Notre Dame Legends and Lore / by Dorothy V. Corson

Every archival treasure needs a reason to surface, and the author’s interest in Indians on campus before the arrival of Father Sorin, the founder of the University of Notre , was that reason. The presence of a huge sycamore on the Grotto lawn -- reputed to have been there in Indian times -- prompted a side search to establish its age by looking for any information associated with Indians on campus in the university archives.

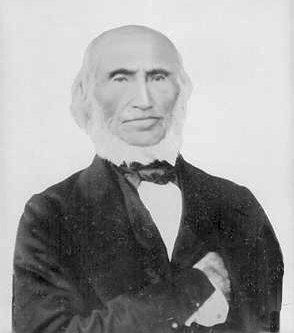

In the midst of my grotto research, Peter Lysy, one of the university’s archivists, ran across a transcription of the diary while filing something else and kept it out for me to look at. As a result of that good fortune, a German Missionary’s diary written before Sorin’s arrival describes in detail the original log chapel at Notre Dame which also served as his lodging. The diary also describes an Indian baptism in St. Mary’s Lake, a visit with Mrs. Coquillard and the missionary’s walk to Bertrand, Michigan.

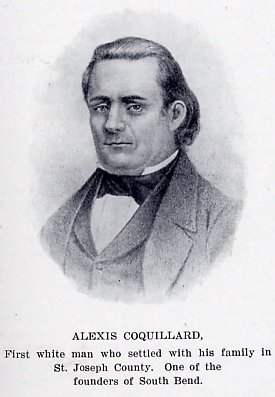

The above portions of the diary about Notre Dame are detailed in A Cave of Candles, Chapter 22a,“An Archival Treasure.” The segments that follow are from the last portion of his diary dealing with Michiana -- upper Indiana and lower Michigan. In these last two segments he describes the general Michiana area in this case, St. Joseph Valley and Bertrand, Michigan. This first segment describes the lay of the land in 1840-41 and the role the men like Alexis Coquillard, an Indian Trader, played in developing the town of South Bend, as one of the founders.

The second segment, “A Walk to Bertrand,” describes the high hopes and hard times and illnesses the settlers had endured and were still enduring during the time the missionary visited Bertrand, which occurred a year or two before Sorin’s arrival at St. Mary of the Lake in November of 1942. The University of Notre Dame and its faculty and students would go through this same “trial by fire” during an epidemic of Cholera that swept the region in the 1850s.

This archival gem surfaced after being hidden away in a file for 30 years. Lysy found it just in time to be included in my A Cave of Candles manuscript. How this diary wound up in the archives is another interesting story. In 1972, the Indiana Historical Society was cataloging some of its materials. It was then that Caroline Dunn, the historical society’s librarian at the time, discovered a book written by an unidentified German missionary priest.

The 296-page book recounted his travels through Canada, New England and the Midwest -- including his experiences in the Michiana area. Dunn, asked if the Notre Dame archives had a copy. The missionary’s description of the Interior of the original “mission house located at St. Mary of the Lake” and its surroundings speaks for itself. This area would eventually become the site of the University of Notre Dame.

The diary was translated from German by Erik Dix, an archivist at the University of Notre Dame Archives. Readers may find some of the terms and the writer’s viewpoint, which was common more than 150 years ago, objectionable.

In the first of the two last segments of the German Missionary’s diary he speaks of Alexis Coquillard, the fur trader, and co-founder of South Bend who tells him of the restless life led by many of the men of his day who traded with the Indians:

The little town, like most of the larger settlements in America, looks very new and youthful, but despite its great distance from the Atlantic harbor-towns has several stores, in which all luxury articles are available, to keep up in the western wilderness with the customs and habits of the rich New Yorker. The inhabitants of South Bend are for the most part Anglo-Americans, who for the most part profess Methodism or sentimental religion.

Only a few families of my faith [Catholic] are living there, and I had a hard time finding them. Fairly well known, however, is the family of Coquillard, a French Canadian, who has a magnificent house with an extended estate in the northern part of South Bend. He was a trader among the savages and became so rich doing this that he could build a palace-like residence in a marvelous area and buy a large adjacent stretch of land. I stopped off at this house without reservations, was met with a friendly reception, and was treated during my stay with the utmost attention. (A pleasant reflection of the golden times of our holy religion, where Christians were always welcomed by their fellow believers.)

