Notre Dame Legends and Lore / by Dorothy V. Corson

When Margaret Clements told me about her uncle’s “Walk to Chicago,” I began researching the story. Among the items I found about the four students “Hikers” in the archives index files, was an essay written by Gerald Clements which appears near the end of this segment. It was published in The Scholastic on June 26, 1915, shortly after Gerald graduated on June 12, 1915. When I read it the first time, seven years ago, I could not help but liken it to poems and essays written by those soon to die in which the dead seem to be speaking to the living.

I was reminded of his essay and the irony of how he happened to write it, again, when I began preparing the “Walk to Chicago” story to go online in the Notre Dame Legends and Lore Web pages. When the story began to focus on Gerald, it seemed an appropriate place to share his essay -- as a link if nothing else -- but something kept holding me back. I was about to follow that old adage, “When in doubt don’t,” when in rereading his essay about war, it recalled to my mind a memory from my childhood. A framed poem on the wall in my father’s home office had a small oval inset photograph of a soldier in the lower right corner. I’m sure that from time to time I may have inquired about it, but only one other thing about it remains clear. It was a photograph of an uncle I had never known who died at Vimy Ridge in France during World War I. I also remembered the poem had something to do with poppies in “Flanders Fields.”

Wanting to know more about it drew me to the Internet to see what I could find with just these two pieces of information. Eureka, first time out, I found the poem. “In Flanders Fields,” along with the story behind how it was written.

The Web site I was drawn to, “The First World War -- The Heritage of the Great War 1914-1918,” had this information about the poem and they very kindly allowed the use of anything on their site. The following information was just what I was looking for:

By Rob Ruggenberg

John McCrae’s (picture left) “In Flanders Fields” remains to this day one of the most memorable war poems ever written. It is a lasting legacy of the terrible battle in the Ypres salient in the spring of 1915.

John McCrae’s (picture left) “In Flanders Fields” remains to this day one of the most memorable war poems ever written. It is a lasting legacy of the terrible battle in the Ypres salient in the spring of 1915.

The most asked question is: why poppies?

Wild poppies flower when other plants in their direct neighbourhood are dead. Their seeds can lie on the ground for years and years, but only when there are no more competing flowers or shrubs in the vicinity (for instance when someone firmly roots up the ground), these seeds will sprout

There was enough rooted up soil on the battlefield of the Western Front; in fact the whole front consisted of churned up soil. So in May 1915, when McCrae wrote his poem, around him poppies blossomed like no one had ever seen before.

It is also possible that in this poem the poppy plays one more role. The poppy is known as a symbol of sleep. The last line We shall not sleep, though poppies grow / In Flanders fields might point to this fact. Some kinds of poppies can be used to derive opium from, from which morphine can be made. Morphine is one of the strongest painkillers and was often used to put a wounded soldier to sleep. Sometimes medical doctors used it in a higher dose to put the incurable wounded out of their misery.

Flanders is the name of the whole western part of Belgium. It is flat country where people speak Flemish, a kind of Dutch. Flanders (Vlaanderen in Flemish) holds old and famous cities like Antwerp, Bruges and Ypres. It is ancient battleground. For centuries the fields of Flanders have been soaked with blood.

‘In Flanders Fields’ is also the name of an American War Cemetery in Belgium, where 368 Americans are buried. This cemetery is situated near the village of Waregem, quite a distance from the place where McCrae actually wrote his poem. The cemetery got its name from the poem though. The bronze foot of the flag-staff is decorated with daisies and poppies.

Another reference to the poem can be found on the Canadian Memorial at Vimy, in Northern France. Between the pylons, at their base, is a sculpture of a dying soldier throwing his burning torch to his comrades -- obviously referring to the last verse of the poem.

John McCrae’s poem may be the most famous one of the Great War -- sometimes only the first two verses are cited or printed. Nevertheless I will give you the full and exact version of McCrae’s great poem, taken from his own, handwritten copy. But first, here is the story of how he wrote it -- and how the recent death of a dear friend moved him:

Although he had been a doctor for years and had served in the Boer War in South Africa, it was impossible to get used to the suffering, the screams, and the blood here, and Major John McCrae had seen and heard enough in his dressing station to last him a lifetime.

As a surgeon attached to the Canadian 1st Field Artillery Brigade, Major McCrae, who had joined the McGill faculty in 1900 after graduating from the University of Toronto, had spent sixteen days treating injured men -- Canadians, British, Indians, French, and Germans -- in the Ypres salient.

