A Cave of Candles / by Dorothy V. Corson

Chapter 22a

An Archival Treasure Surfaces

Peter Lysy, the archivist, walked up to me one day holding a folder in his hand. "I ran across this while I was doing some cataloging," he said, I thought it might interest you. I thanked him, tucked it under the folder I was working on and made a mental note to check it out before leaving for the day. Several hours later, I opened the folder, read two pages of it and went looking for Peter. "Where did you find this gem," I asked him! He grinned at me and commented, "I thought you'd dig it!"

For almost a year, I had been searching every available source looking for early references to Indians on campus to confirm the legend. Now, when I thought I had exhausted all avenues open to me, the unexpected, once again, landed in my lap. The transcribed journal of a German missionary priest who visited the mission of St. Marie des Lacs. He describes in detail the log chapel, the Indians camped by the lake, and the events that transpired during his stay.

I had events concerning Indians after Sorin's arrival, now I had my first on-the-spot impression of the Badin mission before Sorin arrived. It was a word picture that begged to be included. The journal was published in 1845. It is believed to have been written sometime around 1840 or 1841 before Sorin's arrival in November of 1842. It begins with a very detailed description of the log chapel and the Indians through the eyes of a visiting missionary priest very impressed with his surroundings. In part:

The Missionary Lodging

I am writing these lines to you in a log cabin on the elevated bank of a small, quiet lake in northern Indiana, on the southwestern border of Michigan, close to the St. Joseph River . . . .

A small, quiet lake . . . like a magic mirror throws back to the observer the vault of heaven above it and the friendly environment around it . . . .

[On its] banks some noble friends built a log cabin several years ago, in which I now dwell.

. . .

The lake in front of me is situated in the cold even in the greatest heat, in mind-freezing North America; the fire behind me has been raked by a semi-savage Canadian, and the bell-ringing comes from the necks of horses belonging to a group of Indians of the Potawatomi tribe who have put up their temporary camp at the lake; the log cabin itself in which I am putting together this letter to you is the mission house of St. Mary of the Lake (Ste.-Marie-du-Lac).

So that you can get an idea of an American mission house, I will let you see first the lodging of the missionary. It is a simple room in which you will look in vain for mural paintings or wallpaper, stucco work and frescos. The four walls of the room consist of roughly cut logs; one wall is formed by a enormous fireplace. The two windows, which face each other, have no mechanism to allow them to open, but accidents have provided openings in the glass through which the air can come in and out. The curtains -- even the most wretched hut in North America, such as the one of the missionary, has to have "Curtains" -- do look shabby, but the bed and its covers and curtains are even shabbier; yet they look pretty cheerful in this poverty. There is a canopy, like the kind of wooden four-poster covers our grandparents used to have, to keep outbreaks of the elements of earth and water away from the sleeping apostle of the Indians, because the boards of the roof are not joined together closely enough to have sufficient security against the weather.

In order to keep the missionary from losing his courage in this American forest abbey, the poor cabin is adorned inside with the sign of triumph of the One Who is the Way, the Truth and the Life, who didn't even have a place where He could rest his head.

If you were standing next to me in person, you would already have cast your eyes on the surprising abundance of books, which you surely wouldn't expect to find with a "Blackrobe" in such a wasteland among the Indians.

Not only Missals and books of Psalms, Bibles in several languages and church fathers, but also the old spiritual heroes from Athens and Rome, as well as the new ones from England and France -- not only put up here, but also, as you could convince yourself by a closer leaf through, frequently used. You can't expect German books here, because the former occupants of this cabin emerged from French schools at a time when even in Germany the German language was neglected and despised.

The House Chapel

Go up with me now to the upper part of the mission house. The stairs are not very comfortable, -- the way to heaven is onerous. So -- one more wooden step and you are in the chapel.

The garret has been changed into a very friendly oratory, where at present the divine service is celebrated also, because the old chapel on the ground couldn't escape the frailty of old age and its repair has been postponed for lack of means.

Now look around the temporary chapel until I have changed for the divine service, because the regular priest of this house, a Frenchman born in Canada, is traveling and asked me to celebrate in his place.

There on that side of the attic chapel where the altar table is set up for the offering, the wall is covered tastefully with freshly washed linen, on which fresh green cedar twigs from the trees of the primeval forest at the lake have been arranged ingeniously; through the striking white of the linen it distinguishes itself as the almost sublime work of an artistic weaver.