Such a comfortable and splendid estate as the one of Mr. Coquillard is only bought by traders. Many of them grow so fond of their wandering in the primeval forests among the Indians that they donít like the stable and domestic life anymore, even if they amass a great fortune. Used to the hardships and dangers of life, the quiet and secure mastery of things appears to them to be too dull to sustain. For that reason, when soul and body have always been at work, the lasting calm of standing still makes both sick.

Mister Coquillard introduced me to one such restless trader. He speaks Canadian French and a little English and understands the languages of several Indian tribes, particularly that of the Potawatomis; for more than 12 years he has been married to a wild Indian woman. He dwells with her among the Potawatomis, living their way of life, dressing in a manner only a little more European than theirs.

His wife, a big, enormously strong woman, had a pretty good laugh when the old gray Canadian was making some boyish jokes for us, at the same time negotiating with my host over some hides that he brought from his forests. Mister Coquillard, who negotiated as the American government’s agent for Indian affairs, offered him, who is cultivating himself for savagery, 300 dollars a year to stay with him as his assistant agent. But the strange Canadian prefers to disport himself in the primeval forest with his fat and not at all beautiful squaw and to fast severely, sometimes for several days, when there is nothing to eat. That is how it is to be human!

The cultivated toil away to civilize the savages, and the civilized toil away to run wild again. But this is not the only example. In the history of Canada we find several considerable aristocrats, well raised in Europe, who let themselves be accommodated as comrades by the Indians along the St. Lawrence River, and remained with them.

The sister of an Englishman living in America had been kidnapped in her early youth by Indians and had been raised by them. Through an extraordinary coincidence the sister has been found and recognized by her cheerless brother after many years. The joy of the reunion didnít last very long, because the sister could not be induced through any pleading or begging to return with her brother to her relatives in the civilized world. She stayed with the savages!

Also the British captain Marryhat tells in his diary how he met a formerly very educated European who settled with the Indians and even became one of their war chiefs.

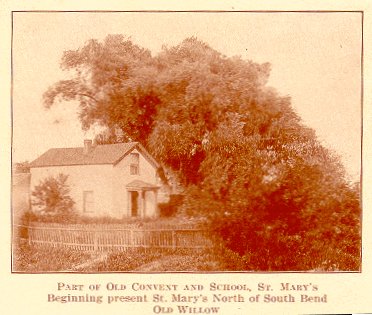

In “A Walk to Bertrand, Mich., ca. 1840,” the German missionary speaks of his visit to Bertrand and how he was sent there from Detroit to “celebrate Easter” in the mother tongue of the Germans living in the vicinity. Their district priest was unable to speak German. In this segment, he gives an account of his walk to Bertrand, Michigan, and the people he met before the Sisters of the Holy Cross founded their school there. With the assistance of Father Sorin, St. Mary’s Academy was later moved from Bertrand to Notre Dame, Indiana where it was destined to become Saint Mary’s College.

Because the distance from St. Mary of the Lake to Bertrand only amounted to several miles, I set off on foot, breviary in one hand, my umbrella, which also served me as a sunshade, in the other. I had already passed the hill at the lake, which I described to you at the “Indian Baptism,” and I was about to turn in an open woodland towards my destination, when I suddenly heard a far sounding, piercing whistle, which I recognized immediately in its peculiarity as the communication signal of the savages.

Had I been in a different region where pagan, really wild Indians lived, I would not have heard this whistle with total peace of mind but as something pernicious, because this characteristic Indian whistle, which sets the teeth on edge, is normally a signal to attack, at which they, in their cunning, suddenly fall upon their chosen human sacrifice and hand it over to their cannibalistic desires. This time I wasn’t in danger; the whistle surprised but didn’t frighten me. And when I looked back to where the piercing sounds came from, I noticed a tall, handsome Indian figure under a tree on the hill. I understood the Indian when he saddled a horse and indicated that I should use it.

Since I didnít have the essential missionary ‘art’ of riding well, I would have preferred, of course, to continue my journey on foot, rather than entrust myself to the brave, big Indian nag -- but I didnít want to offend the good-hearted savage, who certainly would have considered my refusal of his offer an indication of low regard for his helpful respect towards the ‘Father;’ for that reason I returned and mounted the horse he offered.

