Project 06: Simple File System

Overview

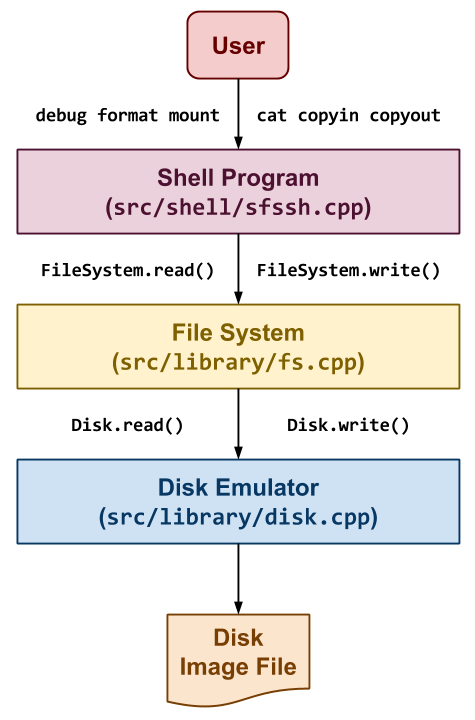

The last project is to build a simplified version of the Unix File System called SimpleFS as shown to the right. In this application, we have three components:

-

Shell: The first component is a simple shell application that allows the user to perform operations on the SimpleFS such as printing debugging information about the file system, formatting a new file system, mounting a file system, creating files, and copying data in or out of the file system. To do this, it will translate these user commands into file system operations such as

FileSystem.debug,FileSystem.format,FileSystem.debug,FileSystem.create,FileSystem.readandFileSystem.write. -

File System: The second component takes the operations specified by the user through the shell and performs them on the SimpleFS disk image. This component is charged with organizing the on-disk data structures and performing all the bookkeeping necessary to allow for persistent storage of data. To store the data, it will need to interact with the disk emulator via methods such as

Disk.readandDisk.write, which allow the file system read and write to the disk image in4096byte blocks. -

Disk Emulator: The third component emulates a disk by dividing a normal file (called a disk image) into

4096 byteblocks and only allows the File System to read and write in terms of blocks. This emulator will persistently store the data to the disk image using the normal open, read, and write system calls.

The shell and disk emulator components are provided to you. You only have to complete the file system portion of the application for this project.

Simple File System Design

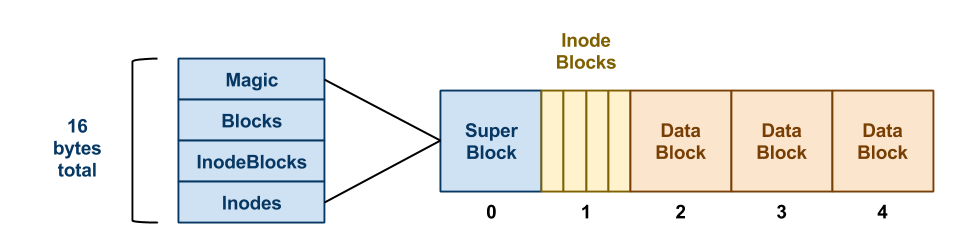

To implement the file system component, you will first need to

understand the SimpleFS disk layout. As noted previously, this project

assumes that disk blocks are the common size of 4KB. The first block of

the disk is the superblock that describes the layout of the rest of the

filesystem. A certain number of blocks following the superblock contain

inode data structures. Typically, ten percent of the total number of

disk blocks are used as inode blocks. The remaining blocks in the

filesystem are used as plain data blocks, and occasionally as

indirect pointer blocks as shown in the example below:

In this example, we have a SimpleFS disk image that begins with a superblock. This superblock consists of four fields:

-

Magic: The first field is always the

MAGIC_NUMBERor0xf0f03410. The format routine places this number into the very first bytes of the superblock as a sort of filesystem "signature". When the filesystem is mounted, the OS looks for this magic number. If it is correct, then the disk is assumed to contain a valid filesystem. If some other number is present, then the mount fails, perhaps because the disk is not formatted or contains some other kind of data. -

Blocks: The second field is the total number of blocks, which should be the same as the number of blocks on the disk.

-

InodeBlocks: The third field is the number of blocks set aside for storing inodes. The format routine is responsible for choosing this value, which should always be

10%of the Blocks, rounding up. -

Inodes: The fourth field is the total number of inodes in those inode blocks.

