A Brief Biography of

Lewis Mumford (1895-1990)

by Eugene Halton

"Certainly it is not in extensive cosmonautic explorations of

outer space, but by more intensive cultivation of the historic inner spaces of

the human mind, that we shall recover the human heritage. In a sense, all my

major books, starting with Technics and Civilization, the first volume

in The Renewal of Life series, have been attempts to understand the

repeated miscarriages of mind that have limited the highest achievements of

every historic civilization. My maturest interpretation

of the archaeological and historic evidence will be found in three successive

books: The City in History, 1960, Technics and Human Development,

1967, and The Pentagon of Power, 1970."

In

Mumford, Lewis. 1972. "Two Views of Technology and Man." Technology, Power, and Social Change, Charles Thrall and Jerold

Starr, eds. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, pp. 1-16.

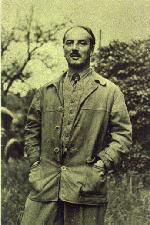

Internationally

renowned for his writings on cities, architecture, technology, literature, and

modern life, Lewis Mumford was called "the last of the great

humanists" by Malcolm Cowley. His contributions to literary criticism,

architectural criticism, American studies, the history

of cities, civilization, and technology, as well as to regional planning,

environmentalism, and public life in America, mark him as one of the most

original voices of the twentieth-century.

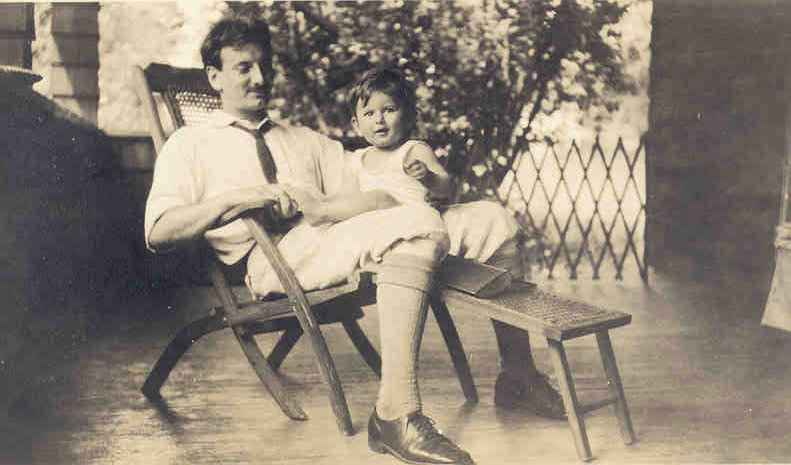

Born in Flushing on October 19, 1895, Mumford lived much of his life in New

York, settling in Dutchess County in 1936 with his

wife Sophia, in Amenia, where he died over a

half-century later, on January 26, 1990. His first book, The Story of

Utopias, was published in 1922, and his last book, his autobiography, Sketches from Life, was published sixty years

later in 1982.

Mumford preferred to call himself a writer, not a scholar, architectural

critic, historian or philosopher. His writing ranged freely and brought him

into contact with a wide variety of people, including writers, artists, city

planners, architects, philosophers, historians, and archaeologists. Throughout

his life, Mumford sketched and painted his surroundings, visualizing his

impressions of people and places in image, as his ever-present notepad

visualized them in words.

Given the range of Mumford's scholarly work, it is all the more interesting

that he did not have a college degree, having had to leave City College of New

York after a diagnosis of tuberculosis. But if whaling was Herman Melville's

Harvard and Yale, Mannahatta, as Mumford put it, was

my university, my true alma mater. From childhood on, Mumford walked, sketched,

and observed New York City, and its effects can be felt throughout his

writings.

He was architectural critic for The New Yorker magazine for over thirty years,

and his 1961 book, The City in History, received the National Book

Award. In 1923 Mumford was a cofounder with Clarence Stein, Benton MacKaye,

Henry Wright and others, of the Regional Planning Association of America, which

advocated limited-scale development and the region as significant for city planning.

By 1938 he was an ardent advocate for early American entry into what

was emerging as World War Two, a war which claimed the life of his son

Geddes in 1944, and was an early critic of nuclear weapons in 1946 and of U.S.

involvement in Vietnam in 1965. In 1964 he was awarded the Presidential Medal

of Freedom.

