“Highland” Home of La Vega Clements, Owensboro, Kentucky

Memorabilia in an Old Attic Reveals Forgotten Lore of Notre Dame

In the attic of a stately old Southern mansion owned by The Honorable La Vega Clements remnants of the past lay buried in a huddled heap among other mementos from years gone by.

Over the years, a hole in an attic window had allowed pigeons to roost there and their droppings had rendered much memorabilia storied there useless. After years of being hidden away and forgotten, upon the last death in the family the old mansion was sold and any items in the attic worthy of saving were dispersed among family heirs. How any of these mementos survived – perhaps some were in a battered old trunk – is a little miracle, but some did, only to be stored away once again and forgotten for 88 years. Among them, an old scrapbook filled with worn and ragged newspaper clippings and the tale they had to tell about four adventuresome Notre Dame students, avid football fans, who walked to Chicago to see a Notre Dame football game.Their story would not be here to tell were it not for a chance meeting during my research with, Margaret Moore, the granddaughter of La Vega Clements, whom I had known in high school many years ago. We had lost touch with each other for many years until we met by chance during my research on the Grotto. It was she, who was a realtor at the time, who told me of the “House with Three Flags” at the entrance to Notre Dame and how it had originally been built with a Grotto in the basement. The two of us were invited by the new owner, Notre Dame alumnus Col. Richard Lochner, to see the house he had renovated.

It was during that chance meeting with Margaret, that she learned of my interest in the legends and lore of Notre Dame. Interested, herself, she then told me about finding some old newspaper clippings her father had saved from an old scrapbook that was passed on to her. She said they were about her uncle, Gerald Clements, who like her own father, was also a Notre Dame alumnus. “I really got a kick out of them,” she said, “because I had never heard the story before.” She said it must have caused quite a stir because it was in all the local and the Chicago newspapers. She said her father must have found them in the attic of the “Highland” mansion of his father when it was being sold and kept them as a remembrance of his brother. She had only recently found out about them when they came into her possession when her father passed away. She showed them to me at that time and I made a mental note of them just in case somewhere down the line it might be another good story to add to the legends and lore of the campus.

It was during that chance meeting with Margaret, that she learned of my interest in the legends and lore of Notre Dame. Interested, herself, she then told me about finding some old newspaper clippings her father had saved from an old scrapbook that was passed on to her. She said they were about her uncle, Gerald Clements, who like her own father, was also a Notre Dame alumnus. “I really got a kick out of them,” she said, “because I had never heard the story before.” She said it must have caused quite a stir because it was in all the local and the Chicago newspapers. She said her father must have found them in the attic of the “Highland” mansion of his father when it was being sold and kept them as a remembrance of his brother. She had only recently found out about them when they came into her possession when her father passed away. She showed them to me at that time and I made a mental note of them just in case somewhere down the line it might be another good story to add to the legends and lore of the campus.

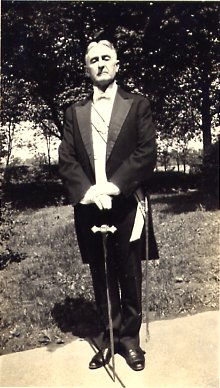

The Honorable La Vega Clements, was a distinguished and gifted lawyer with his own law firm in Owensboro, Kentucky. He was also the Grand Knight of the Knights of Columbus in Owensboro. In 1907 he purchased the “Highland” mansion for his wife, Mamee, and deeded it over to her, as her home always. It was built by the Distiller, Sylvester Monarch. La Vega furnished it lavishly with the finest china and furniture. The library eventually numbered about 500 volumes housed in glass and oak cases.

As the story goes, her grandfather told this story about how he got his name: “My grandfather, Charles O. Clements was with General Zachery Taylor in the Mexican War in 1845. He was present in one of the great battles in which the Mexican General La Vega, was captured. When I was born, he said that I reminded him very much of the old General, and hence he bestowed on me the name of La Vega.”

The above information and the lines that follow from their family genealogy, compiled and written by Elizabeth Clements Harmon, give a wonderful description of La Vega Clements. “It would be an understatement to say La Vega Clements was an out-going man. He was gregarious, people-loving, crowd-pleasing and immensely popular with all who knew him. He never knew a stranger! He was in great demand as a public speaker, as he was witty, urbane, learned, and an entertaining orator. It is difficult to give enough praise and description of his activities and worth -- he was truly ‘larger than life.’ Everything he did was big, grand, and generous.”