Note that the superblock data structure is quite small: only 16

bytes. The remainder of disk block zero is left unusued.

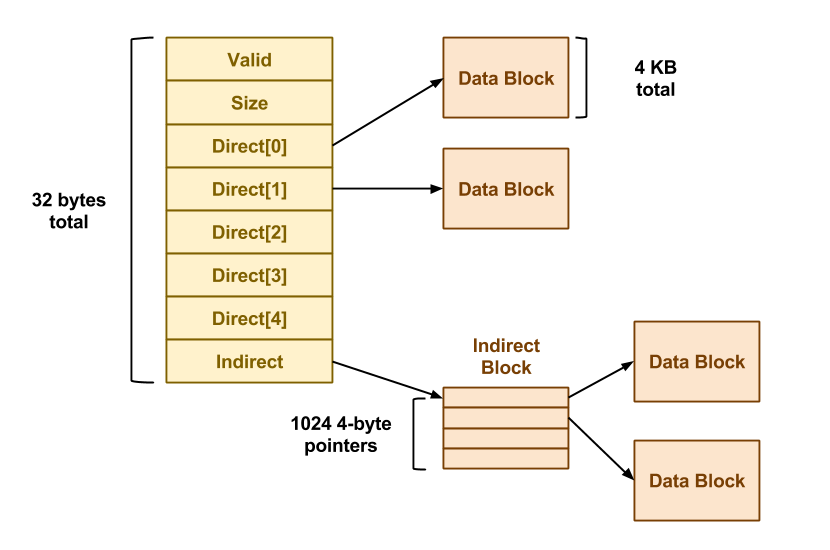

Each inode in SimpleFS looks like the file:

Each field of the inode is a 4-byte (32-bit) integer. The Valid

field is 1 if the inode is valid (i.e. has been created) and is 0

otherwise. The Size field contains the logical size of the inode

data in bytes. There are 5 direct pointers to data blocks, and one

pointer to an indirect data block. In this context, "pointer" simply

means the number of a block where data may be found. A value of 0 may be

used to indicate a null block pointer. Each inode occupies 32 bytes, so

there are 128 inodes in each 4KB inode block.

Note that an indirect data block is just a big array of pointers to

further data blocks. Each pointer is a 4-byte int, and each block is

4KB, so there are 1024 pointers per block. The data blocks are simply

4KB of raw data.

One thing missing in SimpleFS is the free block bitmap. As discussed in class, a real filesystem would keep a free block bitmap on disk, recording one bit for each block that was available or in use. This bitmap would be consulted and updated every time the filesystem needed to add or remove a data block from an inode.

Because SimpleFS does not store this on-disk, you are required to keep a free block bitmap in memory. That is, there must be an array of integers, one for each block of the disk, noting whether the block is in use or available. When it is necessary to allocate a new block for a file, the system must scan through the array to locate an available block. When a block is freed, it must be likewise marked in the bitmap.

Suppose that the user makes some changes to a SimpleFS filesystem, and then reboots the system (ie. restarts the shell). Without a free block bitmap, SimpleFS cannot tell which blocks are in use and which are free. Fortunately, this information can be recovered by scanning the disk. Each time that an SimpleFS filesystem is mounted, the system must build a new free block bitmap from scratch by scanning through all of the inodes and recording which blocks are in use. (This is much like performing an fsck every time the system boots.)

SimpleFS looks much like the Unix file system. Each "file" is identified by an integer called an inumber. The inumber is simply an index into the array of inode structures that starts in block one. When a file is created, SimpleFS chooses the first available inumber and returns it to the user. All further references to that file are made using the inumber. Using SimpleFS as a foundation, you could easily add another layer of software that implements file and directory names. However, that will not be part of this assignment.

More details about this project and your deliverables are described below.

File Systems

While it may seem that file systems are a solved problem with venerable examples such as Ext4, XFS, and NTFS, the growth in big data and the emergence of SSDs as the primary storage medium has once again made file systems a hot topic. Today, we have next-generation file systems in the form of ZFS, Btrfs, and AppleFS, which build upon the foundation set by previous file systems. In this assignment, you will explore the core principles about file systems and how they work.

Note: This assignment is based heavily on Project 6: File Systems by Doug Thain.

Deliverables

Working in groups of one or two people (three is discouraged,

but allowed), you are to create a library that implements the

FileSystem class described above and demonstrate it to a member of the

instructional staff by Wednesday, December 13, 2017.

