LEARNING MORE ABOUT THE MUSIC WE SING

|

Lesson 6, for April 8

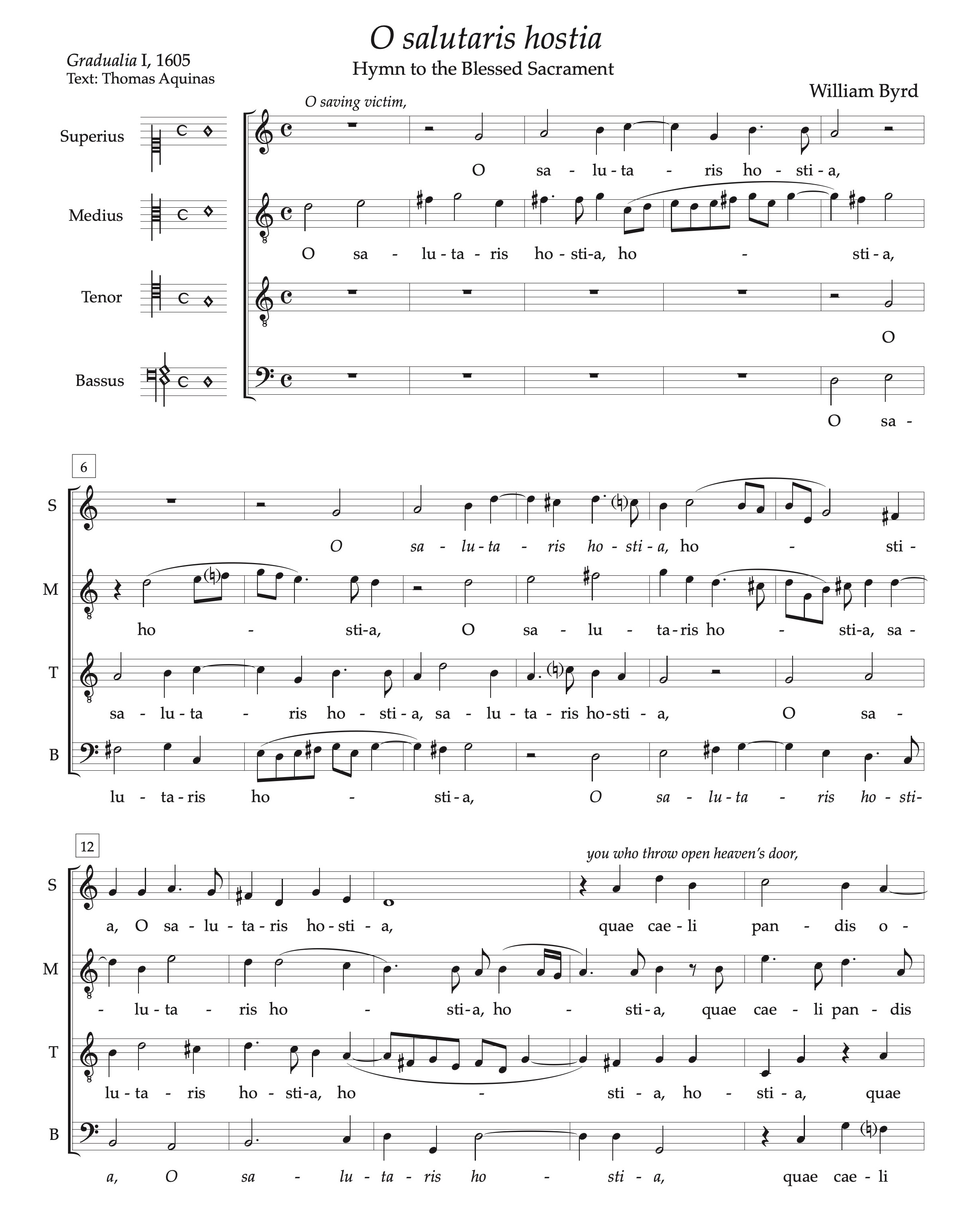

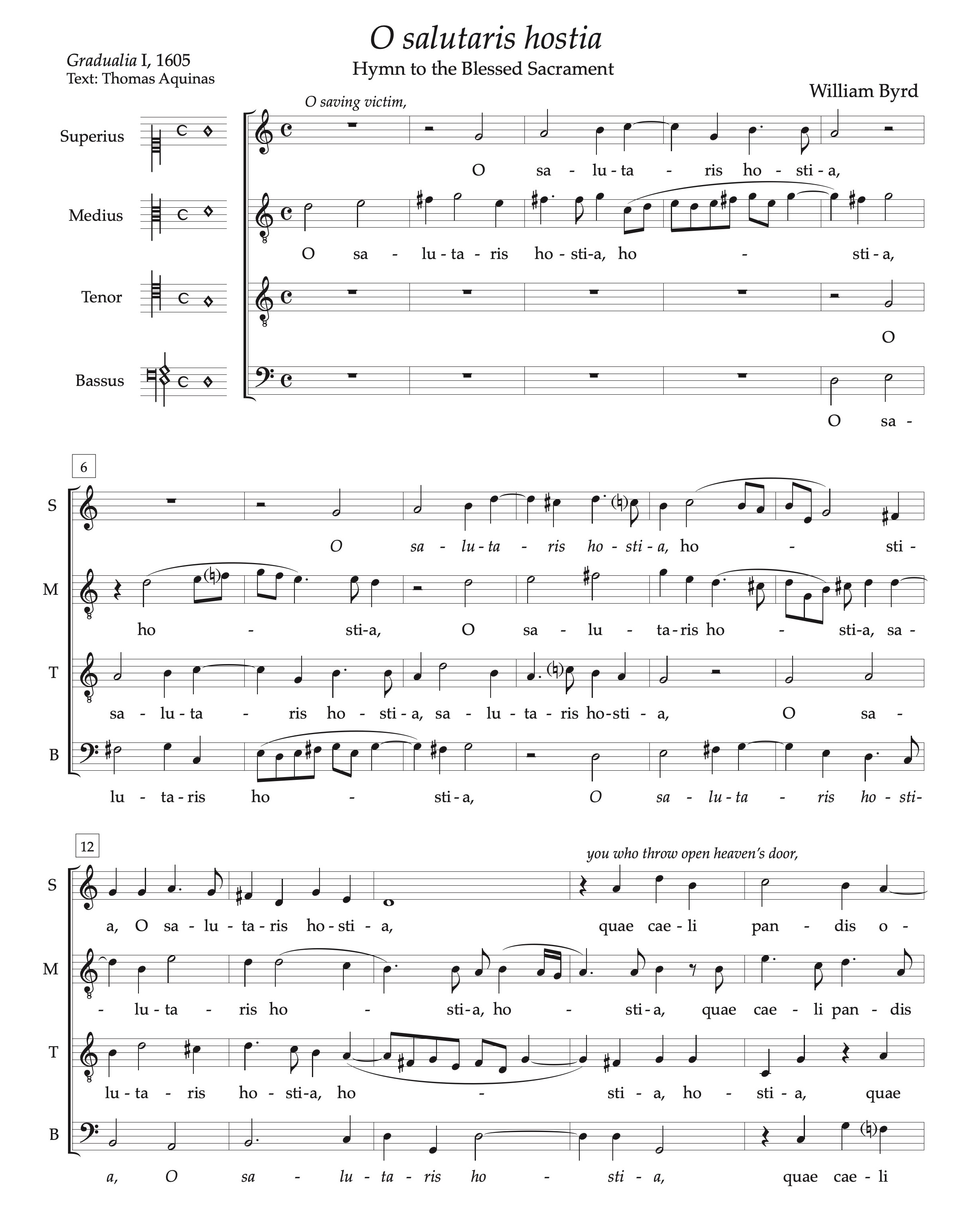

If you look carefully at Byrd’s O salutaris hostia (below), you can see that the first motif for the Medius is repeated, sort of, at mm. 8-10. That is, the motif begins the same the second time, but then goes in a different direction. The same thing happens in the Superius, except here only the first three notes are repeated exactly. If you look at the first and second Tenor motifs, you can see that they follow what happens in the Superius. But note that the Tenor doesn’t follow the Bassus at the same place that the Superius follows the Medius: the Tenor comes in just one half-note after the Bassus, whereas the Superius follows the Medius by three half-notes. This is Byrd’s standard technique: there is just enough similarity in motifs and counterpoint for the ear to hear them as variants of one another, but in actuality they are not really the same. It is a very sophisticated form of imitation! (The more symmetrical form of imitation can be found in most pieces by Josquin Desprez and Palestrina.) Why does Byrd like the asymmetrical technique so much, and use it so often? Because he likes to create subtle cross-rhythms of inexact phrases that still function as correct counterpoint. You could liken it to the difference between metrical poetry and prose. Byrd writes an especially flowing and brilliant form of prose.

