A Cave of Candles / by Dorothy V. Corson

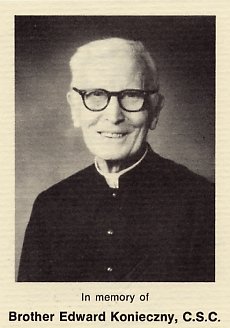

The story that follows was written spontaneously, upon the death of Rev. Sigmund Jankowski, CSC in 1975, as a remembrance and final farewell to our very special Fatherly Friendship. Because it also speaks of my friendship with Brother Edward Konieczny, and he was a very private person, I made a promise to him, when he read it after Fr. Jan’s death, that it would not be shared with anyone else while he was living.

When Brother Edward passed away on August 7, 1984, our story was warmly received at Holy Cross House by those few I shared it who knew or had heard of Fr. Jan and Brother Edward. Father Jan’s spirit lives on in the friendships his memory has forged between myself and his priest and Brother friends still living at Holy Cross House more than thirty years later.

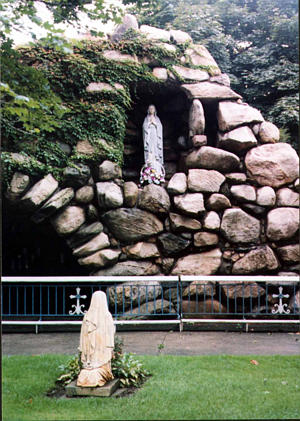

It came as an afterthought, when I placed the story of our meeting, “Always Have a Dream,” in the “The Keystone” Web pages online that perhaps this story of our parting belonged with it. A Cave of Candles: The Story Behind the Notre Dame Grotto would not exist if I had not met Fr. Jan. His part in my researching the story behind the Grotto was a very important piece in the Grotto puzzle which, ultimately, led me to research the Legends and Lore Stories which I have also shared online.

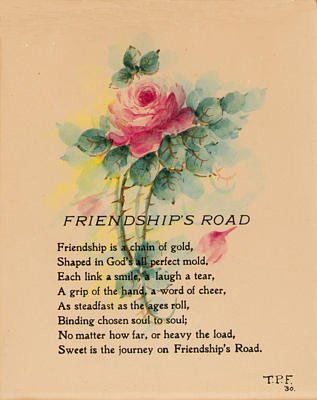

By accident of birth I am not Catholic -- which makes our friendship even more special -- but I have always had a catholic spirit in the sense of having sympathies with all religions. Because of my friendship with Father Jan, in so many ways, that catholic spirit has deepened, allowing me to embrace, even more than I had before, the concepts of all faiths. As Charles Lamb, the poet, has put it: “I bless my stars for a taste so catholic.” For reasons the reader will understand later in this narrative, I have called our story, “Friendship is a Chain of Gold.”

It was dark when we arrived home, Sunday evening, October 5, 1975. We had just returned from a visit with our son, a freshman at Purdue University, a five hour trip there and back. So, it was early to bed after a full and very satisfying weekend.

Early Monday morning, Father Schuneman, Assistant Superior at Holy Cross House on the Notre Dame campus, called to say that Father Jan was slipping fast. After many weeks of far-away-ness, his unseeing eyes blank and his hand unresponsive to the touch of my own, he surprised me a week or so ago, with the last words I ever heard him say. One day while visiting him, searching for some way to comfort him, I decided to say the Rosary for him which Brother Edward had taught me.

Still there was no response from him. As I turned to leave, I placed my hand on his, leaned over near his ear and said, “This is Dottie, Father Jan, remember God loves you.” His hand moved faintly under mine and to my amazement he murmured feebly, “God love you and bless you,” and he added a portion of “My Joy Forever,” which was his endearing term for me. It was so like him and it comforted me to know he was still aware of my visits even though words or a touch didnít seem to register.

I spent most of Monday afternoon by his bedside, his fever running 104 degrees. He was just a whisper of his former self, but he held on with such compliance to what seemed such a slender thread of life. Near the end of the day he appeared to be in a coma. Even so, I had heard their hearing is the last to go and they may know you are there even though it doesnít seem so. The priests and Brothers kept a watch over him when I was not there.