The Madonna picture, engraved copperplate, simple but good, and very big, symbolizes the humility of the mother of our redeemer, and looks down, fair and lovely, from the linen-forest wall covering, and makes you feel quite religious. A wooden cross is standing on the simple altar, which faith in the Crucified brought over the wide ocean, between two simple candlesticks which have been sent over by good-hearted people from Europe. The flowers of the nearby prairie in the not very graceful pots between the candlesticks go well with the whole scene.

If you have looked at the religious part of the chapel, turn around and see how the sturdy children of nature from the north of America, natives of the Potawatomi nation, sit on their tree stumps and silently wait until the divine service starts.

It is a miracle how these rough seats could have been brought up the frail stairs, an even bigger one is how the thin wood floor can support these wood blocks with Indians sitting on them.

Admire the sturdy physique of these "Savages" with their long, jet-black hair, protruding cheek bones on upward-tapering oval skulls, and deep, dark, expressive eyes, which you can come across in Europe only in very soulful people.

Some among these Indians have piercing, frightening facial features, which would frighten at first sight, if we weren't convinced that these people have already accepted Christianity, have thrown away their axe and scalping knife, and use bow and arrow only for hunting game to make their living.

You see how many of the children of the forest present have in their hands prayer books printed in their language, with which they constantly follow the priest in his ceremony at the altar, as their faces light up with inspiring faith in the Savior of the world. Don't miss how I, the poor servant, am honored and loved by them because of the great Master, and asked for frequent blessings. How does the expression NOSE (Father) sound, with which they address their priest? It is so indescribably winning! They, formerly animal-like, live now in the greatest modesty with the scantiest clothes on their body and a woolen blanket as their outer garment, happier and more content than most of the rich in the most progressive cities in Europe, who try to think about the work of faith with the rational intellect.

Those men have to be praised very highly, who have struggled with the greatest troubles in this house I have introduced to you, to carry out their plans to cultivate these wild people.

Mr. [Father] De Seille, the son of very highly regarded parents in Belgium, is resting from all his struggles and sufferings in the old chapel ground near this mission house. In the house where he so often broke the bread of eternal life for the Potawatomis, and fed them with the food of the angels, nobody was present at his death who could have provided the last rites to him. Before he passed away he crawled with the greatest effort to the altar in the small chapel and refreshed his soul for the last time with the consecrated bread.

[Father] Petit, formerly the famous lawyer and popular speaker at Rennes (Ille-et-Vilaine) in France, after half a year of his presence in the same house, preached in the language of the Potawatomis; and then, as a victim of the purest humanity on an onerous trip which he made with the savages across the Mississippi to St. Louis, a city on that river, he was physically defeated, only to celebrate his resurrection in the hereafter all the more victoriously.

But now it is time that I say Holy Mass; the Indians are waiting for it. They came here from a great distance to celebrate the requiem for their missionary (Petit), who accompanied their tribesmen in their exile [their forced march to Kansas] and died on the way back. [He was 28 years old.] Now I ask you, as soon as I am dressed for the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, to behave yourself properly; don't look around, and be devout. And if you hear a rising, loud murmur during the main part of the Sacrifice, do not fear.

This is . . . an outpouring of faith in the holy mystery of the religion that penetrates them, to which they are now so loyally devoted that they, since baptism, have stood clear of any grave offense against godly and generally applicable human laws.

A Visit with Mme. Coquillard

The missionary priest goes on to mention a visit to the nearby home of Mme. Coquillard. He describes his admiration for the young Indian he meets there.