For this project, you must use C++ (not C) as the implementation language. Any test scripts or auxillary tools can be written in any reasonable scripting language.

Timeline

Here is a timeline of events related to this project:

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| Tuesday, November 28 | Project description and repository are available. |

| Wednesday, December 13 | Demonstrations of file system completed. |

Repository

To start this project, one group member must fork the Project 06 repository on GitLab:

https://gitlab.com/nd-cse-30341-fa17/cse-30341-fa17-project06

Once this repository has been forked, follow the instructions from Reading 00 to:

-

Make the repository private.

-

Configure access to the repository.

Make sure you add all the members of the team in addition to the instructional staff.

Source Code

As you can see, the base Project 06 repository contains a README.md

file and the following folder hierarchy:

project06

\_ Makefile # This is the project Makefile

\_ bin # This contains the application executables and scripts

\_ include # This contains the SimpleFS library header files

\_ sfs

\_ disk.h # This contains the Disk Emulator header file

\_ fs.h # This contains the File System header file

\_ src

\_ library

\_ disk.cpp # This contains the Disk Emulator implementation code

\_ fs.cpp # This contains the File System implementation code

\_ shell

\_ sfssh.cpp # This contains the Shell implementation code

\_ tests # This contains the test scripts

You must maintain this folder structure for your project and place files in their appropriate place.

Of the provided files, you are only required to modify the

include/sfs/fs.h and src/library/fs.cpp files as described below.

To build the project, you can simply use make:

$ make g++ -g -gdwarf-2 -std=gnu++11 -Wall -Iinclude -fPIC -c -o src/library/disk.o src/library/disk.cpp g++ -g -gdwarf-2 -std=gnu++11 -Wall -Iinclude -fPIC -c -o src/library/fs.o src/library/fs.cpp ar rcs lib/libsfs.a src/library/disk.o src/library/fs.o g++ -g -gdwarf-2 -std=gnu++11 -Wall -Iinclude -fPIC -c -o src/shell/sfssh.o src/shell/sfssh.cpp g++ -Llib -o bin/sfssh src/shell/sfssh.o -lsfs

K.I.S.S.

While the exact organization of the project code is up to you, keep in mind that you will be graded in part on coding style, cleaniness, and organization. This means your code should be consistently formatted, not contain any dead code, have reasonable comments, and appropriate naming among other things:

-

Break long functions into smaller functions.

-

Make sure each function does one thing and does it well.

-

Abstract, but don't over do it.

Please refer to these Coding Style slides for some tips and guidelines on coding style expectations.

Disk Emulator

As noted above, we provide you with a disk emulator on which to store

your filesystem. This "disk" is actually stored as one big file in the file

system, so that you can save data in a disk image and then retrieve it

later. In addition, we will provide you with some sample disk images that

you can experiment with to test your filesystem. Just like a real disk,

the emulator only allows operations on entire disk blocks of 4 KB

(Disk::BLOCK_SIZE). You cannot read or write any smaller unit than than

that. The primary challenge of building a filesystem is converting the

user's requested operations on arbitrary amounts of data into operations on

fixed block sizes.

The interface to the simulated disk is given in include/sfs/disk.h:

class Disk { const static size_t BLOCK_SIZE = 4096; void open(const char *path, size_t nblocks); size_t size() const { return Blocks; } bool mounted() const { return Mounts > 0; } void mount() { Mounts++; } void unmount() { if (Mounts > 0) Mounts--; } void read(int blocknum, char *data); void write(int blocknum, char *data); };

Before performing any sort of operation on the disk, you must call

Disk.open() method and specify a (real) disk image for storing the disk

data, and the number of blocks in the simulated disk. If this function is

called on a disk image that already exists, the contained data will not be

changed. When you are done using the disk, the destructor will

automatcally release the file. Opening the disk image is already done for

you in the shell, so you should not have to change this.

Once the disk is open, you may call Disk.size() to discover the number of

blocks on the disk. As the names suggest, Disk.read() and Disk.write()

read and write one block of data on the disk. Notice that the first

argument is a block number, so a call to Disk.read(0, data) reads the

first 4KB of data on the disk, and Disk.read(1,data) reads the next

4KB block of data on the disk. Every time that you invoke a read or a

write, you must ensure that data points to a full 4KB of memory.

Additionally, you can register and unregister a disk as mounted by calling

the Disk.mount() and Disk.unmount() methods respectively. The

Disk.mounted() method returns whether or not the disk has been registerd

as mounted.