La Vega had nine children, three died at an early age. He sent all his children to prep schools and fine institutions of learning. His four sons all went to Notre Dame and two went on to practice with him in his law firm. This story is about one of those sons of Notre Dame who was a member of the adventuresome foursome who walked to Chicago.

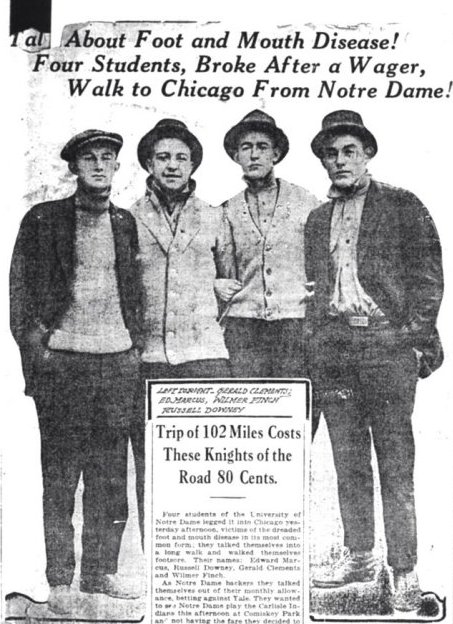

Below is a photograph of them from among a collage of newspaper clippings that were in the forgotten scrapbook stored in the “Highland” mansion attic. Excerpts from numerous articles recount the highlights of their trip which appeared in many different local and Chicago newspapers.

When they sought permission from the Notre Dame authorities the prefect of discipline said: ‘You can go, but I doubt if you will ever make it. I gave some fellows permission to walk to Chicago four years ago, and when they reached Gary one of the fellows took a bath. He got so stiff that he couldn’t get out of the tub.’

Three weeks ago Notre Dame played Yale. As loyal supporters of their team these boys placed their monthly allowances on the game. Yale won. The boys had planned to go to see the Carlisle Indians game with the money they were going to win. It looked impossible to carry out their plans until the idea of walking struck them. The last two weeks have been utilized in walking practice by the boys. They have taken several trips to Niles and back a distance of eight miles. They intend to live without money while on the trip.

‘We are depending upon the great American farmer. If it comes to the worst we can wield an axe like the rest of our fellow hobos. Our sleeping quarters will be anything from a bed at the Salvation Army to a haystack. We expect to have great experiences, but no matter what happens we’ll be in Chi by Saturday and will be in the bleachers when the whistle blows for the kickoff.’

Their first night out they stopped at Laporte and for the munificent sum of two bits road patois for 25 cents they got a flop apiece. One of the boys says they divided the night into watches each one standing guard as a sentry and challenging the bugs who tried to pass the lines. Fourteen bugs, according to our authority, were shot dead and several were severely wounded for not giving the countersign.

Escaping the dangers of this place they again took to the road touching and touching upon New Carlisle, Laporte, Burdick, Chesterton, Gary, East Chicago and Whiting. This pilgrim’s progress was more a case of touching then touching upon. The foot and mouth quarantine shut them out from the farms as they went by and in consequence the trip of 102 miles cost them 80 cents apiece.

The second night out the quartet walked until 10 o’clock, when they came to the house of Albert Marcus in Whiting. He took them in, not in the cosmopolitan, but in the Biblical manner, feeding them profusely on fodder he sent them upon their way, that being Chicagoward, and they arrived at Sox Park at 3:30 yesterday afternoon. They left Notre Dame at 9:00 Wednesday morning.

Chicago, IL, Nov. 14, 1914

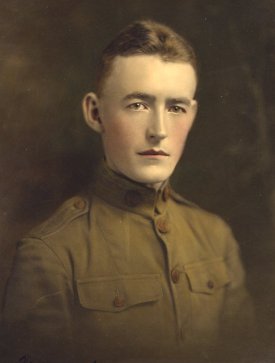

Four students of the University of Notre Dame legged it to Chicago yesterday afternoon victims of the dreaded foot and mouth disease in the most common form. They talked themselves into a long walk and walked themselves footsore. Their names: Edward Marcus, Russell Downey, Wilmer Finch and Gerald Clements, of Owensboro KY, son of The Honorable LaVega Clements.

