It all began . . . one summer night in mid-July in the year 1979. An ordinary evening, or so it seemed at the time. My family was spending our usual evening at home (our son, my husband and myself) when the telephone rang and my husband answered it with: “It’s for you,” and he handed me the phone.

My new telephone friend and I usually always talked privately during her daytime shop hours -- she and her husband owned a small gift shop -- so I was surprised and a bit alarmed that she might have another health problem when I picked up the phone.

She immediately allayed my fears, knowing her unexpected timing might concern me. “Dottie, everything is all right and I donít want to keep you from your family, but I have something very interesting to share with you, and a favor to ask, would you call me first thing in the morning? Or better yet, could you spare the time to come over to the shop, I have something unusual to show you?”

Intrigued, I assured her I would call but because of an appointment I’d have to stop by another time. “Perfect, that part will keep for another day,” she said, “but I’ll be looking forward to hearing from you.”

I was still curious, the following morning when I returned her call. “Do you remember, Dottie, several weeks ago, when I told you of my sudden interest in sketching,” she asked? I did recall it, remembering her telling me how desperately she had been searching for something to take her mind off her second bout with cancer.

I was still curious, the following morning when I returned her call. “Do you remember, Dottie, several weeks ago, when I told you of my sudden interest in sketching,” she asked? I did recall it, remembering her telling me how desperately she had been searching for something to take her mind off her second bout with cancer.

She had told me that she was sitting at her desk one day doodling when she had the sudden impulse to draw, something she had never done before. She sketched a picture of a goat out of a magazine and then looking out the window sketched the house across the street. Later her husband stumbled upon them and in inquiring about them was surprised to learn that she had done them. “Not bad,” he said, “in fact very good for a beginner.” And he went on to say, “You know in a few years I’ll be retiring and we may have to close the shop. It would be nice if you had something to take its place. You really should consider taking some art classes.” Hearing her husband’s spontaneous praise she said she warmed with pleasure and really began seriously considering the possibility of doing just that. In the meantime, she continued to sketch whenever the mood came upon her, enjoying it more and more.

She then began to relate to me this most unusual incident that had prompted her evening telephone call. Her son, an ornithologist and professor at a western university -- deeply into the study of the migration of birds -- had come home for a few days for a summer visit. My friend had a lapidary shop which they called NATURE GEMS and she had arranged to close it for several days to be with her son and his family. She and her husband took them for an afternoon drive into Michigan and they were taking in the many antique shops along the way. In a dusty corner of a cluttered garage antique shop in Edwardsburg, Michigan, her husband came upon what appeared to be an old photo album.

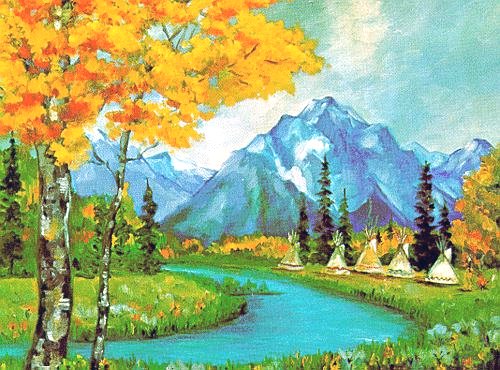

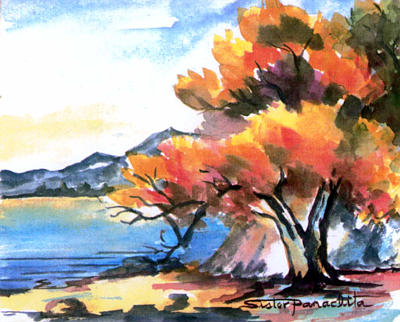

In it, were odds and ends of doodles, postcard sized watercolor and oil paintings, and other bits of artwork, as well as a few photographs. His wife and daughter-in-law were at the counter each considering small paintings that appeared to be by the same artist. Calling her over to it, he flipped through it quickly and suggested she might like to have it to spark her newly awakened interest in sketching.

In it, were odds and ends of doodles, postcard sized watercolor and oil paintings, and other bits of artwork, as well as a few photographs. His wife and daughter-in-law were at the counter each considering small paintings that appeared to be by the same artist. Calling her over to it, he flipped through it quickly and suggested she might like to have it to spark her newly awakened interest in sketching.