Note that the disk has a few programming conveniences that a real disk would not. A real disk is rather finicky -- if you send it invalid commands, it will likely crash the system or behave in other strange ways. This simulated disk is more "helpful." If you send it an invalid command, it will halt the program with an error message. For example, if you attempt to read or write a disk block that does not exist, it will throw an exception.

File System

Using the existing disk emulator described above, you will build a

working file system. Take note that we have already constructed

the interface to the filesystem and provided some skeleton code. The

interface is given in include/sfs/fs.h:

class FileSystem { static void debug(Disk *disk); static bool format(Disk *disk); bool mount(Disk *disk); ssize_t create(); bool remove(size_t inumber); ssize_t stat(size_t inumber); ssize_t read(size_t inumber, char *data, size_t length, size_t offset); ssize_t write(size_t inumber, char *data, size_t length, size_t offset); };

The various methods must work as follows:

A.

static void debug(Disk *disk)

This static method scans a mounted filesystem and reports on how the inodes and blocks are organized. Your output from this method should be similar to the following:

$ ./bin/sfssh data/image.5 5 sfs> debug SuperBlock: magic number is valid 5 blocks 1 inode blocks 128 inodes Inode 1: size: 965 bytes direct blocks: 2

B.

static bool format(Disk *disk)

This static method Creates a new filesystem on the disk, destroying any

data already present. It should set aside ten percent of the blocks for

inodes, clear the inode table, and write the superblock. It must return

true on success, false otherwise.

Note: formatting a filesystem does not cause it to be mounted. Also, an attempt to format an already-mounted disk should do nothing and return failure.

C.

bool mount(Disk *disk)

This method examines the disk for a filesystem. If one is present, read the

superblock, build a free block bitmap, and prepare the filesystem for use.

Return true on success, false otherwise.

Note: a successful mount is a pre-requisite for the remaining calls.

D.

ssize_t create()

This method Creates a new inode of zero length. On success, return the

inumber. On failure, return -1.

E.

bool remove(size_t inumber)

This method removes the inode indicated by the inumber. It should

release all data and indirect blocks assigned to this inode and return

them to the free block map. On success, it returns true. On failure, it

returns false.

F.

ssize_t stat(size_t inumber)

This method returns the logical size of the given inumber, in bytes. Note

that zero is a valid logical size for an inode. On failure, it returns

-1.

G.

ssize_t read(size_t inumber, char *data, size_t length, size_t offset)

This method reads data from a valid inode. It then copies length

bytes from the data blocks of the inode into the data pointer,

starting at offset in the inode. It should return the total number

of bytes read. If the given inumber is invalid, or any other error is

encountered, the method returns -1.

Note: the number of bytes actually read could be smaller than the number of bytes requested, perhaps if the end of the inode is reached.

H.

ssize_t write(size_t inumber, char *data, size_t length, size_t offset)

This method writes data to a valid inode by copying length bytes from

the pointer data into the data blocks of the inode starting at

offset bytes. It will allocate any necessary direct and indirect blocks

in the process. Afterwards, it returns the number of bytes actually

written. If the given inumber is invalid, or any other error is

encountered, return -1.

Note: the number of bytes actually written could be smaller than the number of bytes request, perhaps if the disk becomes full.

It's quite likely that the File System class will need additional

internal member variables in order to keep track of the currently mounted

filesystem. For example, you will certainly need a variable to keep track

of the current free block bitmap, and perhaps other items as well. Feel

free to modify the include/sfs/fs.h to include these additional

bookkeeping items.

Implementation Notes

Your job is to implement SimpleFS as described above by filling in the

implementation of src/library/fs.cpp. You do not need to change any

other code modules. We have already created some sample data structures to

get you started. These can be found in include/sfs/fs.h. To begin with,

we have defined a number of common constants that you will use. Most of

these should be self explanatory:

const static uint32_t MAGIC_NUMBER = 0xf0f03410; const static uint32_t INODES_PER_BLOCK = 128; const static uint32_t POINTERS_PER_INODE = 5; const static uint32_t POINTERS_PER_BLOCK = 1024;

Note that POINTERS_PER_INODE is the number of direct pointers in each

inode structure, while POINTERS_PER_BLOCK is the number of pointers to be

found in an indirect block.