As Notre Dame backers they talked themselves out of their monthly allowances betting against Yale. They wanted to see Notre Dame play the Carlisle Indians this afternoon at Comiskey Park and not having the fare they decided to walk. They did.

The boys reported themselves as very tired and declared it was a long walk. The distance is 102 miles. They will be guests to-night of Lee Brown, a University of Chicago student, at 5759 Drexel Avenue, and will see the Notre Dame-Carlisle football game to-morrow if they have to walk from Drexel Avenue to the Sox park.

Box seats awaited them when they arrived at Comiskey Park. Notre Dame won 48-6.

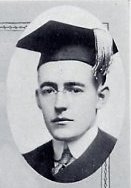

Gerald Clements was a senior in 1914 and his three companions were juniors when they made their famed trek to Chicago. The 1915 Yearbook was very impressive that year. And their trip was not forgotten. In The Dome beside his graduation picture is this description of Gerald Samuel Clements, L.L.B.

A full page in that 1915 Dome contained a reinactment photograph of “The Hikers” and a reappraisal by the famous foursome of:

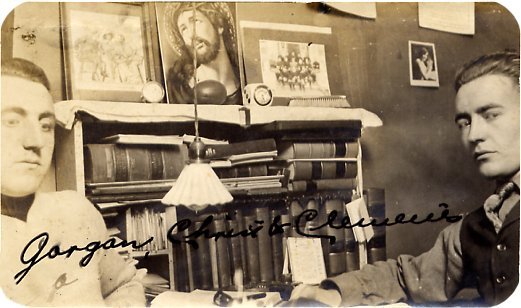

From September, 1913 through June 1915 Gerald resided in Sorin Hall in one of the tower rooms. His roommate was Joseph Gargan. Rose Kennedy, the mother of President John F. Kennedy, was his Aunt. When his mother died he and his sister were raised with the children of Joseph Kennedy. The following year, in 1916, Gerald’s three companions, Edward Marcus, Russell Downey and Wilmer Finch received their degrees and went on to careers in journalism and advertising.

In June of 1915, Gerald Clements graduated with honors in law from Notre Dame University, Valedictorian of his law class. He practiced law in the law firm his father had established which was renamed, Clements & Clements in honor of his eldest child. Gerald had practiced law for 2 years. He was described as a brilliant young lawyer.

In 1917, as soon as World War I was declared, “he exhibited a single minded determination to go to the Army.” Two children had died in infancy and another at four years old. His mother threatened to go to bed “and not get up” if he enlisted. But he had made up his mind, he did enlist in the Army. His mother was devastated but she did not carry out her threat. He was sent to Fort Benjamin Harrison for his basic training, and in September, 1918, he was sent to Camp Sherman at Chillicothe, Ohio where he received general training for overseas duty.

His father wrote to him on September 27, 1918 advising him that “The Spanish flu may hold our shipment of troops back. Don’t see any reports from your camp of any trouble. Hope it doesn’t strike Sherman.” A week later Gerald was stricken with the dreaded 1918 influenza epidemic that was sweeping the civilian and military population of the United States.

Elizabeth Harmon’s geneology describes his last days: A telegram from Camp Sherman informed his mother and father of his serious condition. “They left at once by train . . . Later, they would describe the rows upon rows of stricken soldiers, many dying. Gerald was sick only a few days. At times his fever was so high that he became delirious. In his delirium, he thought he had already gone to France. After their arrival, his mother and father were at his bedside constantly, and they were with him when he died.”

“His last words were: ‘To me, the war is over, and I am going home.’ In one week he would have been twenty-four years old! Ironically, the war really was over only a month later, when the Armistice was signed , November 11, 1918.”

There is yet another irony about the sad untimely death of Gerald Clements. It surfaced in the form of a thought-provoking “Food for Thought” essay he wrote about the war in 1915, before he graduated and returned home to begin his practice as a new lawyer in his father’s law firm.