She said she felt inspired and encouraged just leafing through it and knew at once she wanted it. It just seemed to say, “Take me Home.” She said she felt so sad to see it there, unloved, in the midst of all that clutter. Like seeing a lost and lonely little puppy with no one to love it. She said she just had to take it home and take care of it herself. Her husband bargained with the antique dealer and they took it away feeling they had found a little treasure no one else had recognized. With the rush of having company and a little one under foot, they decided to look at it more thoroughly after her son and his family were gone and when they got home put it away in a drawer for safekeeping.

Her son had left the day before. She said the evening she called me, she was clearing the dinner table while her husband took the album from its place of safekeeping and sat down to view it more closely. Seconds later he motioned to her to sit down and view it with him. Upon closer examination, to their wonder and surprise, they discovered it to be the personal album of a Sister Paraclita, a Holy Cross Native Amercan nun, complete with photographs and articles about her and her paintings. Her obituary and the date of her death were marked on several photographs so it was assumed that perhaps another nun, or Sister Paraclitaís Superior, had finished it after her funeral. But if so, the mystery was how it wound up in an old antique shop in Edwardsburg, Michigan?

My friend was not only uplifted and encouraged by the paintings and sketches, many more than she had noticed as she flipped through it at the antique shop, she was also fascinated by this Indian nun. We found out later, she was the only Native American Indian nun in the Holy Cross order at that time. She was so buoyed in spirit in viewing her album that she said she felt the spirit of Sister Paraclita was encouraging her own budding artistic talents during her latest serious bout with cancer. She could not have known it then, but they also shared a kinship with suffering, because it was later learned that Sister Paraclita, herself, had also suffered from cancer for many years before her death.

Interestingly, I have since learned that Sister Paraclita had a special devotion to the Holy Spirit and that her name comes from Paraclete, meaning the Holy Spirit; the Comforter. From Greek parakletos advocate; (literally) one called to aid, to comfort and console. Or paraclete, a friend, advocate , or comforter. Which were just the feelings my friend felt emanating to her from the album.

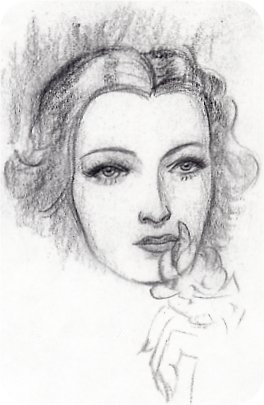

Sister Paraclita grew old in the several photographs in the album, from a slim fresh-faced young nun to a plump sweet-faced matronly Sister. Exhilarated by her find, my friend said she couldnít resist her spontaneous evening phone call to me. She knew I made weekly visits to my Sister friends at the Holy Cross Convent on the Saint Mary’s campus, and felt I might be able to help her find out more about Sister Paraclita’s album and how it wound up in a cluttered garage antique shop.

Sister Paraclita grew old in the several photographs in the album, from a slim fresh-faced young nun to a plump sweet-faced matronly Sister. Exhilarated by her find, my friend said she couldnít resist her spontaneous evening phone call to me. She knew I made weekly visits to my Sister friends at the Holy Cross Convent on the Saint Mary’s campus, and felt I might be able to help her find out more about Sister Paraclita’s album and how it wound up in a cluttered garage antique shop.

With her own budding interest in art just emerging my friend said she became caught up in learning more about this Indian nun whose artwork had somehow mysteriously landed in her lap. And by curious coincidence our own spiritual friendship, hers and mine, had come about some years before through just such a providential encounter.

Since her small shop absorbed most of her daytime hours, she called me to tell me the story and ask a favor of me. “Could I, and would I mind, asking about Sister Paraclita at the convent?” She was fascinated by her, she said, “and any scrap of information about her would please me very much.” My friend had already enrolled in a university art course and she said she had put her two favorite photographs of Sister Paraclita in the lid of her paint box so she went with her wherever she painted. “People will probably think I’m balmy,” she said, “but somehow I feel warmed and encouraged by her spirit. A tiny pinpoint of light seems to be illuminating the darkness of this disease I’m fighting, filling me with a warm, light, and peaceful feeling, I haven’t felt in a long time.”

