A National Science Foundation Research Experiences for Undergraduates Site

Department of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556

The presence of men, women, children and infants in the tombs (through all phases of the Early Bronze period) suggests that there may not have been significant vertical stratification at the site, that social status was inherited through family (see Bentley 1987, 1991), or that any stratification is primarily horizontal (Chesson 2001). The pattern of bones and pottery in the tombs suggests that the people followed a formal set of rules, and that the grave goods were intended to reflect and reinforce identity (Chesson 2001).

Bentley GR. 1987. Kinship and social structure at Early Bronze IA Bab edh-Dhra’, Jordan: a bioarchaeological analysis of the mortuary and dental data. Ph.D. disseration. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Bentley GR. 1991. A bioarchaeological reconstruction of the social and kinship systems at Early Bronze Age Bab edh-Dhra’, Jordan. In: Gregg S., editor. Between bands and states. Carbondale: Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University. p. 5-34.

Bloch-Smith E. 2003. Bronze and Iron Age burials and funerary customs. In: Richard S, editor. Near Eastern archaeology. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. p. 105-115.

Chesson MS. 2001. Embodied memories of place and people: death and society in an early urban community. In: Chesson MS, editor. Social memory, identity, and death: anthropological perspectives on mortuary rituals. Archaeological Publications of the American Anthropological Association 10:100-113. Arlington, VA: American Anthropological Association.

Esse DL. 1989. Secondary state formation and collapse in Early Bronze Age Palestine. In: de Miroschedji P, editor. L’urbanisation de la Palestine à l’âge du Bronze ancien. Oxford: BAR International Series 527 (ii). p. 81-96.

Gophna R. 1995. Early Bronze Age Canaan: some spatial and demographic observations. In: Levy TE, editor. The archaeology of society in the Holy Land. London: Leicester University Press. p. 269-280.

Hanbury-Tenison JW. 1986. The Late Chalcolithic to Early Bronze I transition in Palestine and Transjordan. Oxford: BAR International Series 311.

Ilan D. 2002. Mortuary practices in Early Bronze Age Canaan. Near East Archaeol 65:92-104.

Mazar A. 1990. Archaeology of the land of the Bible: 10,000 – 586 BCE. New York: Doubleday.

Philip G. 2003. The Early Bronze Age of the Southern Levant: a landscape approach. J Mediterr Archaeol 16:103-132.

Rast WE. 1999. Society and mortuary customs at Bab edh-Dhra. In: Kapitan T., editor. Archaeology, history and culture in Palestine and the Near East. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press. p. 164-182.

Rast WE. 2003. Archaeology of the Dead Sea Plain in Jordan. In: Richard S, editor. Near Eastern archaeology. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. p. 319-330.

Rast WE, Schaub RT. 1974. Survey of the southeastern plain of the Dead Sea, 1973. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan. 19:5-53.

Rast WE, Schaub RT. 1978. A preliminary report of excavations at Bab edh-Dhra’, 1975. In: Freedman DN, editor. Preliminary excavation reports: Bab edh-Dhra’, Sardis, Meiron, Tell el-Hesi, Carthage (Punic). Ann Am Schools Orient Res v. 43, p. 1-32.

Plants believed to have been grown during the Early Bronze Age at Bab edh-Dhra’.

From top to bottom: Emmer wheat, almonds, einkorn, olives, flax seed, grapes, figs & peaches.

Patterning of the tombs suggests that there may have been families with differential access to resources (Chesson 2001). Therefore, we see the assertion of individual identity (personal items), family identity (patterns of objects with multiple burials), and group identity (strict burial rules at the site) (see Rast 1999).

The site and cemetery are unique, as Bab edh-Dhra’ and Jericho represent the only two settlements with cemeteries dating to Early Bronze II –III (Ilan 2002, Philip 2003). This is particularly interesting given that the population was increasing and intensifying during this time of village florescence. Numerous artifacts are also associated with the tombs, including mostly local pottery. There are also goods with Egyptian and Syrian influence, suggesting that they are either imitative or imported.

Bab edh-Dhra’ represents a unique opportunity in the southern Levant to study both settlement and mortuary patterns at a time when the social landscape was changing dramatically as people moved into permanent, fortified villages.

Aerial view of the EB II-III charnel house excavations at Bab edh-Dhra’. From the Expedition to the Dead Sea Plain website: http://www.nd.edu/~edsp/babedhdrah.html

Bab edh-Dhra’, located on the southeastern shore of the Dead Sea, was occupied nearly continuously from the Early Bronze (EB) I through IV periods (Rast and Schaub 1978). The site is unique to this time in the southern Levant (an area encompassing Jordan, Israel and Palestine) due to the large cemetery located just south of the walled town.

In the EB IA (3150-3050 BC), inhabitants were agro-pastoralists, and most likely nomadic or semi-nomadic (Esse 1989, Mazar 1990, Rast 2003). The only evidence remaining of their existence is a vast cemetery containing thousands of shaft tombs and several artifacts; no settlement has been found dating to this period. The first permanent settlement at the site was constructed in the EB IB (3050-2950 BC) as an agricultural village (Hanbury-Tenison 1986).

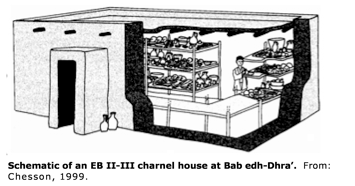

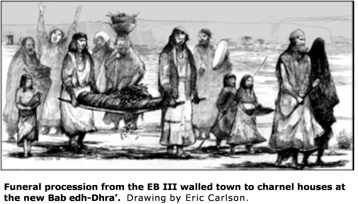

A fortified town was present by Early Bronze II, becoming a regional center by the Early Bronze III (2850-2300 BC) (Rast and Schaub 1974, Gophna 1995). Large, rectangular, above-ground communal burials (charnel houses) held up to 200 individuals in this period. During this time, a large wall was erected, approximately 7 meters thick.