By Tuesday morning he was a little better though his breathing was raspy with the rattle of his lungs laboring. It was a strange sort of day. I had appointments I had no choice but to keep, so I was in and out. I stayed with him for an hour in the morning, left at 11: 25 and returned at 12:45, stayed another hour, and left again to return for a long afternoon. It was 2:45 when I returned -- and God love him -- he waited for me. I decided to let Providence plan my being there if it was meant to be and as always destiny has a way of planning things even better than we can.

He was weaker, still in a coma of sorts. Once his breathing began to falter and I called the nurse, but she said that was usual and he soon returned to his steady labored breathing. After she left I went to him, bathed his face with a damp cloth and moistened his lips with water. I told him I was there, that we all loved him and he was “going home.” When he could still communicate he used to speak longingly of “going home” looking forward to that other world beyond this one. I had said it once before on Monday and he seemed to be trying to form the words with his lips curving them to say “home.” Though he appeared not to be with us, I knew that Monday that he had heard and understood.

Minutes later, I was sitting at his bedside when Father Kane came into his room. I knew his face but I had never spoken to him except in greeting. We fell into a getting acquainted conversation as I thought the sound of voices would be reassuring to Father Jan. Knowing someone was with him, I felt, would be better for him than the silence of someone sitting there in thought.

I kept an eye on Father Jan and an ear tuned to what Father Kane was saying, when I noticed a trickle of colorless fluid run along his cheek. I made a move to reach for a towel to wipe it away when I noticed his breathing falter. It would stop for a second, then haltingly and irregularly return. I rang for the nurse down the hall. As Father Kane and I stepped aside for her, he again stopped breathing. Donna Grounds, the nurse on duty, found he had a pulse. As she turned him from his side to his back, he opened then closed his eyes and fluttered his hand only slightly, as though he were waving good-bye. Quietly and peacefully, like a watch stopping he was gone. It was truly a blessing and I knew in that moment that I was meant to be there, though I did realize at the time what a beautiful ending it would put to our story.

It was my first experience with death. We had kept a vigil, night and day, at my father’s bedside when he was in critical condition after a heart attack. He seemed to be recovering nicely and we relaxed our vigil, only to have him taken suddenly when no one from the family was with him. I had been warned that death was not a pleasant scene to witness, that it would be best to avoid it, but I couldn’t see Father Jan going alone -- as my father had -- if there was any way possible that I could be with him. So I decided to leave it in God’s hands whether I should be the one to be there.

I did not find it anything but what it was, the end of earthly suffering and struggle. A resigned and compliant soul peacefully passing into that other world beyond our comprehension. It was a gorgeous autumn day, one of the most brilliant in my memory, luminous in its breathtaking beauty. I could only think that Father Jan would have been pleased had he known that he left this world on the Feast Day of Our Lady of the Rosary, to whom he dedicated the Grotto, a very special day in his calling. He had spent his life in devotion to Our Lady and even the numeral 7, the day he died, has special religious significance.

I did not find it anything but what it was, the end of earthly suffering and struggle. A resigned and compliant soul peacefully passing into that other world beyond our comprehension. It was a gorgeous autumn day, one of the most brilliant in my memory, luminous in its breathtaking beauty. I could only think that Father Jan would have been pleased had he known that he left this world on the Feast Day of Our Lady of the Rosary, to whom he dedicated the Grotto, a very special day in his calling. He had spent his life in devotion to Our Lady and even the numeral 7, the day he died, has special religious significance.

I was especially touched by a brilliant scarlet leafed tree outside his window and I marveled no more at the beauty of its dying leaves than I did at the soul in sunset ebbing away before me. They say, “Beauty is reality seen through the eyes of love” and so it was for me.

I am all the more convinced that there is no death, only the body dies. I have come to believe that once again Providence had placed me at Father Jan’s bedside -- as we were planted in each other’s lives -- for His purpose. To see that death can be a very beautiful experience, if we want it to be, and not something to fear. I can only say that through it all a warm, ethereal feeling lingers in my heart, too illusive to capture but for a fleeting moment.

I had been through it all, last rites, prayers for the dying, Litany of the Saints, etc. An hour before another priest, Father Switalski, came in to give him communion and last rites as best he could and I was moved by the tears that cascaded down his cheeks and puddled on Father Jan’s pillow. He was so sincere.