Intrigued, myself, having once been an artist, I joined her at her shop the next day and found myself just as taken with this mysterious collection of fascinating sketches. Nuns in a wartime jeep jostling over a bumpy road. Flowers of every description were doodled on what appeared to be scraps of paper (frugally kept for that purpose perhaps). Small paintings of a man and a woman in uniform and numerous thumbnail postcard-size watercolors of mountainous scenes. As well as, articles and photographs, and her obituary. Towards the end were several blank spaces where my friend explained there had been a half a dozen small oil paintings the antique dealer had taken out and sold separately.

“Let me do some checking among my sister friends,” I told her, “and Iíll get back with you as soon as I have more information about her.” My own presence at Saint Mary’s had been due to some most unusual and inspiring circumstances (a story in itself) and began when a Sister I had corresponded with in Redwood City, California had been retired to the mother house at Saint Mary’s. I became acquainted with Sister Bertha through writing letters to her for Father Jankowski during his last days at Holy Cross House on the Notre Dame campus. It was Father Jankowski, CSC, who was the pastor of St. Stanislaus Church at the time, who built a replica of the Notre Dame Grotto at his parish church in 1962. When Sister Bertha returned to Saint Mary’s she asked me to visit her there and we renewed our letter friendship in person.

“Let me do some checking among my sister friends,” I told her, “and Iíll get back with you as soon as I have more information about her.” My own presence at Saint Mary’s had been due to some most unusual and inspiring circumstances (a story in itself) and began when a Sister I had corresponded with in Redwood City, California had been retired to the mother house at Saint Mary’s. I became acquainted with Sister Bertha through writing letters to her for Father Jankowski during his last days at Holy Cross House on the Notre Dame campus. It was Father Jankowski, CSC, who was the pastor of St. Stanislaus Church at the time, who built a replica of the Notre Dame Grotto at his parish church in 1962. When Sister Bertha returned to Saint Mary’s she asked me to visit her there and we renewed our letter friendship in person.

My first inquiry upon arriving at the convent office led me to Sister Faith who was tending the telephone in Bertrand Hall, and graciously offered to talk to me. She had been out west with Sister Paraclita and had one of her paintings in her room she promised to show me.

Since, that initial first interview, Sister Faith has become, this past 12 years, a dear and valued friend. She said she had gone with Sister Paraclita many time into the Wasatch mountains in Utah where she made rough thumbnail sketches to be made into finished paintings in her studio. She said she had always marveled at her bright colorful sketches and her spontaneous rapid sketching, anytime, anywhere. That the Sisters were always delighted with the place card sized artwork she regularly passed out to them.

Sister Faith made a date with me to show me her own painting by Sister Paraclita on my next visit, and she explained how rare it was to own one as every painting Sister ever did she gave away to friends or to Sisters as gifts for their friends. So that few were in the Convent and most were scattered across the country. She was puzzled about the album, too, and became as absorbed with the mystery of how it came to be in an antique shop as I had been. And it was she who gave me my next name to follow up.

After my brief visit with Sister Faith, I proceeded to Sister Bertha’s room for our usual weekly visit. To my wonder and surprise, I soon learned that Sister Bertha was also a good friend of Sister Paraclita and had twice returned to the Indian reservation with her, as her companion, on her home visits. I’m sure now, that had I seen Sister Bertha first, I might never have met Sister Faith and been put on the trail, like a bloodhound, looking for fresh clues to the mystery. Once on that trail, I couldn’t stop wondering about it. Like an absorbing mystery novel, one just can’t put it down until it’s finished.

Sister Bertha proceeded to relate many delightful remembrances of Sister Paraclita. She told me about her home visits with her, and how she got to know her Indian parents on the reservation she called home. She especially recalled a picnic they went on, under a tree, beside a lake, the roasted sweet corn and the fresh strawberries they picked. Sister Paraclita was very neat, Sister Bertha said, and loved to make desserts and candy, especially fudge. Her father, she said, was an Indian Chief and a prince of a fellow, his father an Indian scout, and both mother and father were most welcoming to her.

She then related how Sister Paraclita had told her of how she and her sister, as young girls, were brought to the Sisters at St. Mary’s Academy in Salt Lake City by their father, a non-catholic, to be educated. From that experience she decided to become a nun and Eula Catherine Cosgrove became Sister Paraclita (her Indian name was Butterfly, which interestingly is also symbolic of the spirit). She was born April 5, (coincidentally, also my birthday), in 1904 in Fort Hall, Idaho and lived in Blackfoot, Idaho. Her father was prominent in tribal affairs for the Shoshone and Bannock Indians at Fort Hall. Sister Paraclita was a member of that tribe.