“The black his mother put on for Gerald’s death and burial, was never laid aside. She wore only black from then, until she died. She made no exceptions for any occasion, including the weddings of her children and grandchildren. She was fifty years old when Gerald died; and she was utterly crushed by grief. For his father it was also a terrible blow. Gerald, his eldest son, had been his daily companion, his partner, and ‘crony’ to talk over everything with.”

When Gerald graduated from Notre Dame in 1915, his father formed the law firm of Clements & Clements. He never changed this designation though Gerald died in 1918. Later his son, Fred, joined the firm, after his graduation from Notre Dame in 1926. They practiced together until La Vega’s death in 1938.

His father’s unforgetable personality continued to guide the family. He died twenty years after Gerald’s death. He had just announced that he would be a candidate for Circuit Judge and had given a speech at the Knights of Columbus Home. After retiring early he was stricken with a heart attack and died before a priest or doctor could get there. He was 70 years old. Elizabeth Harmon describes an interesting story about her grandfather. Many years after his death she said she was visiting her Aunt Lucinda in a nursing home and an old lady came up to her and said about her Aunt Lucinda, “She looks like Mr. Veggie Clements, doesn’t she? When I was young, I used to see him walking down the street, swinging his cane, whistling, saluting ladies by tipping his straw hat and greeting men with a handshake and children with a smile. I thought he was a great man, a real gentleman. (He had been dead 47 years; but she hadn’t forgotten him.)”

Elizabeth writes, “He was ‘one of a kind,’ a legend. He was like a comet streaking across life and then gone. I will never forget him either. He taught me to love reading. He took me on his lap and told me stories, taught me the names of all the Indian tribes. He gave a wonder to all he told. He said, ‘If you read, worlds will be opened up to you.’ I was 9 years old when he died.”

Rev. John W. Cavanaugh, President of the University of Notre Dame paid this same kind of “unforgettable” tribute to Gerald Clements shortly after his death. His words also represent his profound respect for all the young men who gave their lives in service to their country since World War I -- the war to end all wars.

Patriotism, like religion, it would seem, demands for its sacrifice the unblemished lamb. Among all the men who have gone out from Notre Dame holding aloft the banner of freedom, there have been some who have made the supreme sacrifice. Among our thousands of Notre Dame boys in the war, there were, of course, some more select and distinguished than others; but I marvel when I remember that among those who were called in the morning of their promise to give up their lives for human liberty and civilization, there was not one called who was not of the first quality. As I pass the list of names through the fingers of memory, it seems like a rosary of brilliants.

Gerald Clements was one of the noblest, strongest, purest, truest of them all. A face as shining as a child’s; a manner as gentle as a convent girl’s; a breeding as delicate as that of a refined woman; and, yet, an eager quick, challenging and tenacious mind; a vigor of thought, a subtlety of analysis, a balance of judgment this was Gerald Clements.

Let no one wonder that the president of his old University writes so warmly of him. At universities one sees the best men and sees them at their best. It is, of course, the place of study and of labor, but it is also the place of growth and wonder and joy. There young men dream dreams and see visions and plan miraculous achievements for the future--many of which, of course, never mature. It is the home of idealism and in its genial atmosphere the young idealist thrives amazingly.

Gerald Clements was a rare blend of the idealist and the practical man-of-the-world. After he had come into his full power through years and experience, he would have adorned the lecture platform in any university. Equally, he would have been a shining light and a glorious leader in civil or professional life. Always he would be the lovable and faithful home man, the loyal friend, the ideal citizen, the consistent Christian.

He has gone, but he has not died. Men like him never die. As long as there are those who love him and remember him, he is still at work in the world through his spirit, his virtue, his example. God rest his gentle soul.

The name Gerald Clements, is among the names of other sons of Notre Dame who perished during the first World War. Their names are enshrined forever on Memorial Plaques flanking the East Door of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart at the University of Notre Dame. In the foyer of the East Door is also a light fixture made of the World War I helmet of Rev. Charles O'Donnell, a chaplain during World War I and later President of the University.

Statues of St. Joan of Arc and St. Michael the Archangel

flank the portico on the east wing of the Basilica.