After the nurse closed his eyes and smoothed his forehead, Father Kane and I were left to be alone with him. I stood at the foot of his bed, my hand resting on the curve of his toes beneath the blanket, while he too, recited the Litany of the Saints and final prayers over his body. Standing there, I felt his presence still with us, there in that room, until the color began to depart from his face and then I seemed to sense him leaving -- his soul was going and then was gone -- though I knew the spirit that was Father Jan would live on in all our hearts.

At that moment, as if planned, they came to prepare him. Father Kane offered to keep me company while we waited. I had expressed the wish to stay with him until they came for him, something I had not been able to do for my father. When all was ready we returned to his room and waited together.

When the funeral home came, with a parting thank you to Father Kane, I followed Father Jan down in the elevator to the outside door with Brother Roderic keeping me company. We watched together as the hearse sped away. We then exchanged the thoughts that I am sure were occupying both our minds. When our time comes, how quickly all is said and done.

Brother Roderic was to become a dear friend, too. Later on, he became a caretaker of the Grotto. He was the Brother in A Cave of Candles who was given a framed picture of the Grotto by a famous artist who had placed him in the painting.

In the four years I had known Father Jan, the one year he lived at the Fatima Retreat House while we were working on the plaque, and the three years he was at Holy Cross House, the retirement home for priests neither of us had told the story of how we met. Keeping it our secret gave our special friendship a certain glow that telling it might have dimmed. It just seemed the way it was supposed to be, another of those now it can be told stories that had to wait for the right moment.

Just days after the plaque was accomplished at St. Stan’s Grotto Father Jan had a heart attack, he would not be able to return to the Fatima Retreat Mission House. He was transferred to Holy Cross House where he would get nursing care. When he asked me to visit him there, not being Catholic, I told him I really didn’t feel I belonged there. He assured me it would be all right that since being separated from his parish he had very few visitors. “It would please me very much,” he said, “if you’d come and visit me.” Despite my own misgivings, I promised him I would.

It appeared to me, at the time, that most of the priests and Brothers preferred their own company. I rarely saw an outside visitor. Other than the staff or an occasional visiting nun, women were a rarity. From my first day there, I was accepted as family. Because Father Jan wanted me there, my presence was never questioned. Most drew their own conclusions, that I was a niece or a parishioner. To those interested enough to ask, I explained that Father Jan and I were providential friends. Unbeknown to me, while it seemed to satisfy their curiosity, it must have also lent a certain mystique to our friendship that sparked the interest and attention of all those we encountered in the halls and on our wheelchair walks on nearby paths on campus. Most especially, in front of Moreau Seminary, next to Holy Cross House, where I sat under the huge cross facing the lake reading Father Jan’s mail to him.

In the three years I visited him there, only one priest, of a certainty, knew I was not Catholic. He was the oldest priest there at the time, Father Cornelius Hagerty; ninety years old, and a celebrated writer with a sparkling wit that belied his years. With the candid curiosity of the aged, he asked me one day. When I told him I was not Catholic, it only seemed all the more unusual to him. Ever after, whenever he saw us he would shake my hand and kiss my cheek and marvel at what he called “my Christian loyalty and devotion” to my friend, Father Jan.

Soon weekly visits made mine a familiar face. It wasn’t long before detached aloofness melted and I became Dorothy, to faces I didn’t even know, the minute I walked through the door of the sprawling, modern two story-building. But it took awhile for me to sort out the priests from the Brothers and attach names to their faces. Many a charming little story I could tell you of the sparkling conversations I’ve had with priests from far flung countries as far away as South America, Africa and Bengladesh. Many of them were writers and scholars in philosophy, science and religion. Though too numerous to detail here, one story in particular, stands out from the rest because the encounter was so timely.

Brother Edward, who with his friend Brother Cosmos, attended Father Jan when he was still able to say mass very soon attached himself to me, adopting me as Father Jan had done. We were soon exchanging books, poetry and spiritual thoughts. When we first met he introduced me to three books about Mother Seton, which I found fascinating reading. Later, he handed me another book entitled ALL FOR HER. He told me it had been written by a very famous Holy Cross priest, Father Patrick Peyton, the founder of the Catholic Family Hour and the Rosary Crusade which got worldwide recognition, during World War II, for the nonsectarian prayers they inspired. It was his autobiography. The story of an Irish immigrant who became a priest and survived a near fatal disease. When he recovered, he promised to honor Our Lady the rest of his life.