Sister Bertha, herself, has also been a delightful friend to me, a warm and welcoming company-keeper and our friendship has been a blessing to both of us.

From that time on every Sister I met in the hallways and elevators I would ask if they knew Sister Paraclita and found many who were eager to talk to me about her. Sister Faith’s visit led me to Sister Sylvester who relived her cross country train trip with her, when Sister Paraclita accompanied her to her own home in New York. She said Sister Paraclita had a thing about cleanliness and always carried plenty of soap in her suitcase. Each name led to another until I could almost write a book of the stories I collected about her. The more I got into it the more of an adventure it became. Still, I found no one who could explain the album. So, to spark interest in learning more about her I made arrangements with my friend, Jenna, to bring the album to the convent for the Sisters to view, hoping to find someone new from whom to make inquiries. When the day arrived to display the album in the convent community parlor we were both surprised to find the contents of the album -- aside from the few which could not be lifted off the sticky paper without damage -- amounted to more than a library table full of her work. The Sisters were astounded, and equally puzzled, never having seen that much of Sister Paraclita’s work in one place before.

As the months passed, though I collected bits and pieces of stories from those who had known Sister Paraclita, still I was no closer to solving the mystery. Then one day, I met a newly arrived Sister who worked in the campus print shop and also designed jewelry as a hobby. In telling her the story about my friend’s lapidary shop she was most interested. As much to see the sketches as to see my friend’s shop where they too made jewelry from natureís stones. From turquoise to jade to endless polished stones.

So, one day I made arrangements with my friend, Jenna, for this newly arrived sister to view her shop and the sketches. She, herself, had taken over one of Sister Paraclita’s posts as an art teacher out west so she had known her briefly and was most interested in seeing more of her art.

So, one day I made arrangements with my friend, Jenna, for this newly arrived sister to view her shop and the sketches. She, herself, had taken over one of Sister Paraclita’s posts as an art teacher out west so she had known her briefly and was most interested in seeing more of her art.

The day of our visit was balmy and sunny, a perfect day to acquaint my two friends with one another. Jenna had spread the contents of the album in a small side room off her shop, where the Sister could view them all together. By this time, her husband had removed a good many of the drawings from the album fearing their continued presence on the sticky pages might cause them to deteriorate. At first, I was disappointed that the sequence of the album had been disturbed, but then I learned that when the sketches were removed parts of letters were on the other side of the drawings. At a casual glance, our first assumption, was that being thrifty she might have used the backs of old letters as sketching paper. A more careful study later, revealed some interesting new observations.

The Sister studied the drawings that had already been removed and those remaining in the album, and casually commented on how unusual it was for any of Sister Paraclita’s work to be seen in such numbers. Anxious to view Jenna’s shop, the stones and jewelry there, because that was her special interest, she made a parting comment to me as the two of them moved back into the shop. While I went about reordering the album -- her passing comment reverberated in my thoughts. “I’m sure this is not Sister Paraclita’s album,” she said, “because it wouldn’t be in keeping for a nun to keep her work in this way, most especially, Sister Paraclita, who was known for giving away all her paintings and keeping none for herself.” Without knowing it, her casual comment had put an entirely new light on the subject for me. It hadn’t occurred to me, before her comment, that the album didn’t belong to Sister Paraclita.

So while they were busy exchanging mutual interests and the shop’s contents, I began to peruse the album pictures once again from this new perspective. Okay, if it wasn’t Sister Paraclita’s own album -- then whose?

Once the drawings had been removed, much of the artwork appeared to be sketched on the backs of old letters and a few of the sketches were personalized with the name Irvin. At first I thought they might be her letters to a soldier that had been returned to her when he died after which, frugally, she had used the backs of them to do rough sketching. Now I began to conclude that perhaps the album was not hers but belonged to the person referred to in the few more complete portions of letters that were in it (pieces of the letters, I should say, as some had only a few lines on the backs of the sketches).