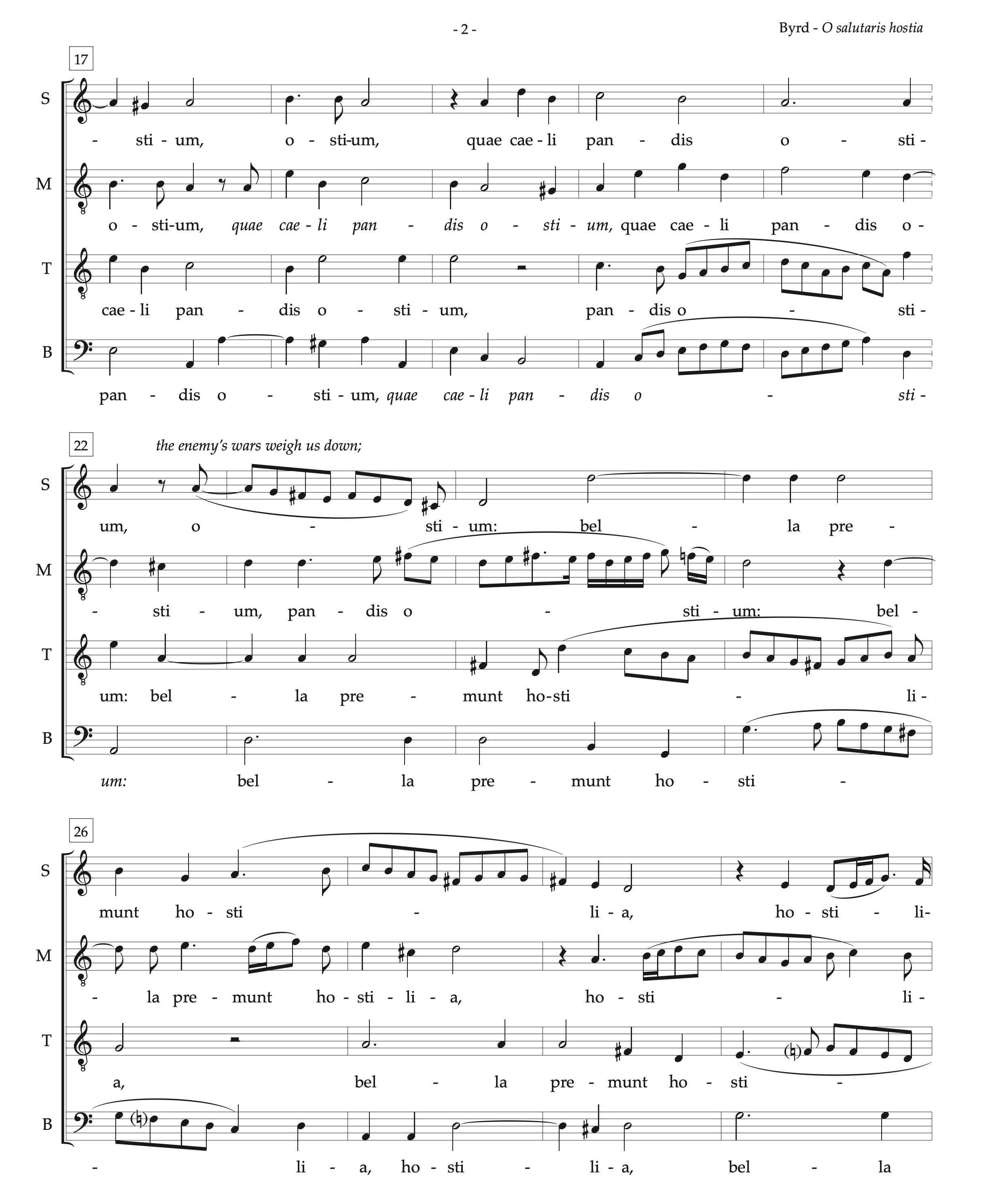

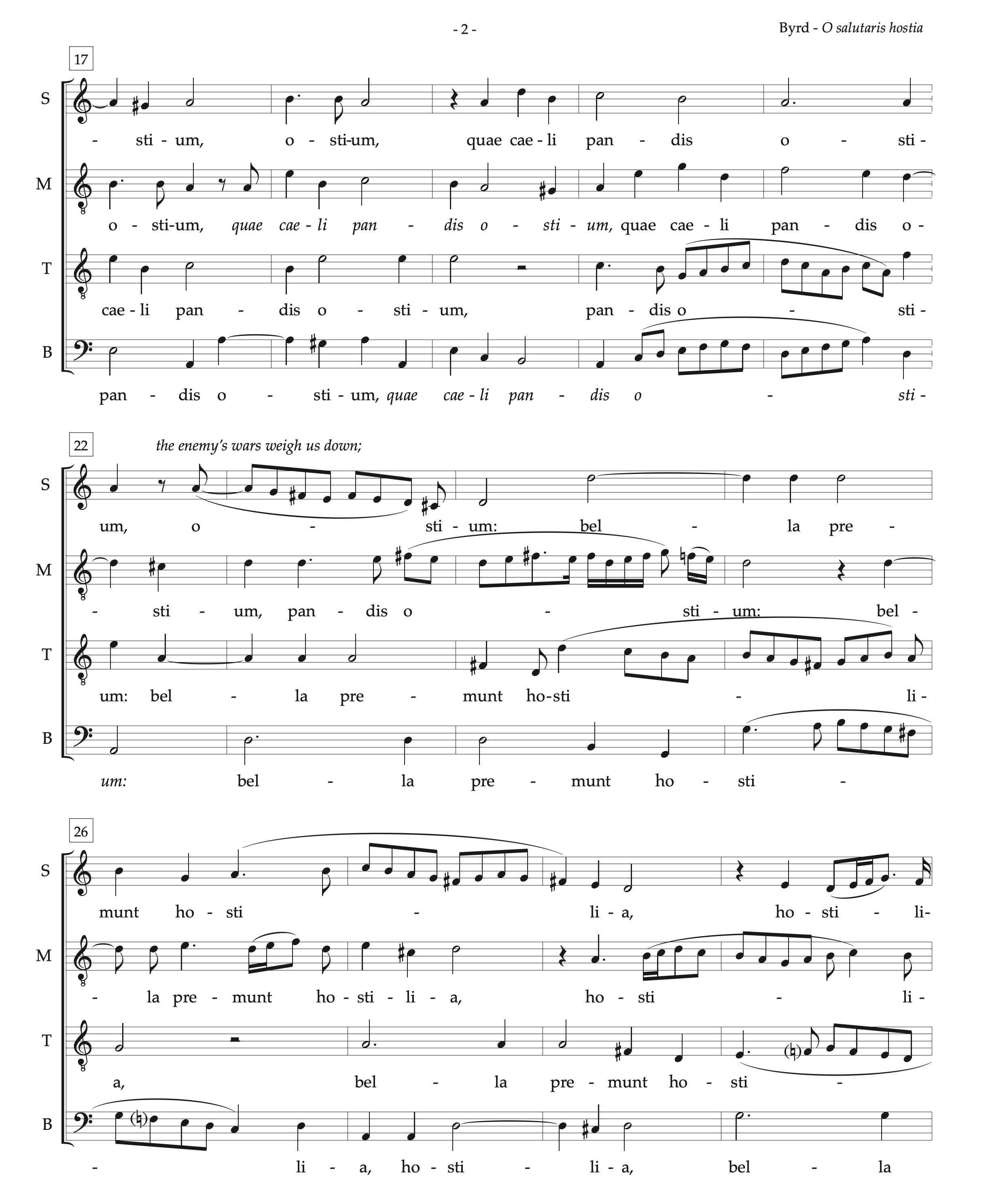

At m. 9 you can see that a C-sharp in the top voice is still sounding when the Tenor sings a C-natural. The clash of C-sharp against C-natural is known as a cross relation, in fact an especially intense form, where the C-sharp and C-natural happen simultaneously. (In the less intense form of cross relation, the clashing notes follow one another closely but do not sound at the same time.) The clashing notes of cross relations typically are sharp and natural, or flat and natural, forms of the same pitch. How many simultaneous cross relations can you find in this piece? How many cross relations that are not simultaneous? How many cross-relation events that are not true cross relations because the clashing notes don’t immediately follow one another?