Lewis Mumford's work underwent a continuous series of transformations as he

broadened and deepened his scope. From his American studies books in the 1920s,

such as The Golden Day (1926) and Herman Melville (1929), which

contributed to the rediscovery of the literary transcendentalists of the 1850s

and The Brown Decades (1931) which placed the architectural achievements

of Henry Hobson Richardson, Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright before the

public, through the four-volume "Renewal of Life" series published

between 1934 and 1951, which outlined the place of technics, cities, and

world-views in the development of Western Civilization, to his late studies of

the emergence of civilizations and the place of communication practices in

human development, he boldly denied the utilitarian view while evolving his own

vision of organic humanism.

Mumford's works share a common concern with the ways that modern life as a

whole, although providing possibilities for broader expression and development,

simultaneously subverts those possibilities and actually ends up tending toward

a diminution of purpose. He shows in lucid detail how the modern ethos released

a Pandora's box of mechanical marvels which eventually threatened to absorb all

human purposes into

The Myth of the Machine, the title he used for his

two-volume late work.

See, for example, Lewis

Mumford's critique of the World Trade Center from

1970, when it was just being built.

Despite what he saw as a likelihood of catastrophic dehumanization on the

horizon, he argued for the hope that the organic depths of human nature, of the

fibrous structure of history, might provide the basis for a transformation of

megatechnic civilization.

Mumford argued passionately for a restoration of organic human purpose in the

larger scheme of things, a task requiring a human personality capable of

"primacy over its biological needs and technological pressures, and able

to draw freely on the compost from many previous cultures."

As he

wrote in his 1946 book, Values for Survival:

"If we are to create balanced human beings, capable of entering into

world-wide co-operation with all other men of good will--and that is the

supreme task of our generation, and the foundation of all its other potential

achievements--we must give as much weight to the arousal of the emotions and to

the expression of moral and esthetic values as we now give to science, to

invention, to practical organization. One without the other is impotent. And

values do not come ready-made: they are achieved by a resolute attempt to

square the facts of one's own experience with the historic patterns formed in

the past by those who devoted their whole lives to achieving and expressing

values. If we are to express the love in our own hearts, we must also

understand what love meant to Socrates and Saint Francis, to Dante and

Shakespeare, to Emily Dickinson and Christina Rossetti, to the explorer

Shackleton and to the intrepid physicians who deliberately exposed themselves

to yellow fever. These historic manifestations of love are not recorded in the

day's newspaper or the current radio program: they are hidden to people who

possess only fashionable minds. Virtue is not a chemical product, as Taine once

described it: it is a historic product, like language and literature; and this

means that if we cease to care about it, cease to cultivate it, cease to

transmit its funded values, a large part of it will become meaningless, like a

dead language to which we have lost the key. That, I submit, is what has

happened in our own lifetime."

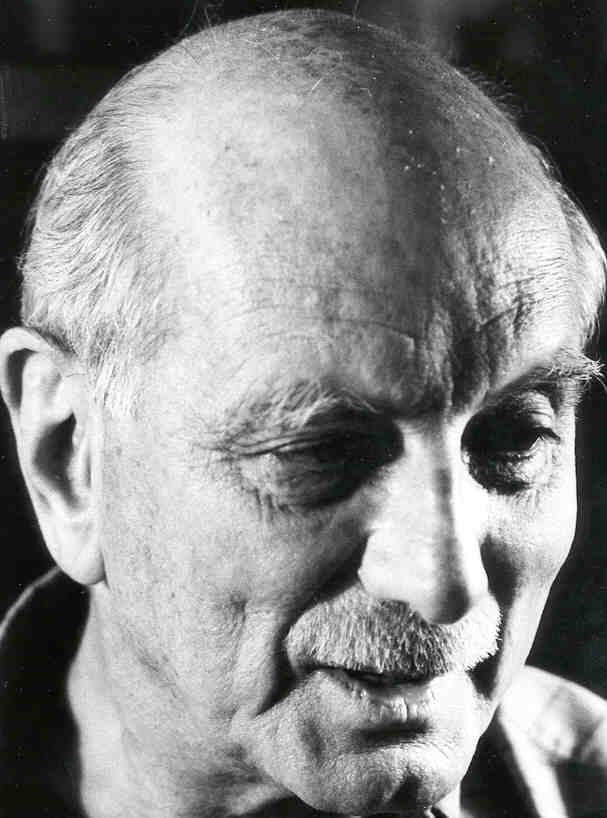

Mumford's 1982 autobiography was followed by a biography by Donald Miller in

1989, Lewis Mumford: A Life, New York: Weidenfeld

& Nicolson, 1989.