It had been an ordeal that he had hardly thought possible. McCrae later wrote to his mother:

‘Seventeen days of Hades! At the end of the first day if anyone had told us we had to spend seventeen days there, we would have folded our hands and said it could not have been done’

One death particularly affected McCrae. A young friend and former student, Lieut. Alexis Helmer of Ottawa, had been killed by a shell burst on 2 May 1915. Lieutenant Helmer was buried later that night in the little cemetery (called Essex Farm), just outside McCrae’s dressing station. McCrae had performed the funeral ceremony in the absence of the chaplain, reciting from memory some passages from the Church of England’s ‘Order of Burial of the Dead.’ This had happened in complete darkness, as for security reasons it was forbidden to make light.

The next morning, sitting on the rearstep of an ambulance parked near the dressing station beside the Yser Canal, just a few hundred yards north of Ypres, McCrae vented his anguish by composing a poem. The major was no stranger to writing, having authored several medical texts besides dabbling in poetry

The next morning, sitting on the rearstep of an ambulance parked near the dressing station beside the Yser Canal, just a few hundred yards north of Ypres, McCrae vented his anguish by composing a poem. The major was no stranger to writing, having authored several medical texts besides dabbling in poetry

In the cemetery (see the drawing right by Edward Morrison), McCrae could see the wild poppies that sprang up from the ditches and the graves, and he spent twenty minutes of precious rest time scribbling fifteen lines of verse in a notebook.

A young soldier watched him write it. Cyril Allinson, a twenty-two year old sergeant-major, was delivering mail that day when he spotted McCrae. The major looked up as Allinson approached, then went on writing while the sergeant-major stood there quietly. ‘His face was very tired but calm as he wrote,’ Allinson recalled. ‘He looked around from time to time, his eyes straying to Helmer’s grave.’

When McCrae finished five minutes later, he took his mail from Allinson and, without saying a word, handed his pad to the young NCO. Allinson was moved by what he read:

‘The poem was an exact description of the scene in front of us both. He used the word blow in that line because the poppies actually were being blown that morning by a gentle east wind. It never occurred to me at that time that it would ever be published. It seemed to me just an exact description of the scene.’

Allinson’s account corresponds with the words of the commanding officer at the spot, Lieutenant Colonel Edward Morrison. This is how Morrison described the scene:

‘This poem was literally born of fire and blood during the hottest phase of the second battle of Ypres. My headquarters were in a trench on the top of the bank of the Ypres Canal, and John had his dressing station in a hole dug in the foot of the bank. During periods in the battle men who were shot actually rolled down the bank into his dressing station. Along from us a few hundred yards was the headquarters of a regiment, and many times during the sixteen days of battle, he and I watched them burying their dead whenever there was a lull. Thus the crosses, row on row, grew into a good-sized cemetery. Just as he describes, we often heard in the mornings the larks singing high in the air, between the crash of the shell and the reports of the guns in the battery just beside us.’

The poem (initially called We shall not sleep) was very nearly not published. Dissatisfied with it, McCrae tossed the poem away, but Morrison, [his commanding officer], retrieved it and it was later published in Punch on December 8, 1915.

-- Rob Ruggenberg

|

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

We are the Dead. Short days ago

Take up our quarrel with the foe: |

Reading the above poem, recalled to my mind that Joyce Kilmer had also written a poem for his fallen comrades shortly before he was killed in action on July 30, 1918, near Ourcq in France. He was buried beside a stream that bears the same name. He is best known for his poem, “Trees.”

The Scholastic recorded these thoughts and these lines from his poem written for his fallen comrades before his own death: “How applicable to himself are the concluding lines of his ‘Rouge Bouquet’ poem: ‘Comrade true, born anew, peace to you / Your souls shall be where the heroes are / And your memory shine like the morning star.’

It seems that war poems and essays in which the dead speak are not all that rare. Even Kipling did it.

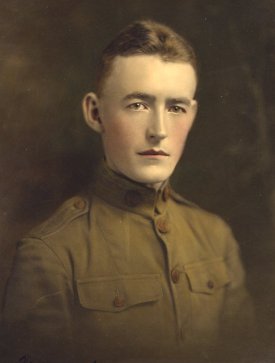

Meanwhile, a world away from Major John McCrae -- that same Spring of 1915 -- Gerald Clements was preparing for his graduation just weeks away, on June 12, 1915. He was also about to become a partner in his father’s successful law firm when he wrote his essay. Perhaps, moved by the news of the recent horrific battles in France that same Spring of 1915, he put his pen to paper before leaving the campus, to record, with heartfelt sincerity, his essay about the futility of war for the school publication.