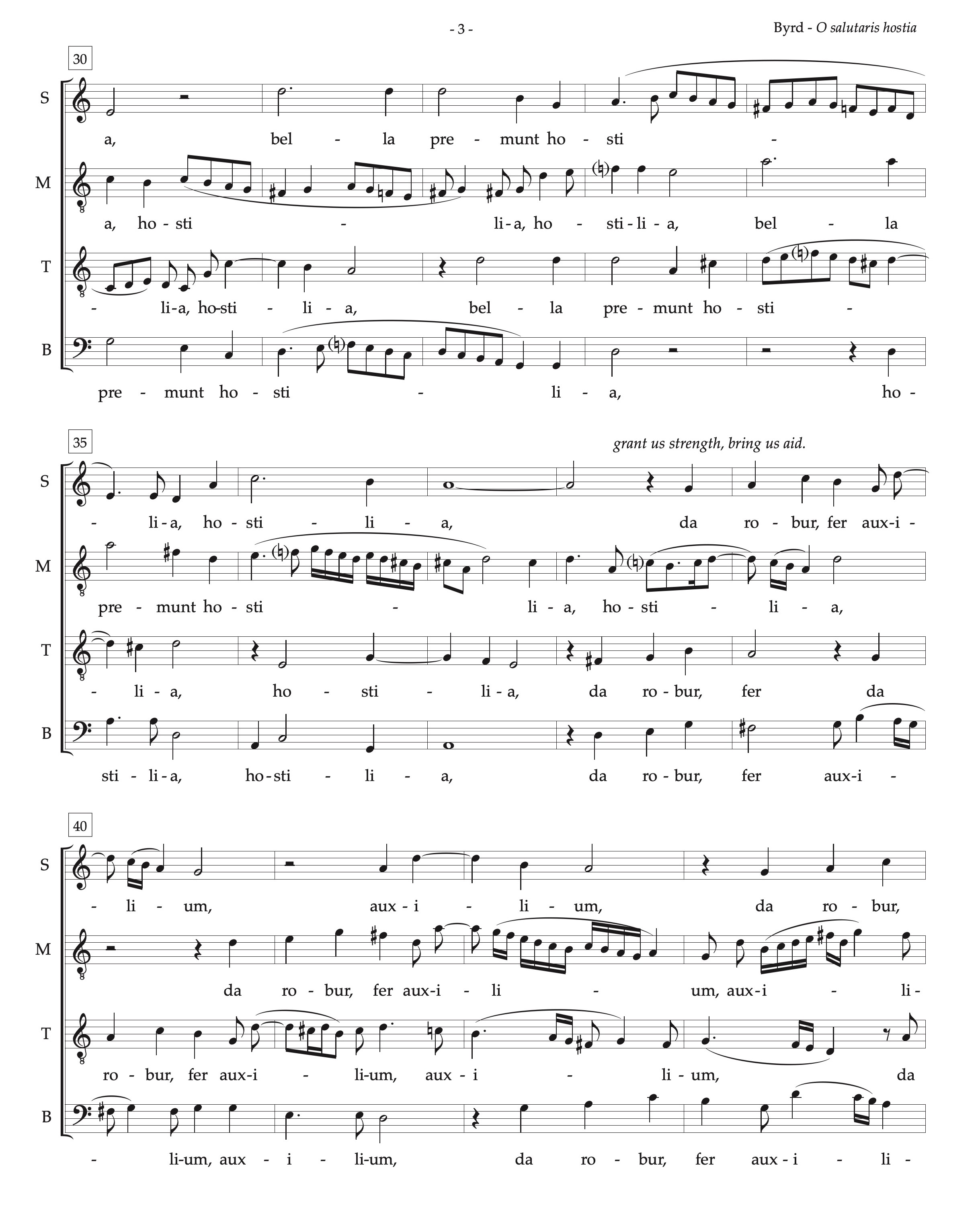

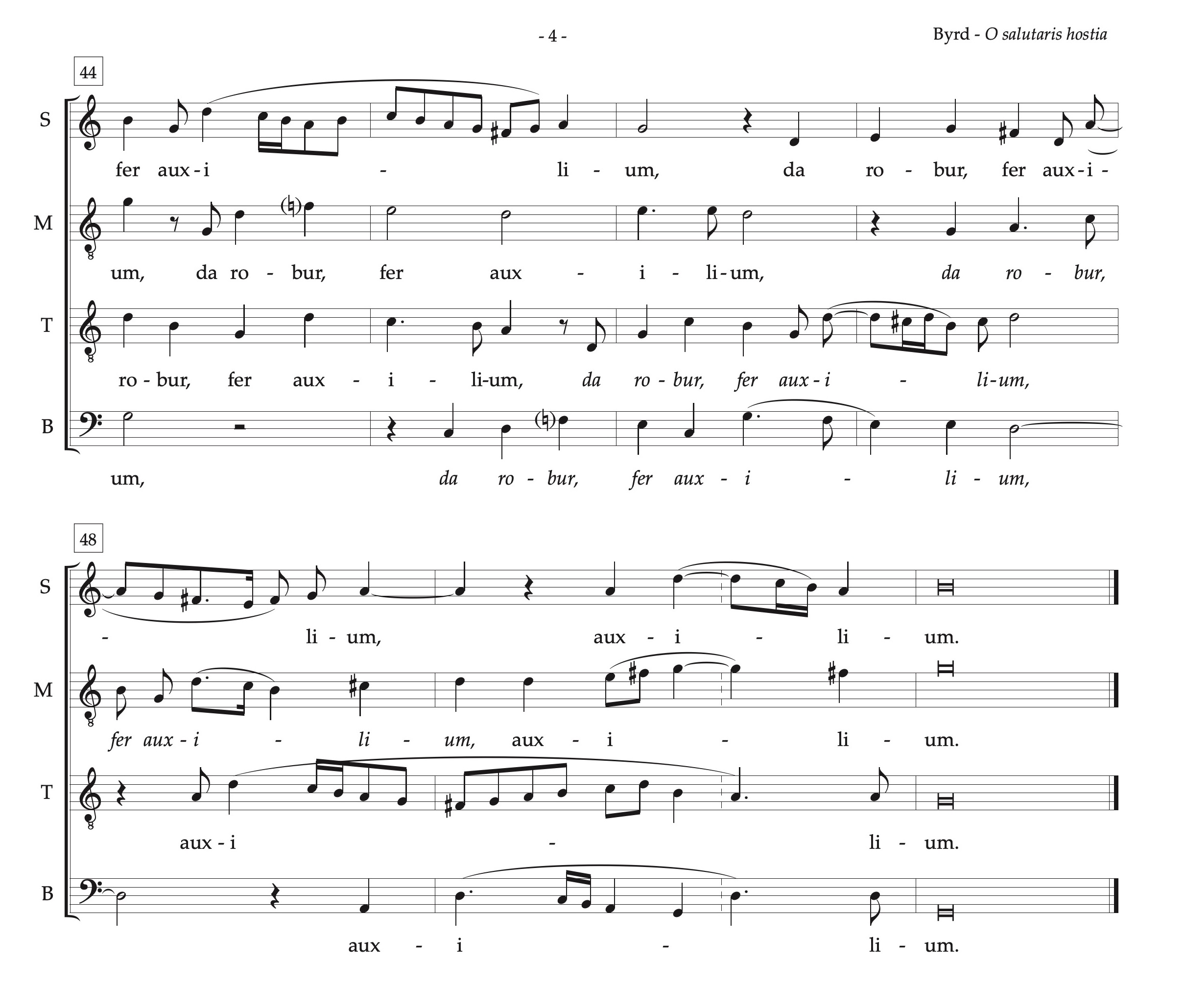

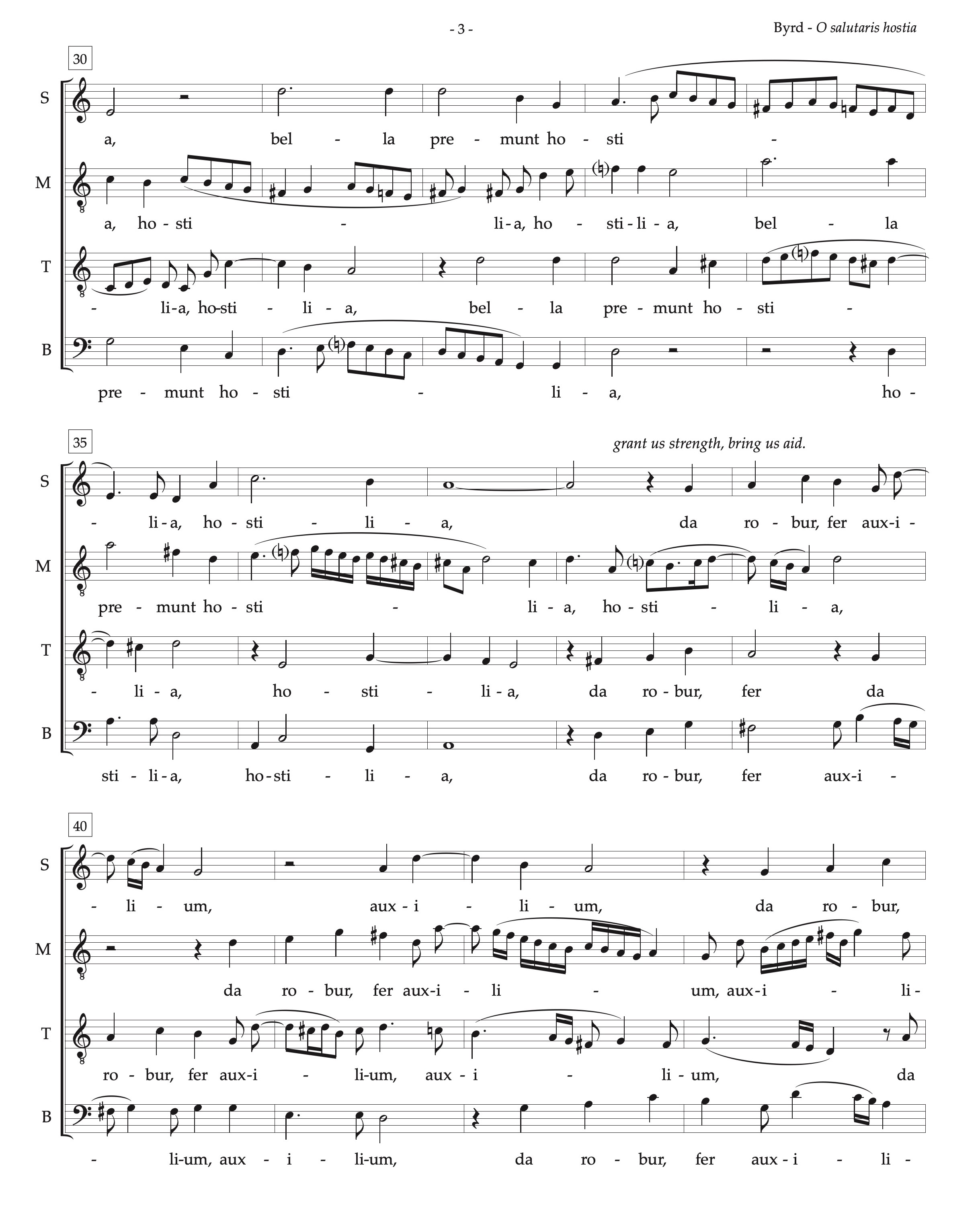

Let’s look now at the phrase “bella premunt hostia,” beginning in the Tenor at m. 22. Note that it begins in the middle of a short measure and is followed immediately by (almost) the same musical phrase a fifth lower in the Bassus. One and a half measures later it appears up two octaves in the Superius, followed two and a half measures later in the Tenor. Two measures later it is in the Bassus again, followed two measures later in the Superius, followed one measure later in the Tenor and two measures later still in the Medius. This is Byrd’s asymmetry at its most sophisticated. What happens to our listening during this passage? We hear and recognize the musical motif that goes with the “bella premunt hostia” words, but we can’t predict when and where the next statement of the motif will occur. But since Byrd is such a master of harmony, we always feel, upon hearing the next statement of the motif, that it has been logically prepared.