The superblock and inode structures are easily translated from the pictures above:

struct SuperBlock { // Superblock structure uint32_t MagicNumber; // File system magic number uint32_t Blocks; // Number of blocks in file system uint32_t InodeBlocks; // Number of blocks reserved for inodes uint32_t Inodes; // Number of inodes in file system }; struct Inode { // Inode structure uint32_t Valid; // Whether or not inode is valid uint32_t Size; // Size of file uint32_t Direct[POINTERS_PER_INODE]; // Direct pointers uint32_t Indirect; // Indirect pointer };

Note carefully that many inodes can fit in one disk block. A 4KB chunk of

memory containing 128 inodes would look like this:

Inode Inodes[INODES_PER_BLOCK];

Each indirect block is just a big array of 1024 integers, each pointing

to another disk block. So, a 4KB chunk of memory corresponding to an

indirect block would look liks this:

uint32_t Pointers[POINTERS_PER_BLOCK];

Finally, each data block is just raw binary data used to store the partial

contents of a file. A data block can be specified as simply an array for

4096 bytes:

char Data[Disk::BLOCK_SIZE];

Because a raw 4 KB disk block can be used to represent four different

kinds of data: a superblock, a block of 128 inodes, an indirect pointer

block, or a plain data block, we can declare a union of each of our four

different data types. A union looks like a struct, but forces all of its

elements to share the same memory space. You can think of a union as

several different types, all overlaid on top of each other:

union Block { SuperBlock Super; // Superblock Inode Inodes[INODES_PER_BLOCK]; // Inode block uint32_t Pointers[POINTERS_PER_BLOCK]; // Pointer block char Data[Disk::BLOCK_SIZE]; // Data block };

Note that the size of an Block union will be exactly 4KB: the size of

the largest members of the union. To declare a Block variable:

Block block;

Now, we may use Disk.read() to load in the raw data from block zero. We

give Disk.read() the variable block.data, which looks like an array of

characters:

Disk.read(0, block.Data);

But, we may interpret that data as if it were a struct superblock by accessing the super part of the union. For example, to extract the magic number of the super block, we might do this:

x = block.Super.MagicNumber;

On the other hand, suppose that we wanted to load disk block 59, assume

that it is an indirect block, and then examine the 4th pointer. Again, we

would use Disk.read() to load the raw data:

Disk.read(59, block.Data);

But then use the pointer part of the union like so:

x = block.Pointers[4];

The union offers a convenient way of viewing the same data from multiple

perspectives. When we load data from the disk, it is just a 4 KB raw

chunk of data (block.Data). But, once loaded, the filesystem layer knows

that this data has some structure. The filesystem layer can view the same

data from another perspective by choosing another field in the union.

General Advice

-

Implement the functions roughly in order. We have deliberately presented the functions of the filesystem interface in order to difficulty. Implement

debug,format, andmountfirst. Make sure that you are able to access the sample disk images provided. Then, perform creation and deletion of inodes without worrying about data blocks. Implement reading and test again with disk images. If everything else is working, then attempt write. -

Divide and conquer. Work hard to factor out common actions into simple functions. This will dramatically simplify your code. For example, you will often need to load and save individual inode structures by number. This involves a fiddly little computation to transform an inumber into a block number, and so forth. So, make two little methods to do just that:

bool load_inode(size_t inumber, Inode *node); bool save_inode(size_t inumber, Inode *node);

Now, everywhere that you need to load or save an inode structure, call these functions. You may also wish to have functions that help you manage and search the free block map:

void initialize_free_blocks(); ssize_t allocate_free_block();

Anytime that find yourself writing very similar code over and over again, factor it out into a smaller function.

-

Test boundary conditions. We will certainly test your code by probing its boundaries. Make sure that you test and fix boundary conditions before handing in. For example, what happens if

FileSystem.creatediscovers that the inode table is full? It should cleanly return with an error code. It certainly should not crash the program or mangle the disk! Think critically about other possible boundary conditions such as the end of a file or a full disk. -

Don't worry about performance. You will be graded on correctness, not performance. In fact, during the course of this assignment, you will discover that a simple file access can easily erupt into tens or hundreds of single disk accesses. Understand why this happens, but don't worry about optimization.