In the center were countless pictures of Father Peyton, a very handsome manly Irishman, surrounded by Hollywood stars, Bing Crosby, Irene Dunne, Loretta Young among them, drawing huge crowds wherever he went. I was very impressed with the book and this man’s spiritual dedication and decided one day to read it to Father Jan. We were downstairs in the parlor. I had reached the part about his early life in Ireland, when the parlor began to seem too chilly for Father Jan. I was guiding his wheelchair through the double doors when a man I didn’t recognize, asked if he could be of any help. Although he was dressed casually, I assumed he was a priest or brother new to the house, and not accustomed to seeing a woman there, thought I might not know my way around.

He approached the other side of Father Jan’s wheelchair as I explained why we were leaving. “A very interesting book,” I told him, as I held it up for him to see the cover. It’s about an Irishman who wanted to become a millionaire and instead became a priest. He nodded his head and smiled as I continued. “I guess he was as stubborn as a mule when he was a young man and got into a lot of scrapes, being he had an Irish temper to go with it.” He chuckled at my comment. I thought he was politely agreeing and knew of the book when he said, “That he was.” About to part company it occurred to me that I hadn’t introduced myself. I told him my name and asked, “Are you a priest or a Brother?” “Father Tom,” he said. When I asked his last name, a surprised look came over his face, he must have thought I knew. He laughed and said, “I’m Father Tom Peyton, the book you’re reading was written by my brother. The early part of the book is about the two of us when we came from Ireland.” He told me they had become priests together and he pointed out himself in the pictures of the family in the center of the book.

We both had a good laugh at the coincidence of our meeting and it wasn’t long before it was a good story that had made the rounds. Father Peyton and I had warm talks whenever we chanced to meet after that as he filled me in on his brother whose activities at the time were based in Tunisia in North Africa.

In spite of all the warmth and friendliness I had experienced at Holy Cross House, once I was faced with the prospect of unfamiliar funeral services, I wasn’t sure what I should do. All I knew for certain was that I would be waiting at the cemetery when the services were over.

Well, I thought, I’ve been led this far, surely I’ll get a nudge that will tell me where I am to go from here. It was Brother Edward’s friendly persuasion that decided it for me. He called that night asking me to attend a Mass with him at 5:00 pm at the seminary. He then invited me and my husband for dinner at Holy Cross House at 6:00 pm and the wake service at Moreau Seminary at 7:30 pm, when Father Jan would be on view.

I hesitated, my timidity overcoming me. Never having been to a Catholic Mass before, nor inside a church for more than 13 years, I was a little afraid the roof might fall in on us. And I wondered if Brother Edward knew I wasn’t Catholic. He caught my hesitation, and anxiously went on, “I know Father Jan would want you to be there,” he said, “and all the Fathers and Brothers too. It would please me very much if you would be my guest.”

With such a gracious invitation, how could I refuse. Somehow, it seemed the way it was supposed to be. I told him I’d be honored to attend the service with him. And so began the climax of one of the most extraordinary experiences of my life.

That evening I was drawn to my typewriter moved to record my impressions as they happened. I left my typewriter at 10:00 pm, read the newspaper and a chapter of a book I was reading, and went to bed. At 5:00 am the next day, I awoke from a sound sleep, got up for a glass of water and returned to bed. Lying there, by then, in no mood to sleep, I thought of Brother Edward meditating over a cup of coffee or being joined by one of the night nurses. His day was just beginning. I had only just learned that his day began at 4:30 or 5:00 am each morning and ended at 10:00 pm, with time out for meals, an hours nap after lunch, and a hour break between serving Mass for the ailing priests. Though he has had this schedule for ten years, and he himself is facing cataract surgery, I have never seen him without a beaming smile and a glad hand for everyone. A truly gentle man, always cheerful, and so happy to be busy in the service of his Lord; so dedicated to his vow of poverty that he keeps no material possessions. His treasures are books, inspirational articles and favorite poems he has collected over the years.