I am indebted to Margaret Clements Moore, the wife of Wally Moore, former Notre Dame coach under Ara Parseghian who provided the family photographs and Elizabeth Harmon whose family genealogy supplied the history for this story. Gerald Clements was one of four sons of La Vega Clements of Owensboro, Ky -- Gerald, Menefee, Fred and Spalding. Three graduated from Notre Dame. Two sons, Gerald and Fred, became lawyers and worked for their father. Menefee was one of the first engineers at Bendix. He was head of Engineering Records. Fred, the father of Elizabeth, Margaret, Ann and Marcella left his law practice when La Vega Clements died. He also worked at Bendix. Gerald Clements, the subject of this newspaper story, was the uncle of Elizabeth, Margaret, Ann and Marcella.

I am indebted to Margaret Clements Moore, the wife of Wally Moore, former Notre Dame coach under Ara Parseghian who provided the family photographs and Elizabeth Harmon whose family genealogy supplied the history for this story. Gerald Clements was one of four sons of La Vega Clements of Owensboro, Ky -- Gerald, Menefee, Fred and Spalding. Three graduated from Notre Dame. Two sons, Gerald and Fred, became lawyers and worked for their father. Menefee was one of the first engineers at Bendix. He was head of Engineering Records. Fred, the father of Elizabeth, Margaret, Ann and Marcella left his law practice when La Vega Clements died. He also worked at Bendix. Gerald Clements, the subject of this newspaper story, was the uncle of Elizabeth, Margaret, Ann and Marcella.

Margaret, granddaughter of La Vega Clements found the newspaper clippings about her uncle in an old scrapbook that belonged her father after his death. Margaret and I grew up in the same neighborhood and were school chums. When Margaret came over to view the finished Web pages before they went online she brought this picture of herself, from bygone days and I shared one I had with her. I had never seen her picture at that age and she hadn’t seen mine.

Margaret Clements (Clem to her school chums) went to parochial schools and I went to public schools. Though we lived a street away from each other we did not meet until she switched to the newly built John Adams High School for her last two years of high school (my father was the masonry superintendent during its construction.) Shortly after graduation, Margaret married and moved away. It was twenty years before we saw each other again.

One day I received a flyer in the mail from Robertsons, one of our local department stores. In it, was a picture of a pretty girl modeling a dress the store was advertising. I was sure it was Clem, my old school chum with her model good looks. I wondered if she might have returned to her hometown. Would her parents still be living in the same house? Nothing ventured, nothing gained, I called to ask about her.

Her widowed father, who died shortly thereafter, informed me that she was back and living in South Bend. A little detective work, and I found her. I sent the picture to her and then followed up with a phone call. She laughed at the way I found her, and said though she appreciated the compliment she was not the model in the photograph. We were soon happily picking up where we left off meeting occasionally for lunch and exchanging letters now and then. Then she moved away again.

Margaret has been a career woman all her life with five children to raise. While I was a stay-at-home mom from the time our son, our only child, was born. The years flew by -- as they can when raising children -- and we lost track of each other again.

Then one day in the mid-nineties, another twenty years later, our paths crossed again when we met by chance in the University Park Mall. I was doing my research at Notre Dame at the time and she was then working as a realtor. When she learned of my Grotto research she remembered a house with a Grotto in the basement as one of her listings. All of which led to my Notre Dame Legends and Lore story called, “Dooley and the House with Three Flags.”

The owner invited us both to see his newly rennovated home and our lives merged again. Not too long after that Margaret found her father’s scrapbook and told me about it. “A Walk to Chicago” became another great story to add to the Legends and Lore stories.

And so, as fate (or Providence) would have it, Margaret and I have now come, full circle, back to those carefree high school days when we were comfortable and at ease in each other’s company.

In her retirement, Margaret and Wally Moore’s four bedroom empty nest has become a Bed & Breakfast during the Notre Dame football season. Which is a treat for them -- and their Notre Dame guests -- since Wally Moore was a former football coach for Ara Parseghian at Notre Dame.

When Margaret followed her intuition and brought along her high school picture, I followed mine, and added this postscript as more evidence that one should never underestimate those meaningfully related events and positive energies that radiate from obeying one’s intuitive impulses.

Dorothy V. Corson

April 5, 2003