After a long ride through the impressive remains of a great primeval forest, I arrived safely in Bertrand. The Indian’s noble-minded animal didn’t take revenge for my riding skills, and behaved itself very gently despite its impetuous character.

Bertrand is a little, newly constructed village founded by the French (or half-breed) Canadian Bertrand in the southwestern part of the State of Michigan near the St. Joseph River.

Even though Bertrand had been laid out splendidly in its plan, so far it hasnít grown to an important size, for which malaria, which was causing its own kind of havoc under the name of “Michigan fever,” was particularly responsible. It is true that the newly plowed soil of land that has to be cultivated releases a certain toxic substance all over America, which, through various diseases, reverses the ignorant and incautious immigrants’ earlier ideas of happiness; but in some regions this toxic substance appears more frequently and more severely, particularly where water is scarce during the summer; during the winter the water of the river can be used until warmer times of the year. With the aging of the cultivated new soil even this evil of the first settlements will probably disappear; but what good does this do for the already sick or even deceased countryman? In Bertrand the fever raged horribly in those days; I still met several sick people, who gave terrible accounts of the misery in which they recently lived -- in many houses whole families laid low, helpless until another sick person, who pulled himself together sooner, came from the neighborhood, and could attend the abandoned sufferer a little bit.

Even though Bertrand had been laid out splendidly in its plan, so far it hasnít grown to an important size, for which malaria, which was causing its own kind of havoc under the name of “Michigan fever,” was particularly responsible. It is true that the newly plowed soil of land that has to be cultivated releases a certain toxic substance all over America, which, through various diseases, reverses the ignorant and incautious immigrants’ earlier ideas of happiness; but in some regions this toxic substance appears more frequently and more severely, particularly where water is scarce during the summer; during the winter the water of the river can be used until warmer times of the year. With the aging of the cultivated new soil even this evil of the first settlements will probably disappear; but what good does this do for the already sick or even deceased countryman? In Bertrand the fever raged horribly in those days; I still met several sick people, who gave terrible accounts of the misery in which they recently lived -- in many houses whole families laid low, helpless until another sick person, who pulled himself together sooner, came from the neighborhood, and could attend the abandoned sufferer a little bit.

Little children often provided the nursing for their relatives until they themselves were thrown on the sickbed (if there was still a bed available). Very many died of this fever, and the new looking village of Bertrand gave the impression of a deserted town ruin. A good many people who have a craving for immigration, who have their good income in their old home country, would be cured of their wanderlust, if they could see in advance the four to five year long struggle, through which the immigrant has to put himself in America, if he doesnít want to expose himself from then on to an undetermined position in relation to his livelihood.

But the soil in and around Bertrand is very fertile and is excellently suited for productive growing of wheat; one who has luckily survived the first hard time of test and struggle can live afterwards without lack of food. But besides the mortal body the immigrant also has an eternal soul and an immortal spirit, which in the loneliness of the new world, in the distant west, for example, are crying far more impetuously and tormentedly for the satisfaction of their hunger than in the old world, in Europe.

Didn’t I have to make a trip from my mission station of more than 500 English miles to get to German immigrants, who had already signed for seven years for a priest who knows how to console them in their mother tongue?

Mr. Bertrand’s wife is an Indian of the Potawatomi tribe, -- a good-hearted soul, who has been much refined through Christianity. She is the total opposite of her husband, who obtained considerable lands through her. The children of this marriage might have adopted the outer coat of civilization, but the traditional life in the woods shows everywhere through the modern city clothing. The sons are married to Anglo-American women, whose children also still have the darker skin of the Indians, which unpleasantly contrasts with the snow-white delicate skin of their mothers. The younger Bertrands also speak French and English, besides the Indian Dialect of their mother, and are rendering great service as translators between missionaries and the Indians. Their sisters are playing ‘Ladies;’ they look in their European outfits, compared to their mother dressed in plain Indian clothes, like strange growths on the family tree.

What a good many painters would have given if they could have been in my place to study the peculiar characteristics that emerged from this strange mixture of people in the Bertrand family.