That evening I was drawn to my typewriter moved to record my impressions as they happened. I left my typewriter at 10:00 pm, read the newspaper and a chapter of a book I was reading, and went to bed. At 5:00 am the next day, I awoke from a sound sleep, got up for a glass of water and returned to bed. Lying there, by then, in no mood to sleep, I thought of Brother Edward meditating over a cup of coffee or being joined by one of the night nurses. His day was just beginning. I had only just learned that his day began at 4:30 or 5:00 am each morning and ended at 10:00 pm, with time out for meals, an hours nap after lunch, and a hour break between serving Mass for the ailing priests. Though he has had this schedule for ten years, and he himself is facing cataract surgery, I have never seen him without a beaming smile and a glad hand for everyone. A truly gentle man, always cheerful, and so happy to be busy in the service of his Lord; so dedicated to his vow of poverty that he keeps no material possessions. His treasures are books, inspirational articles and favorite poems he has collected over the years.

As I lay there, words spinning around in my brain, I knew that sleep was out of the question. The thoughts in my head were forming sentences luring me back to my typewriter. I reached for my clothes, closed the bedroom door quietly behind me and stole up to my attic sanctuary. I knew I wouldn’t rest easily until what was in my head was down on paper.

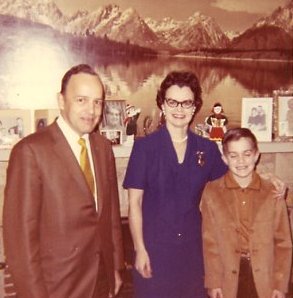

Later in the day, with a flutter of the senses and the heightened awareness that precedes what the heart recognizes, intuitively, will become one of life’s memorable moments, I prepared to meet Brother Edward for the 5:00 o’clock Mass. I had already made arrangements with my husband to meet us for dinner in the Holy Cross dining room when he left his office for the day.

What should I wear? Again, instinctively, I picked a dress, years old, which from remarks made of it, turned out to be the perfect choice for the occasion: a soft royal blue knit suit dress, a rich glowing color that is a favorite of mine. Brother Edward called it, “heavenly blue -- the color of Mary’s mantle” and he added that the beauty of that dress would always mark the occasion for him. He even noticed the tiny, gleaming mother-of-pearl cross I had added to the string of pearls around my neck. I was to learn that Brother Edward found beauty in everything that touched his life, from nature’s tiniest autumn leaf to the smallest gesture of kindness. Somehow, miraculously, he had retained that childlike wonder and delight in living. An enthusiastic quality of life that illuminates the commonplace.

What should I wear? Again, instinctively, I picked a dress, years old, which from remarks made of it, turned out to be the perfect choice for the occasion: a soft royal blue knit suit dress, a rich glowing color that is a favorite of mine. Brother Edward called it, “heavenly blue -- the color of Mary’s mantle” and he added that the beauty of that dress would always mark the occasion for him. He even noticed the tiny, gleaming mother-of-pearl cross I had added to the string of pearls around my neck. I was to learn that Brother Edward found beauty in everything that touched his life, from nature’s tiniest autumn leaf to the smallest gesture of kindness. Somehow, miraculously, he had retained that childlike wonder and delight in living. An enthusiastic quality of life that illuminates the commonplace.

As I headed for the 2nd floor nurses station -- a glassed-in semi-circle with halls radiating from it -- I caught a glimpse of Jeanine, one of the night nurses, attending a patient. I paused in the doorway to say good-bye, expecting this might be my last visit. “Dorothy,” she said in greeting, “you were Father Jan’s dearest friend, thank you for your kindnesses to him.” Warmed by her comments, in Father Jan’s behalf, I thanked her for hers. All the more aware, that a dedicated nurse, one who relates to her patients and is good at her job, is truly “an angel of mercy” to the weak, the weary, and the sick-at-heart. There must be a very special place in heaven for geriatric nurses and aides for it is a special calling and one to which very few are suited.

Within minutes, Brother Edward joined me, having changed into his habit. We proceeded to the main floor and out the rear door where a paved path led along the lake to the Moreau Seminary next door. Father Craddick and Brother James, who were chatting at the end of the rear ramp, turned to us as we approached and remarked to me: “We were just talking about you. When you were visiting Father Jan yesterday, we overheard one of the priests saying; ‘Here comes good old reliable.’” In the past four years, I had never missed a weekly, and sometimes twice weekly visit when Father Jan was in the hospital. We all chuckled over the comment. Then as we turned to leave, Father Craddick told me the combination to the always locked doors at the seminary. “Just in case Brother has trouble with it,” he said, referring to Brother Edward’s eye problem.