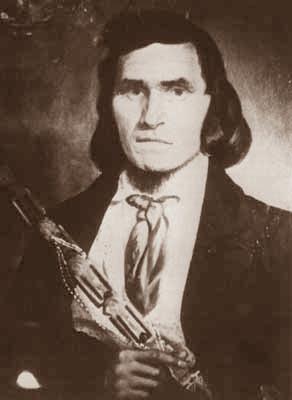

During my stay in South Bend I was sitting one morning in the Coquillard family's parlor and talking with the little son of the household when suddenly a handsome, slender, young Indian came in. The strongly built child of the forest came into the room with dignity and moved freely and without inhibition on the expensive carpets of my friend's parlor, as if he was always used to the luxury of refined England. . . . The young Indian was very well dressed: He wore perfectly tight-fitting leggins -- that means "leggings" or a kind of two-part trousers worn like long stockings and tied to the hips with string. These leggings were decorated on the outside with a wide border that stuck out a little. Over them a clean shirt hung down to the knees, fastened with a leather belt around his hips like the dust coats of our students. In his belt he had a bowie knife and on his feet he had fine moccasins (Indian shoes) cut from soft deer hide, like tobacco pouches in the shape of feet, sewn together only on the instep. Because of its lightness and softness this kind of shoe is very beneficial for the silent walk of the quick-footed, cunning savage.

The moccasins of this young Indian were moreover decorated with embroidered leather trimmings, which covered the ankle and almost the whole upper part of the shoes. Such was the squaw's embroidery; nobody would expect such neat needlework from savage Indian women. His well formed head was bare; his shiny black hair was combed from the front to the back and fell down his neck; his glowing jet black eyes were focused on me, the "Father". (With "Nose", Father, as I already mentioned, the converted savages address the missionary.) And as he stepped closer to the Father with graceful posture, he knelt down to receive the blessing of the "Blackrobe" and asked me to accept the present which he presented in the name of the Indian band that had sent him. It was a very big, just recently shot, and already totally cleaned turkey . . . .

It is after this description -- in recording a sad story of another young Indian told to him by Mrs. Coquillard -- that he touches on the very subject I had been wondering about, the explanation of the Indian belief in revenge which in turn explained why the landmark sycamore was called, The Vengeance Tree. In relating the story to him, she also explains the Indian belief in justice. Mme. Coquillard, who was reputed to be part Indian, was an interpreter for Badin, DeSeille and Sorin.

The incident she related to him was reminiscent of the legend of the sycamore tree:

When Madame Coquillard noticed my obvious admiration for the handsome build and fine figure of an Indian young man, she told me that not long ago in the vicinity one such well built young Indian had been killed by his own grandmother. The young man had killed an Indian from a different tribe in a state of great excitement. Shortly after the crime had happened, the murderer regained consciousness and, knowing well that according to pagan Indians' laws of vengeance, his life became forfeit to the family of the murder victim, he fled and disappeared. The vindictiveness in the hearts of the Indians, where the power of Christianity hasn't reached yet, is unbelievable. If they die before they can get hold of their desired victim, they leave the execution of the revenge plan as the holiest tradition for their offspring, which they couldn't carry out because of the lack of opportunity. So unsatisfied feelings for revenge pass on to several generations. Now the family of the murder victim demands from the family of the murderer a reconciliation sacrifice, which cannot consist of anything other than the extradition of the murderer himself or another member of his family related by blood. If a relative of the murderer had surrendered himself, the shame of the murder and on top of that the shame resulting from his weakness of character, because of the penance he failed to do, would have remained on his head, and even his relatives would have looked upon him as an outcast. Considering all this, the grandmother of the murderer knew how to lure her grandson out of his hiding place, and they met in the vicinity of Mr. Coquillard's house.

The grandmother, a strong, vigorous Indian women, now told her grandson, since he had to die, it would be more honorable to be killed by her than to die the death of revenge under the humiliating hands of the enemies who were pursuing him -- and saying this, she stuck her knife in the chest of the unsuspecting young man. The grandson quickly breathed his last, and the grandmother's barbaric sense of honor was satisfied. But now nature also claimed its rights towards that woman. As she saw the young man lying on the ground in his blood, she raised such an outcry of lamentation and such howls of mourning that the stones of the valley and the trees of the forests asked to mourn with her. She fell down on the grandson, tearing her hair, pounding her chest, stamping her feet on the ground on which the corpse was lying. This severe pain passed into a frenzy which lasted almost a whole day. The other relatives also came by and helped to complete the dreadful picture of furious agony. A messenger was sent to the family of the murder victim by the family of the grandson -- the reconciliation had been accomplished. "This scene of agony," said Mrs. Coquillard, "is always fresh before my eyes; the impression she had on me is indelible. I was suffering badly and couldn't at all get the howls of mourning out of my ears. Thanks be to God, who sent the missionaries to relieve them from such scenes."