Looking back it also seems ironic that two years after writing this essay, “he exhibited a single-minded determination to enlist in the Army,” as soon as World War I was declared by the United States. He did not live to see the history he wrote about repeated in the years to come. I will let the reader draw his/her own conclusions about the essay that follows:

THROUGHOUT all the long ages since men first formed themselves into organized society, down to the present time, war has been an established institution. Men and nations have built and burnt, have saved and slain, have oppressed and resisted oppression, men have poured out their blood on the field of battle, their bones have bleached on the plains and mingled with the dust of centuries that have passed over them, and all because of war, the fierce desire for martial triumph and the glory of conquest. Without doubt many of the wars of the past have been just, and on the battlefields of history man has struggled against man, each supremely confident in the belief that his was a fight for principle, that upon his side lay justice and right. And when the men of the nation have marched down to the field of battle to do and die for the eternal principles of freedom and liberty, who is there to say that theirs was not the cause of justice?

But while men are justified in the use of force as a last resort in resistance to oppression, and while even in an unjust war each side may believe itself to be right, yet, I say that the practice of settling disputes between nations by means of trial by battle, which has resulted in ceaseless conflict since the dawn of history, is absolutely opposed to the moral nature of man. First, because it is an irrational method of settling differences between rational beings; and second, because it is inconsistent with the true underlying spirit of Christianity.

When differences as to personal and property rights arise between individuals, the just and reasonable man carries his grievance to the law, and laying his cause before the bar of justice, demands that his rights be vindicated. He does not seek blood as a compensation for the violation of his rights. He realizes the futility of attempting to adjudicate a legal right by means of personal combat, and has long since cast aside the delusion that the duel is a just method of settling purely personal difficulties. How comes it, then, that on the occasion of a serious disagreement between nations, rational methods of adjudication are cast to the winds and forgotten? Force may be lawfully used as a last possible resort for the settlement of disputes, but as a matter of fact it has usually been the very first which the nations have had recourse. Instead of being the most extreme measure to be used for the protection of national rights, it always has been and seems to be now, kept ever in readiness as the first-hand adjudicator of international difficulties. The nations are composed of men who would abhor the thought of adjusting their private differences by personal combat, except as the only possible means of protecting themselves. But men seem to forget that as a nation they are but a collection of individuals and that the principles which apply to their relations with one another obtain just as truly between themselves as a nation and other nations.

Reason demands the settlement of justice between nations just as much as between individuals, but you might as well entrust the fate of nations to the turn of a wheel or a roll of the dice, as to expect justice to arise out of the smoke and blood and chaos of battle. Justice is a matter of mind not of muscle; and for men to expect that a just and equitable settlement of international questions can be reached through the overpowering force of a million troops, or the keenness and foresight of a strategic leader, is as vain a delusion as ever clouded the human brain. To the victor belong the spoils, and the spoils of war are garnered by the mighty and the favorites of fortune.

War not only fails to settle disputes justly, except in cases of rare coincidence, but it also fails to settle them with any degree of permanency. War is rather a perpetuation of difficulties. It is the endless turnstile of history. Nations are conquered, treaties are made, each sanctioning the result of the last, and the nations are said to be at peace. But beneath these seemingly placid and calm waters of reconciliation there flows a strong and fiercely boiling undercurrent of hatred and a longing for revenge. It is the lex talionis, the law of “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth,” and the conquered nation is no sooner compelled to submit to terms of peace imposed by the victor than forthwith it sets itself to make ready against the day when with all the grand wild glory and pomp of martial force, it may once more proceed against its ancient enemy to reclaim the spoils of war. To-day we are witnessing the fulfillment of a prophecy which the great international thinkers of the world have long been making. We are beholding a world war; and the questions which men hope will be settled by this great conflict, are but the same questions over which other men have died, and concerning which other treaties have been made. Two of these I shall mention.

When the ruthless hand of the “Iron Chancellor” shattered the second empire of France and tore from her grasp the fairest of French provinces, a treaty was made over these provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, that there would be no more war. But it was not to be. Beneath the treaty of 1870 the flames of enmity smoldered, until a few months ago, war was again declared, and Frenchmen are now dying that the tricolor may once more wave over their beloved Alsace and Lorraine. They are fighting over a question which fifty years ago was believed to have been permanently settled.