I walked into the Moreau Seminary chapel for the first time, to attend my first Mass, almost the only woman in a crowd of seminarians. It was a beautiful ceremony with a guitar trio leading the singing. I was surprised to find myself very much at ease as Brother Edward turned to me and whispered: “In a minute the young man beside you will turn and say, ‘the peace of Christ be with you,’ and then you reply, ‘and with you also,’ it’s customary.” I found it a very friendly get-acquainted gesture that made me feel right at home. No unusual actions occurred to set me apart, the procedure not unlike our own. If Brother Edward knew I was not Catholic, and I am sure now he was one of the few who did -- bless him -- he never let on, which put me right at ease.

My husband was waiting in the parlor when we returned to Holy Cross House and almost immediately we went into the tastefully appointed dining room. It was ringed with circular tables each seating six, a buffet table and a salad and soup bar. I had passed it many times during my weekly visits, noting its homelike, cozy atmosphere, but I never in the world thought I’d be the only woman there in a room filled with black robed priests and Brothers.

Surprisingly, the “fish out of water feeling” left very quickly when another priest I knew made a fourth at our table welcoming us with friendly conversation. As the meal progressed, in rapid succession, many priests and Brothers stopped at our table to welcome us, tell an Irish joke and exchange bits of conversation. It was only the beginning of a feeling of fellowship that permeated what was to become a unique and memorable evening in my life.

My husband, who has never known a stranger, amiably chatted with a group of priests until it was time for the wake service to begin. As we again set out on the path to Moreau, Father Peyton took my arm with warm-hearted Irish chatter. My husband and Brother Edward following behind us, the rest of the group trailing them.

Pausing at the door to wait for the rest of the group, Father Peyton made a move to knock on the window to alert someone to unlock the door. At the same time, I pushed the buttons on the combination lock, turned to Father Peyton with a mischievous grin, and opened the door. His bighearted Irish voice boomed out in laughter as the others approached. “Shure and begorra,” he exclaimed, “she knows the combination to the seminary and half the priests don’t.” Good-humored laughter rang out in unison and I got kidded the rest of the evening when we left again through that same door.

Once again, I entered the chapel this time for the wake service. As I viewed Father Jan, I was consumed with the mixed emotions that undoubtedly flood any feeling person’s mind at the sight of that still wax replica of a once pulsing human being. This was not the Father Jan I knew, this shadow of the man, and there was comfort in being able to feel impersonally about it. Standing there, gazing pensively at his still form, it came to me with quiet conviction, that like my father, he had stepped out of his physical body. Truly, it was just a shell -- an imprisoning cocoon -- he had cast aside as a worn out garment. And like a butterfly, his spirit was soaring heavenward.

I could not be unhappy for him. Inwardly, I felt joyously elated for him. Being there, having shared his last moments on earth -- and that seemed planned too -- I could only feel myself filled with a quietly calming assurance that his soul was unhampered now by a mortal being whose weariness had become almost too great a burden for him to bear.

So, it was not sadness I felt as I gazed at him, but more a slowly unwinding, illuminating enlightenment, a piercing, bright beacon in my mind probing the inexplicable darkness and perplexities of death in my first close encounter with it.

I was mindful of my placid objectivity, yet not altogether surprised at myself. In the past, I had found my nature to be calm to the core in the most dire and distressful situations, while I could be moved to tear in an instant at something touching or beautiful.

I am sure my greatest consolation, the thought of which to a great measure contributed to my ease of mind, was the remembrance that Father Jan and I had said our good-byes more than two years before, when he was still himself, but in a gravely weakened condition. He had been anointed and prepared for death for it was thought that he would not last through the night. I had told him that if he ever wanted to see me, day or night, to have someone call and I would come. And so it was that nearing midnight, I received a call from Sally, a night nurse at the time. She explained that Father Jan had asked for me, there wasn’t much hope for him, and if I wanted to come -- the doors were locked for the night -- to ring the night bell and she would have someone alerted to see me in.