The visiting priest explains how Christianity was transforming the Indians' attitude toward vengeance:

At this remark, I myself appreciated the divinity of the Christian faith, which is capable of making gentle children and lambs out of brutes and hyenas. Indians, even the most frantic men, give up their vindictiveness, which had been part of them for all times, once they have sworn allegiance to the banner of Christ.

. . .

These wild children of nature with their otherwise sharp and glaring physiognomies had now with the enjoyment of the Lamb nothing but faces of saints. Their black eyes bathed in tears, which rolled down their copper red cheeks in big and heavy pearls; a kind of transfiguration was poured out across their faces, which showed the pagans the power of the faith and showed the faithful the inner sun of grace, which shone out of the hearts of these inhabitants of the forest who had been innocent since their baptism.

A greater humility, a higher decency, a firmer faith and a deeper worship can hardly be found anywhere than in these natives of America in the church at Bertrand, which became apparent to the astonished and ashamed descendants of Europe. This edifying behavior of the Indians also prevented them from being derided and ridiculed by the different-minded residents of Bertrand, when they knelt in front of the priest to receive his blessing if they met him somewhere in the village, which they did with a special trust in the "Great Spirit".

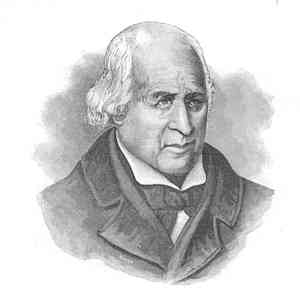

A striking example of the influence of the early missionaries in this regard is the description of such an incident related by Badin himself when he first came to St. Marie des Lacs and which he sent by letter, as requested, to the Bishop:

The late good Bp. Fen[wick] of Cincin[nati] having desired me in May last, to give to the Ind[ian] Department occasional information of considerable events and other subjects respecting the tribe among whom I reside, I shall begin relating the circumstances incident to a murder which took place last Spring, soon after my return from Cincinnati.

On the 9th day of last June, Topinabee, a man of about 25 years of age, chief of the whole tribe of the Pout., who would not listen to religion, did in a drunken fit kill Nanankoy, a man justly esteem'd in the nation -- The murderer surrendered at a council held at Carey on the 11th June and looked with resignation for the punishment with the drawn and glittering knives of the brother and friends of Nanankoy

A sinister silence followed after some peaceful speeches of Pokagon [an elder Chief of the Potawatomi]. My interpreter [Angelique 'Liquette' Campeau], an old woman of 68 years of age, much respected and beloved by the Indians, after unsuccessful attempts to avert a vengeance, which probably would have provoked many other murders, disarmed the men by generously offering her own life in these words addressed to the sullen and indignant brother of the deceased. "Kill me, I stand here to be killed in lieu of Topinabee."

The brother stunned by this unexpected effort of charity, consented to delay inflicting the deadly blow and having been also brought by the Agent (Col. Stewart), from council to a private conversation he resolved to refer the decision to a certain chief, his near relative and to a pretended prophet on the Wabash who gave a bloody answer. But before coming to the dreaded execution several long talks were held with me where I made them so sensible that the prophet was not the son of God as he pretended to be that they laughed at his impostures and their own credulity. Finally a council was held on the 29th June, to whom I addressed the following letter, and it was agreed that Topinabee would be redeemed by making certain presents to the family of the deceased. All the red with some white brethren contributed to assist the chief in paying the price of redemption. -- It may be remarked here that Topinabee had come to me on the 17th June fallen [fell?] on his knees [and] promised me in the presence of God to drink no more whisky and he has been faithful to his promise.

Following is the speech on the evils of whiskey and the futility of killing Topinabee which Badin delivered to those assembled at Carey Mission, Niles MI on June 29, 1832:

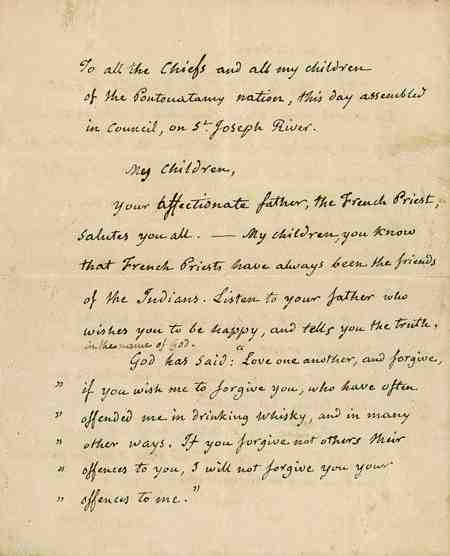

To all the Chiefs and all my children of the Poutouatamy nation, this day assembled in council, on St. Joseph River.