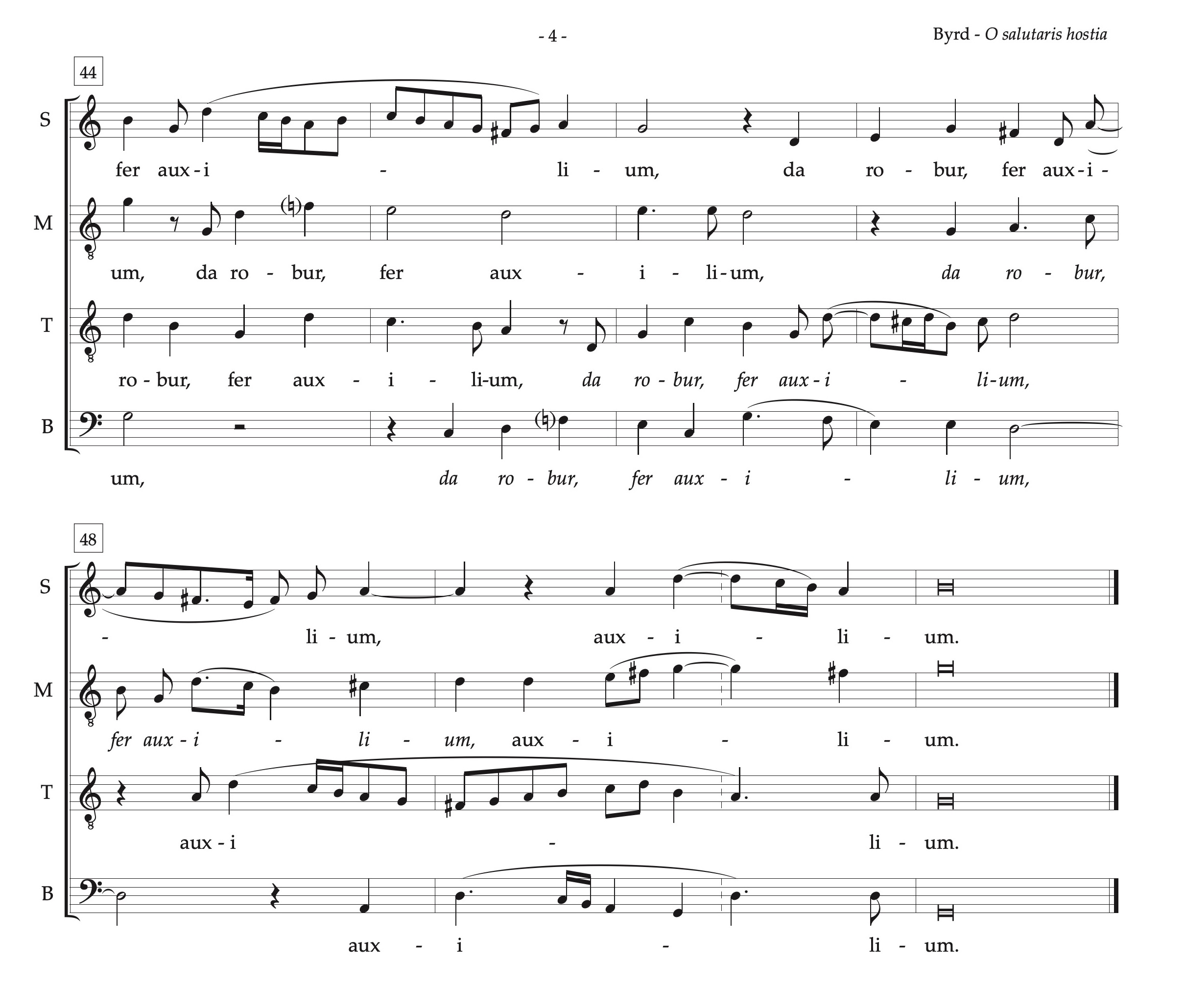

Let’s look at those sixteenth-note runs in the Medius (mm. 24, 36, 42, and 43). These are not easy to sing! In fact, they are not really vocal at all. Rather, they produce ornamental counterpoint borrowed from instrumental usage, where such musical figures are idiomatic. Runs like these are common for the lute in music for mixed ensembles of instruments by Byrd and his contemporaries. Here Byrd is counting on his singers to be flexible and agile, which only skilled singers can be. The demands of the score tell us something about the level of singers Byrd expected to sing his music.

Finally, what about that introductory measure with old clefs and old notation? The purpose of that measure is to show which clefs Byrd used (some combinations of clefs indicated transposition), which note values (you can’t necessarily tell from the modern edition, because editors often halve or quarter the durations of the notes, as happens in this edition, where the note values are halved), and what the original pitch level was, in case the modern edition transposes the music, as often happens to make the music fit a particular choir better. For the modern performer who doesn’t have access to the original print, the introductory measure shows exactly how the modern edition has changed or not changed important features of the original.

End of Lesson 6. Click here to continue to Lesson 7, for April 13. Click here to return to the Lesson List.

|

|