The other question which I shall mention -- a readjudication of which is being sought in the present war -- is the centuries old struggle of Russia for an outlet to the sea. The frozen and icebound harbors of the Baltic afford but poor egress to the world for the great Eastern Empire, and she has long been trying to secure for herself passage to the Mediterranean through the Black Sea and the Dardanelles. England, France, Turkey and Russia have struggled over this very question, and treaties have been made settling the matter, as it was then thought, but to-day the waters of the Dardanelles run red with the blood of the Teuton and the Frank, the Briton and the Turk. The matter is not yet settled, nor will there be an end to the dispute arising from this question, even if Russia is successful in her effort to force her way. The resting-place of nations is not yet reached. The control of Constantinople and the Dardanelles by Russia means that the Indian possession of England will be in constant danger. And the lion of England will never allow the great bear of the North to creep down into Asia, and threaten the rich and wonderful land of India. The occurrence of such an event, -- and it is perfectly in line with the present trend of international affairs, -- can mean only another great upheaval of the world powers. England and Russia will engage in a war to the death, and the flames of Hell will once more sweep over Europe, blood-soaked with the wars of centuries.

Here we have concrete examples, absolutely up to date, of the inefficiency and failure of war as a just, politic and permanent adjudicator of international questions. War is but the ceaseless treadmill upon which nations of the world have been forever tramping, tramping, tramping, always in the vain hope that the time may come when by conquest and force of arms the nation will have been made all-powerful, its people wealthy, and its government everlasting.

With the coming of the Redeemer, the rise of Christianity, and the spreading power of the Pope and Christian princes, one might have thought these vain struggles for gain and glory would be no more. True, the Popes of the Middle Ages established the Truce of God, and time and again offered mediation to the warring principalities, but to bring these rough and ready men of feudal times to a realization of the folly of forage and war was a task too great; and now despite the fact that this is the Twentieth century of the Christian era, justice is still driven from the highest places, still there is in vogue the antique trial by battle, as vain and foolish as the primitive ordeal by fire, and still the warring crowns of Europe call upon the God of the universe to prosper them in their senseless struggles for national and territorial domination.

The true Christian attitude was expressed in the words of that saintly pontiff, Pius X., when shortly before his death he was approached by the Austrian envoy with the request that the papal benediction be bestowed upon the arms of Austria. He refused, saying: “I will bless nothing but peace.” And these few words express the real, true spirit of Christianity.

The most we can say for ourselves is that Christianity has entered gradually the life of the individual, and in many ways ennobled and purified it, that we hope for the growth of its influence through the centuries, and that someday the thoughts of men and nations in regard to war will be regulated by the Sermon on the Mount. There is no more reason why the mind should be shocked by the evils of war than by many other evils. We shall not get forward by an excess of horror, by emotional exaggerations, by fostering illusions. We shall advance not by ignoring the past, but by reasoning and building upon it, and by cherishing a Christian faith which does not evade or color facts, but helps us to work patiently with the material of reality.

--Gerald Samuel Clements LL. B.

My father, Willam Buckles, also served in the Royal Canadian Mounted Rifles from April, 1916 until November, 1918. The poem, “In Flanders Fields” remained on his office wall all his life. He rarely talked about his war experiences – I found out about them recently when I read his trench warfare diaries.

He kept them from the day he went into the service on March 13, 1916 until he was discharged on November 6, 1918. On that day in his diary he wrote “Discharge 10 a.m. Good bye Army!” On November 7 there is written only one word “Home.”

He was wounded in “No Man’s Land” trying to get a buddy to an aid station (he had already expired). Blood was gushing from his arm and upper body and he could no longer crawl to safety. He knew he would be an easy target, but desperate, he stood up, and ran instead. And he survived, or I would not be here to tell his story.

In his office he also had a composite photograph of himself -- in the uniform of the Royal Canadian Mounted Rifles -- together with his two sons, Ken and Bill, in U. S. Army uniforms, all at age 21, in three different conflicts. I know now why that poem was always there -- to remember his brother -- and all those less fortunate, who did not survive, who gave their lives that others might live in peace and freedom.

When I’ve finished my Grotto mission my next mission will be to transcribe his World War I trench warfare diaries and compile his cartoon postcards, photographs and memorabilia from World War I.

Dorothy V. Corson

April 5, 2003