Shell

We have provided for you a simple shell that will be used to exercise your

filesystem and the simulated disk. When grading your work, we will use the

shell to test your code, so be sure to test extensively. To use the shell,

simply run bin/sfssh with the name of a disk image, and the number of

blocks in that image. For example, to use the image.5 example given

below, run:

$ ./bin/sfssh image.5 5

Or, to start with a fresh new disk image, just give a new filename and number of blocks:

$ ./bin/sfssh newdisk 25

Once the shell starts, you can use the help command to list the available

commands:

sfs> help Commands are: format mount debug create remove <inode> cat <inode> stat <inode> copyin <file> <inode> copyout <inode> <file> help quit exit

Most of the commands correspond closely to the filesystem interface. For

example, format, mount, debug, create and remove call the

corresponding methods in the FileSystem class. Make sure that you call

these functions in a sensible order. A filesystem must be formatted once

before it can be used. Likewise, it must be mounted before being read or

written.

The complex commands are cat, copyin, and copyout. cat reads an

entire file out of the filesystem and displays it on the console, just like

the Unix command of the same name. copyin and copyout copy a file from

the local Unix filesystem into your emulated filesystem. For example, to

copy the dictionary file into inode 10 in your filesystem, do the

following:

sfs> copyin /usr/share/dict/words 10

Note that these three commands work by making a large number of calls to

FileSystem.read() and FileSystem.write() for each file to be copied.

Tests

To help you verify the correctness of your SimpleFS implementation, you are provided with the following disk images:

Likewise, you are also provided a set of test scripts in the tests

directory that will utilize these disk images to test your file system.

You can run all the tests by simply doing make test:

$ make test

Testing cat on data/image.5 ... Success

Testing cat on data/image.20 ... Success

Testing copyin in /tmp/tmp.8mbVjt9XfO/image.5 ... Success

Testing copyin in /tmp/tmp.8mbVjt9XfO/image.20 ... Success

Testing copyin in /tmp/tmp.8mbVjt9XfO/image.200 ... Success

Testing copyout in data/image.5 ... Success

Testing copyout in data/image.20 ... Success

Testing copyout in data/image.200 ... Success

Testing create in data/image.5.create ... Success

Testing debug on data/image.5 ... Success

Testing debug on data/image.20 ... Success

Testing debug on data/image.200 ... Success

Testing format on data/image.5.formatted ... Success

Testing format on data/image.20.formatted ... Success

Testing format on data/image.200.formatted ... Success

Testing mount on data/image.5 ... Success

Testing mount-mount on data/image.5 ... Success

Testing mount-format on data/image.5 ... Success

Testing bad-mount on /tmp/tmp.BZoOChcGKj/image.5 ... Success

Testing bad-mount on /tmp/tmp.BZoOChcGKj/image.5 ... Success

Testing bad-mount on /tmp/tmp.BZoOChcGKj/image.5 ... Success

Testing bad-mount on /tmp/tmp.BZoOChcGKj/image.5 ... Success

Testing bad-mount on /tmp/tmp.BZoOChcGKj/image.5 ... Success

Testing remove in /tmp/tmp.p00nKXt3Ut/image.5 ... Success

Testing remove in /tmp/tmp.p00nKXt3Ut/image.5 ... Success

Testing remove in /tmp/tmp.p00nKXt3Ut/image.20 ... Success

Testing stat on data/image.5 ... Success

Testing stat on data/image.20 ... Success

Testing stat on data/image.200 ... Success

Testing valgrind on /tmp/tmp.Io2oaaqjD0/image.200 ... Success

Reads / Writes

Depending on how you implement the various functions, the number of disk reads and writes may not match. As long as you are not too far above the numbers in the test case, then you will be given credit.

Idempotent

The provided test scripts require that the provided disk images are in their original state. Therefore, if you make any modifications to them while developing and testing, you should make sure you restore them to their original state before attempting the tests. Since we are using [git], you can simply do the following to retrieve the original version of a disk image:

$ git checkout data/image.5

Demonstration

As part of your grade, you will need to present your file system to

a member of the instructional staff where you will demonstrate the

correctness of your FileSystem class.

Documentation

As noted above, the Project 06 repository includes a README.md file

with the following sections:

-

Members: This should be a list of the project members.

-

Design: This is a list of design questions that you should answer before you do any coding as they will guide you towards the resources you need.

-

Errata: This is a section where you can describe any deficiencies or known problems with your implementation.

You must complete this document report as part of your project.

Design and Implementation

You should look at the design questions in the README.md file of the

Project 06 repository. The questions there will help you design and plan

your process queue implementation.

Feel free to ask the TAs or the instructor for some guidance on these questions before attempting to implement this project.

Grading

Your project will be graded on the following metrics:

| Metric | Points |

|---|---|

Source Code

|

20.0

|

Demonstration

|

2.0

|

Documentation

|

2.0

|