My children, Your affectionate father, the French Priest, salutes you all, -- My children, you know that French Priests have always been the friends of the Indians. Listen to your father who wishes you to be happy, and tells you the truth, in the name of God.

God has said: "Love one another, and forgive, if you wish me to forgive you, who have often offended me in drinking whisky, and in many other ways. If you forgive not others their offenses to you, I will not forgive you your offenses to me."

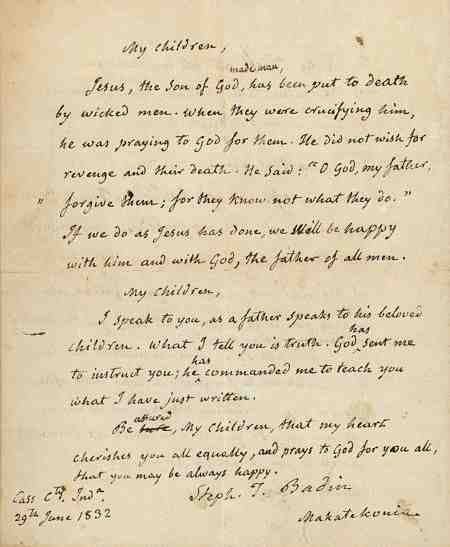

My children, Jesus, the Son of God, made man, has been put to death by wicked men. When they were crucifying him, he was praying to God for them. He did not wish for revenge and their death. He said "O God, my father, forgive them; for they know not what they do." If we do as Jesus has done, we will be happy with him and with God, the father of all men.

My children, I speak to you, as a father speaks to his beloved children. What I tell you is truth. God has sent me to instruct you; he has commanded me to teach you what I have just written. Be assured, my children, that my heart cherishes you all equally, and prays to God for you all, that you may be always happy.

Cass Cty. Inda.

29th June 1832

Steph. T. Badin

Makatekonia

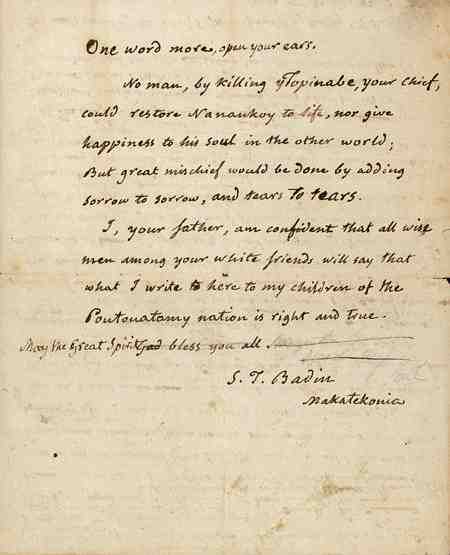

One word more, open your ears.

No man, by killing Topinabe, your chief, could restore Nanankoy to life, nor give happiness to his soul in the other world; But great mischief would be done by adding sorrow to sorrow, and tears to tears.

I, your father, am confident that all wise men among your white friends will say that what I write here to my children of the Poutouatamy nation is right and true.

May the Great Spirit bless you all.

S.T. Badin

Makatekonia(268)

This impressive document, the original of the above letter, is preserved among Father Stephen T. Badin's papers in the University of Notre Dame Archives. A testament to the early French missionaries' care and concern for the welfare of the Native American Indians who relied on their revered Blackrobes for Christian counsel.

Father Badin wrote of his interpreter, Angelique, whose actions saved the life of Chief Tobinabee: ". . . I do not know of a priest more industrious, more penitent, more patient, more learned, more genuinely pious then she is in all this country" [Quoted in Buechner, The Pokagons, page 302].