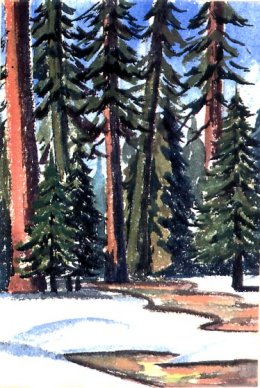

One notecard-sized painting of pine trees (pictured), which at first seemed to be only a single sheet, turned out to be a notecard with its pages stuck together. In carefully separating it, the only complete note in the album was discovered. It could easily have been missed because her small painting covered the entire front of it.

One notecard-sized painting of pine trees (pictured), which at first seemed to be only a single sheet, turned out to be a notecard with its pages stuck together. In carefully separating it, the only complete note in the album was discovered. It could easily have been missed because her small painting covered the entire front of it.

Inside, was a note from Sister Paraclita to Irvin dated, May, 1953. A man with the name of Cosgrove (probably her brother) was mentioned in it. He was coming to pick up Sister Paraclita and her companion (most likely my friend Sister Bertha) for her home visit at the reservation. Later, when I was able to obtain his address, I wrote to him but received no reply. He may have been deceased or my address was too old.

I began, systematically, to study each sketch taken out of the album that appeared to have pieces of letters on the back, surprised to find this almost whole thought capsuled in the several lines of script written in purple ink on the reverse of one sketch:

“My what a shock-- the President’s death. We could scarcely believe it and it seemed a personal loss. We remained up later than usual that night listening to the broadcasts.”

All of which dated the letter to President Roosevelt’s death in 1945. At that moment the realization hit me, she had not used the backs of letters for sketching but rather, in this new light, I could see that the letters must have been hers to someone else, and each letter she had decorated with some floral or decorative motif as one would find in stationery stores today. The drawings on the letters were carefully cut out and attached to the sticky pages in the album, along with the postcard-sized paintings she included in her letters.

Once the author of the letters was established, I began to search in the writing on the reverse sides of the decorated stationery looking for more clues to identify the recipient of Sister Paraclita’s letters and drawings. The name Irvin (the same name that personalized a couple of the sketches) seemed to pop up in enough of the writing in the letters to indicate that he must be the one to whom the letters were being sent.

Two drawings, of a young man and a young woman in uniform, also established a wartime segment of the album. On the back of one of the drawings that had been pasted in the album were these almost complete sentences, written by Sister Paraclita, in her very distinctive hand, and again in purple ink:

Knowing I was finally on to something but not wanting to reveal my direction until I had more to go on, I did not mention anything to Jenna, having in mind that it was a story worth writing about and not wanting to spoil the ending. Since the Sisterís comment had just been in passing, I doubted she even realized the significance of her observation to me. No one had paid much attention to the script on the back of the pictures so it was a whole new avenue of study.

By the time the Sister was ready to be driven back to the convent, I had convinced myself that the album was, indeed, someone else’s. I was now certain that person was a friend of Sister Paraclita, someone named Irvin, a young man she must have been fond of and was encouraging in his painting. I found this theory verified later in another bit of script on the back of yet another drawing:

By the time the Sister was ready to be driven back to the convent, I had convinced myself that the album was, indeed, someone else’s. I was now certain that person was a friend of Sister Paraclita, someone named Irvin, a young man she must have been fond of and was encouraging in his painting. I found this theory verified later in another bit of script on the back of yet another drawing:

Which might have meant that he was a former student (and later soldier friend of her brother), who so admired her that he kept every scrap of art she sent him making an album of them along with the photos she included in her letters over the years.

And the reason all the sketches and paintings in the album were postcard size was in order for her to send them in the wartime mail to her soldier friend. There was also a similar small sketch of a young woman (another former student perhaps?) with the name Lorraine Miller written under it and a picture of a man in uniform, with her brother’s name under it. When I found Sister Paraclita’s painting of the Tepees in her convent archives file -- the one that illustrates the beginning of this story -- I learned her brother was also an Indian Artist. Since Sister Paraclita’s drawing of her brother was in the album it’s very likely that the owner of the album also knew him.

This now explained the photographs of her from a fresh faced nun to a middle aged motherly Sister and the articles about her painting exhibits she must have sent him. Obviously their friendship went a way back in time, even before the war. Perhaps even since grade school. And obviously, if this young man had kept everything she had sent to him with such loving care then no way would he have let it out of his hands willingly.

So, how did the album of Sister Paraclita’s artwork and paintings, Irvin had treasured all his life, end up in a cluttered garage antique shop? And what happened to Irvin?