Mumford's

papers are stored in Philadelphia at the Van Pelt Library of The University of

Pennsylvania, and his library and watercolors and drawings are stored at the

library of Monmouth

University, West Long Branch, New Jersey.

************

Videos online:

"Lewis Mumford on the City." Entire series is available on National Filmboard of Canada website:

https://www.nfb.ca/search#?queryString=mumford&index=0&language=en

Lewis Mumford from BBC

documentary Towards Tomorrow: A Utopia. 1968 copy [2:21]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gARS4F90wmw

The City (1939) w/ commentary

by Mumford. Music by Aaron Copeland

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7nuvcpnysjU

See also my discussions of Mumford:

Eugene

Halton, Chapter 12, The Last

Days of Lewis Mumford, from The

Great Brain Suck: And Other American Epiphanies, University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Eugene

Halton, From the Axial Age to the Moral Revolution, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

The

book contains numerous discussions of Mumford's writings related to Karl Jaspers' theory of

axial age, the period centered roughly around 500-600 BCE, and to John Stuart-Glennie's prior original idea that Stuart-Glennie

termed in 1873 "the

moral revolution," 75 years before Jaspers. Chapter 5 is titled "Jaspers

and Mumford."

Eugene

Halton, Chapter 4, Lewis Mumford's Organic Worldview,

from Bereft of Reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

************

Books by Lewis

Mumford (Listed Chronologically)

The Story of Utopias. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1922.

Sticks and Stones: A Study of

American Architecture and Civilization. New York: Boni and Liveright,

1924.

The Golden Day: A Study in

American Experience and Culture. New York: Harcourt Brace

and Co., 1926.

Herman Melville. New York: The Literary

Guild of America, 1929.

The Brown Decades: A Study of

the Arts in America,1865-1895. New York: Harcourt Brace

and Co., 1931.

Technics and Civilization. New York: Harcourt Brace

and Co., 1934.

The Culture of Cities. New York: Harcourt Brace

and Co., 1938.

Men Must Act. New York: Harcourt Brace

and Co., 1939

Faith for Living. New York: Harcourt Brace

and Co., 1940.

The South in Architecture. New York: Harcourt Brace

and Co., 1941.

The Condition of Man. New York: Harcourt Brace

and Co., 1944.

City Development: Studies in

Disintegration and Renewal. New

York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1945

Values for Survival: Essays,

Addresses, and Letters on Politics and Education. New York: Harcourt Brace

and Co., 1946.

Green Memories: The Story of

Geddes. New

York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1947.

The Conduct of Life. New York: Harcourt Brace

and Co., 1951.

Art and Technics. New York: Columbia

University Press, 1952

In the Name of Sanity. New York: Harcourt Brace

and Co., 1954.

From the Ground Up. New York: Harcourt Brace

World, 1956.

The Transformations of Man. New York: Harper and Row,

1956.

The City in History: Its

Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. New York: Harcourt Brace and World, 1961.

The Highway and the City. New York: Harcourt Brace

and World, 1963.

The Urban Prospect. New York: Harcourt Brace

Jovanovich, 1968.

The Myth of the Machine:

Vol.

I, Technics and Human Development. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1967; Vol. II, The

Pentagon of Power. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich,1970.

Interpretations and Forecasts

1922-1972.

New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

Findings and Keepings: Analects for an

Autobiography.

New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975.

My Works and Days: A Personal

Chronicle.

New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979.

Sketches from Life: The

Autobiography of Lewis Mumford. New York: Dial Press, 1982.

The Lewis Mumford Reader. Donald L. Miller, ed. New York: Pantheon Books, 1986.

************

Eugene Halton