An Indian Baptism

The visiting German priest goes on to describe an Indian baptism he performed at St. Mary's Lake during his visit there:

Near the mission house, whose interior I have briefly described for you already, a little hill rises, in the shape of a mountain ridge, which extends in a straight line for several hundred steps, and faces with its precipitous side the lake with which I made you acquainted in the first chapter of this letter.

On this ridge now you see several tents made from rush mats, pitched in the simplest way. In front of them you still see the smoking ashes of their fires, on which the "redskins" prepared their meals in the gypsy way. The men, having said their prayers in the chapel of the wilderness, now stroll around in the temporary camp altogether carefree and unconcerned about the activities of the neighborhood, and puff away on their pipes with wonderful manners. The squaws, the born Cinderellas in the family life of the natives in America, are industrious and active in their traveling household, and clean and tidy up the pieces of their household possessions, which are easily counted. The little savages, for want of a bathtub, get their morning refreshments in the lake, while the older boys are following the horses in puris naturalibus, which, hobbled at the bottom of their front legs, can only hop like frogs, but while doing so take their fill of lush prairie grass in the broad meadow on the banks of the lake. Walk now with me up the hill, where I will baptize an Indian born this morning. I will celebrate the baptism in front of the tent where the mother of the child is. She came yesterday riding à la Turc with the Indian train and is lying now fresh and healthy under the rush roof. She is wrapped tightly into a woolen blanket and of her body only the head with its long black hair and glowing eyes is visible. Her whole situation brings instinctively back to my mind the Egyptian mummies I have seen, even more so since her glance is focused on me without movement. In the tent everything is unusually clean, though nothing remains so that you, as a doctor, will be reminded of the delivery that took place here only a few hours ago. A plain mat has been spread out for me in front of the tent; the beautiful blue sky is arching above me like a dome made from lapis lazuli; the clear surface of the lake reflects the cheerful splendor of the sky; the manifold greens of the nearby bushes, like the fine cedar, tulip, and oak trees of the forest on the opposite side, decorate the lake, which now is viewed as the font; and the grass slope with its decoration of far-western flowers, which stretches all the way to the lake, serves as the carpet of the imposing house-chapel in God's wonderful temple of nature.

To a small tree next to me in front of the Indian mother's tent I am fastening a Crucifix, sign of eternal salvation and highest "humanity", which I used to carry with me on my trips. So the little tree at St. Mary of the Lake becomes a beautiful symbol of the tree of deliverance and reconciliation, which would solemnly enable the son of the wilderness to participate in it through baptism. The baptismal water is ready; the white child of the redskin rests on the arms of its godfather; a group of Indian faces surrounds me, wildly painted but calm in their expressions; a Canadian person who understands the Potawatomi language is at my side; the baptism is carried out; the savages are praying in their language the prayer of the Lord, the apostolic confession of faith; and the child is named Anthony. St. Anthony is your patron saint and that of several other friends, to whom, as to my loved ones at home, I want to declare in this way my constant remembrance. The child's father's name is "Little Crane"; I will always remember his heartfelt thanks for the admittance of his son into the great association of salvation.(269)

One line in the German missionary's interesting narrative refers to the tree of deliverance in which the baptized sons of the wilderness participate. These words could have been written about the legendary sycamore itself, which would have been but a stone's throw away from the little tree on the hilltop he is describing. In its own way, it has also become a witness to and a symbol of the participation of the sons of the wilderness in the history of Notre Dame's founding over one hundred and fifty years ago.

This venerable old tree, already judged to be the oldest and largest sycamore in St. Joseph County, is more than worthy of homage whether the Indian legend attributed to it is fact or fiction. If the legend draws attention to that fact, it deserves to be associated with the stately old sycamore on the Grotto lawn. Thus far the story holds up very well. Nothing contradicts it being the truth.

One thing is certain. The legendary sycamore is definitely alive and well, as real now as it was on a day in the life of a Black Robe missionary; when Little Crane's son was born and baptized, Anthony, at Ste. Marie des Lacs -- now the University of Notre Dame.

**********

I felt "Providence smiling on my sincere searching" and that campus "God Loop" energy working in the unexpected confirmation of the possible age of the legendary sycamore. It surfaced in a local newspaper article recently, long after I'd about given up ever finding it and just in time to be included as another postscript to this narrative.