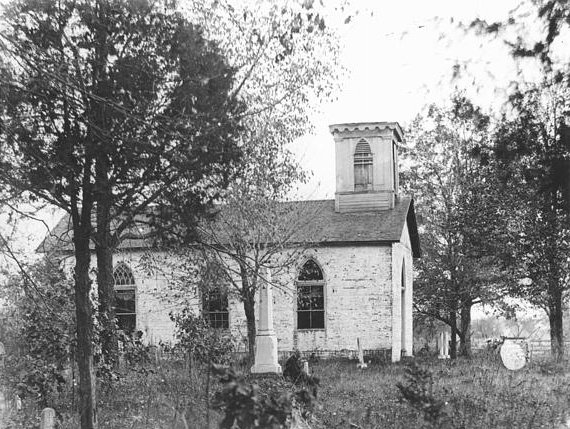

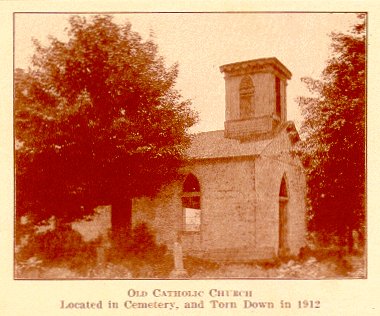

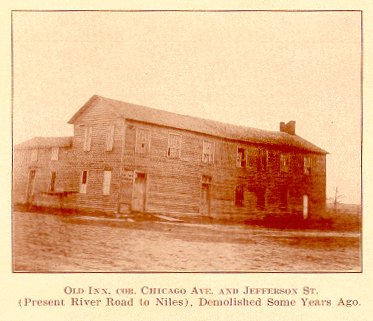

This is the last segment about Bertrand from the German missionary’s diary. Here he speaks of the people he met in Bertrand, south of Niles, and the sermon he gave in the mother tongue of the German settler who had waited many years for the arrival of a German missionary. All that is left now of the once-thriving town of Bertrand is the house that was part of the old convent where St. Mary’s Academy was founded, the foundation of the little brick church, and its neglected cemetery.

Bertrand hasn’t been so lively and full of visitors for a long time as on that day, and for that reason I received more than one compliment from the local residents.

During the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, which I said before the sermon, I gave communion to the German Catholics and then to a great horde of Indians, who had been prepared for it the day before.

They had spruced themselves up for the spiritual wedding meal; their woolen blanket wraps were freshly washed, their shirts underneath were clean, all damages on the leggings and moccasins had been carefully repaired. Most of the men had colored scarves wrapped around their heads; the squaws pulled their woolen blankets, some of which were embroidered with artistic hem stitches, over their heads from their backs to their foreheads and held them together under their chins with their hands.

As fantastically as some of these Indians had adorned themselves, wrapping many decorations around them, not one of the curious people present in the church tried to laugh, because they could see at the same time the decency and respect with which the converted ‘savages’ were going to celebrate the mysteries of their holy religion. As they finally approached the communion rail at the altar and fell down on their knees to receive in the holy form of bread the highest Lord of Heaven and Earth, all people present, whatever their religion, were visibly touched. But I myself, who had to look directly into the face of the Indians, was deeply touched, so much that I could hardly hold the chalice.

At noon I ate with all the Germans, who had done their Easter duty in the morning with me at the same table, in the restaurant of a man from the black forest, Mister Mezger; it was a truly loving feast, as I had never experienced before.

I refrain from all sentimental remarks about this mission, which was connected with a very burdensome trip. Every reader will easily guess what was happening in my heart at this scene in the field of religion, as it made me quickly forget all struggles; the recollection of it still fills me with gratitude towards Him, whose mysterious paternal rule over all men on the whole earth becomes apparent.

Dorothy V. Corson

April 5, 2003

*Skizzen aus Nord-Amerika (Augsburg 1845), description of the Michiana Area, ca. 1840, Indians of North America Printed Material (PP0T) University of Notre Dame Archives. English translation by Erik Dix, archivist at the University of Notre Dame Archives

An extraordinary detailed description of Badin’s original Indian Chapel and its surroundings was penned by this same German Missionary in the form a transcribed journal of letters to his European Doctor friend during a stay at Badin’s original Log Chapel in 1840.

He describes in vivid detail, the Log Chapel interior, the Indians camped at the lake, the services he held for them, and the baptism of a newborn Indian baby in St. Mary’s lake in this excerpt from his diary:

-- German missionary’s description of his stay

in the Log Chapel in 1840.