has sent them," was the reply; but all the same he would not partake of them, for fear of indulging in a delicacy. He tarried five days in Maienza Castle, and was able to say mass twice: the Abbot and some of the Cistercians from Fossa Nuova Abbey came to pay their respects. Thomas was now extremely ill, but persisted in fulfilling his obedience by proceeding onwards to the Council. Once more he mounted upon the mule, and the little party of ten moved slowly on to the Abbey, just seven miles away. Reverently they lifted him and carried him at his request into the church, for his last visit to the Blessed Sacrament: after a short prayer he was again taken up and carried through the cloisters to the Abbot's own apartments. Reginald had besought him not to quit Maienza Castle, where he could have every remedy and attention, but the saint would not listen to the proposal. "If the Lord wishes to take me, it is better that I should be found in a religious house than in the establishment of the laity." He entered Fossa Nuova Abbey on 10 February; as he was borne through the cloisters he uttered the saying of the Psalmist: "This is my rest for ever: here I shall dwell, for I have chosen it" (Psalm cxxxi. 14). The good Cistercians lavished every attention upon him, cutting and carrying faggots for the fire. "Whence comes this honour," he cried, in distress of humility, "that holy men should carry wood for my fire! Whence comes it that God's servants should wait upon me, and carry a burden so far, which must be painful to them!" Very speedily the tidings reached Naples that his dissolution was at hand; soon the Abbey was thronged with nobility and clergy and brethren, importuning to see him but once again. Among the Friars Preachers came his younger brother Rayner, who afterwards became Archbishop of Messina in Sicily. [The Bullarium Ordinis Praedicatorum, Tome II, gives him among the prelates promoted by Pope Honorius IV. "Frater Raynerius de Aquino, germanus frater Doctoris Angelici S. Thomae, Archiepiscopus Messanus, Messina in Sicilia." See also Bernard Guidonis, de Episcopis Sicilii Cavalerius, de Episcopis Ord. Praed., Tom. I, p. 46, no. cxxxv; Stephanus Sanpayo, ex. MSS. Archivii Caenobii Neapolitani S. Dominici.]

During an interval of the intermittent fever the Cistercians besought him to dictate an exposition of the Canticle of Canticles. "Give me St. Bernard's spirit, and I will do so," said he. Touched by their kindness, he complied: supported on his bed, he dictated the Commentary as Reginald read each succeeding verse, while eager hands committed it to writing. This, let it be observed, was his second exposition of Solomon's Song; it is entitled "Sonet vox tua," whereas the first is entitled "Salomon inspiratus ". This second work must be accepted rather as the fruit of his piety than of his learning. His biographer, William de Tocco, makes this observation on the fact: "It was fitting that the great Doctor, now about to be released from the body, should finish his teaching by the Canticle of Love between Jesus Christ and the faithful soul". The last words dictated were a passage from St. Paul, so fully realized in himself: "Our conversation is in heaven for in every place we are unto God the good odour of Christ". On coming to the eleventh verse of the seventh chapter -- "Come, my beloved, let us go forth into the fields," he swooned away, for his end was near. As the lamp of vitality was burning low, he received the last anointing after confessing to Fr. Reginald. The Abbot then brought him the Sacred Viaticum, while the brethren knelt around. Upborne in Reginald's arms the dying saint made this protestation of faith: "If in this world there be any knowledge of this mystery keener than that of faith, I wish now to use it to affirm that I believe in the real presence of Jesus Christ in this Sacrament, truly God and truly man, the Son of God, the Son of the Virgin Mary. This I believe and hold for true and certain. This faith is in my heart, and I profess it with my lips, just as the priest has pronounced it."

To Fr. Reginald it seemed impossible that St. Thomas should die thus early, when only entering upon his fiftieth year, so he used every art to rouse him, especially by dwelling on the great work which was before him in the coming Council, and of the sure honours which awaited him. Then with dying breath the holy Doctor made his last reply: "My son, keep yourself from harbouring any such thoughts, or from troubling yourself in this matter. What used to be at one time the object of my desires, is now a matter of thanksgiving. What I have ever been asking of God He now grants to me this day, in withdrawing me from this life in the same state in which it pleased His mercy to place me. Without a doubt I might have made further progress in learning, and have made my learning to be more profitable to others, by sharing with them what has been manifested to me. But the infinite goodness of my God has let me know, that if, without any merit of my own, I have received more graces and lights than other Doctors who have lived a long while, it is because the Lord wished to shorten the days of my exile, and to take me the sooner to be a sharer in His glory, out of a pure act of mercy. If you love me sincerely, be content and comforted, since my own consolation is perfect."

After receiving the Holy Viaticum he closed his eyes, and was silent for a short time, then repeated aloud his devout Rhythm:

Adoro Te devote, latens deitas,

quae sub his figuris vere latitas.

He uttered this Divine song to the finish, and yielded up his soul in the early morning of 7 March, 1274.