The article, which appeared in the South Bend Tribune, featured a picture of Michigan's largest sycamore. I skimmed the article with interest and set it aside to file with my research materials. Its evidential content did not register on me until the next day when something moved me to pick it up and read it again. Whereupon, I discovered that this particular tree had been core-sampled -- a risk that would never be taken with the campus landmark sycamore. Its circumference is 256" and its age has been determined to be 250 to 260 years old. It was the comparison tree I'd been hoping to find and it had almost eluded me. Earlier, I had heard of huge sycamores of comparable size being taken down at the Culver Military Academy but my inquiry came too late, the stumps had been removed without counting the rings to age them.

I compared the measurements and the ring count of the core-sample of this Champion Michigan tree with the one at Notre Dame which is 244" in circumference. Using the formula given me by Purdue, I have calculated that Notre Dame's sycamore could be, as I had earlier thought it might be, from 200 to 240 years old. Using the conservative 200 year figure would mean it was present on campus in the late 1700's. A time when there was much hostility between the early white settlers and the Indians when the Indian legend was said to have taken root. Which means it could have been a fanciful tale, fiction based on fact, or in the category of an "urban" or "rural" legend attached to the tree.

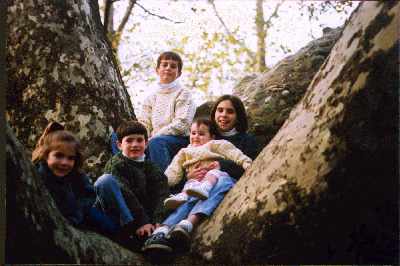

I made a special trip to visit the Michigan tree and it is a massive kingly specimen. However, it is without a place to perch nor is it as friendly and inviting as Notre Dame's Landmark Sycamore which seems to beckon people to lounge in its sheltering arms, as the children of Tish and Patrick Holmes -- Mary Kate, Christopher, Patrick, Kelly, and Kielty -- are doing in this photograph.

In February 1997, in the first Big Trees Contest of St. Joseph County, Notre Dame's Legendary Sycamore -- the oldest tree on campus -- was awarded the title "St. Joseph County's Largest Sycamore". In the summer of 1997, a film company from Chicago spent a whole day filming Notre Dame's Family Tree for a special segment aired during the half-time of the first football game played in the newly opened University of Notre Dame stadium.

Throughout its long life, this majestic sycamore has been immortalized by countless student pictures taken up in it, and in front of it, and published in The Dome from the early part of the century. Recently, the wife of a Notre Dame administrator, Jim Murphy, now retired, told me they had pictures of each of their six children taken in it at various times when they took them to the campus.

In sharing my latest finds with Father George Schidel, who first put me on the path of The Domes, he smiled warmly and excused himself from our conversation. Minutes later he returned, placed in front of me a 1931 copy of The Dome, and opened it to the first identified photograph of the sycamore I have ever seen. Under it were the words Father Cavanaugh had used to describe it -- The Vengeance Tree.

Smiling at my pleased expression, Father Schidel, also produced a photo album of his early days on campus. In it, was another 1931 snapshot of the sycamore. Three students stood in front of the tree and one was standing up in it. When I asked who was in the tree, he grinned and said, "It was me."

As Tom Dooley's cherished letter has been placed at the Notre Dame Grotto, in my mind's eye, I can envision a special stepping stone or bench placed in front of the huge old sycamore so that photographs could more easily be taken up in it. A copy of the legend could then be placed beside it, for all who visit it to reflect upon.

It is comforting to know that in its long life this magnificent Sycamore has seen it all. It has become a witness tree -- a silent sentinel standing guard over the campus and the Grotto -- watching not only the heartaches and the sorrow, but also the joys, of an endless parade of people passing by -- to and from the Grotto. It has endured -- as life endures, generation after generation -- as one of the last of the antique lords of the Indian hunting grounds. More and more I wonder how many years its graceful limbs and lovely foliage have embraced the campus; how many photographs(270) have been taken in front of it; and how many, from little on up, have been cradled in its sturdy branches.

How providential, that two such historic and legendary spots on campus -- The Grotto and The Legendary Sycamore -- share the same scenic lakeside setting. Perhaps it is best that no positive proof of this story ever be found and it remain the legend that it is. If it were proven beyond a shadow of doubt then it would no longer be a legend. It would be history and not nearly as fascinating a tale to tell.