My husband and I arrived shortly afterward. I stood by his bed for over an hour holding the hand with which he gripped mine so tightly. It was as if he were draining consolation from the comfort of a familiar name and face he’d grown fond of. They say a friend is someone who walks in when the rest of the world walks out. Perhaps I had become that friend to Father Jan when he was separated from the church and parish he had lived his life for.

“I wanted you to be able to see him,” Sally said, “but there will be no need for you to stay with him, sleep will be the best thing for him. I’ve ordered I-Vs from the hospital, something we donít usually do, so it will be necessary for a nurse to be with him.” Sally, a single woman, had already gone off duty, but dear heart, she had taken it upon herself to stay. To watch over his care and see him through the night. I had kissed his sleepy cheek and bid him good night, not knowing if I would ever see him alive again. He roused himself and mumbled, “You are my joy forever, God bless you, Dottie.” And I answered my usual: “He already has, Father Jan, sleep well.”

He surprised everyone by making it through the night, but spent many days in the hospital afterwards. He never really recovered his spirit or his strength after that night but kept going steadily down hill. From walker, to wheelchair, to bed, his eyes rapidly dimming to blindness. I guided his hand as he lovingly inscribed one of his books, When Dreams Come True, to Sally, the nurse who watched him through the night. It became the last one he ever autographed. For me, the Father Jan I knew -- the spirit of the man -- died that night, while the soul and body held on, seemingly waiting, for the last threads of the tapestry of his life to be woven.

To stifle Father Jan’s boundless energies and tireless, aspiring nature was like trying to stem a rising tide. Going to Holy Cross House was like being put to pasture when his mind told him he had a lot of miles in him yet, and so many things he wanted to do for Our Lady. In the beginning, he struggled, naturally and humanly, against the frustrations of being confined. He had a fervor and passion about him, a strength of purpose, that made him a man who could accomplish most anything he set out to do. He was like the man who knows where he’s going, the world has a way of stepping aside for him. And Father Jan, I understand, had this way about him. He expected a lot from others, but he expected even more from himself.

Having known him only a short time, I only caught a glimpse of this lion-hearted side of Father Jan. I saw it mainly in his dedication to his priesthood and his devotion to Our Lady. To me, under a stern and strict exterior, he hid a heart as downy soft as a kitten, and just as irresistible to anyone who really knew him. He had a way about him all his own, a sensitivity to people and their problems. He knew all his nurses names, knew their joys and their sorrows. He really cared about people from little on up and thrived on meeting their needs. It was this same sensitivity of feeling that made him suffer so acutely the loneliness and anguish of inactivity that cut him off from the parish he had grown to love as his family for 22 years. One line under his 1922 graduation picture in THE DOME yearbook says it all, “‘Jan’ has simply smiled his way into the hearts of his associates. ‘If you want to be smiled at, smile,’ said he.”

Father Jan was always first to admit his failings, and impatience, he said, was one of them. Seeing the change in him after that last close call, I asked him one day, “Father Jan, have you given up, or have you resigned yourself to your situation?” “I’m resigned,” he said, “It’s God’s will, he had to humble my impatience and my pride.”

Now and then he would make a brief telephone call to me, from the nurses station, just to say hello and hear my voice. In his wheelchair, he could not dial my number from the common wall telephone as he had done before. Soon after, room telephones were installed so the nurses station telephone would not be tied up. The only way out with a wheelchair, was through a sliding glass patio door. It was quite a feat getting the wheels over the aluminum track. Weeks later, to my surprise, a sloped cement wheelchair ramp was put adjacent to the steps leading out the main back door.

I reminded him of the changes for the better I had witnessed recently in his surroundings. The room telephones, a special comfort to Father Jan to keep in touch, a ramp for his wheelchair walks, more visitors from outside the order. I told him it only served to point out how purposeful his infirmities had been. How much God had used it to improve the lot of others who would come after him.

“Do you remember this from THE IMITATION OF CHRIST,” I asked him. “Whence shall thy patience be crowned if thou meet with no adversity?” He smiled, knowingly, and asked me to read it all to him.

There would be times when the past was crystal clear, but the present foggy, then bit by bit over the last months even his mind began to fail him. The months stretched into a year, then two years, this summer there would be no wheelchair walks.

Through it all, I waited with him -- as I never had the chance to do with my own father. I waited and wondered. I wanted to go on believing that there was a purpose in every problem and a design in every difficulty. So in my mind, I was always searching for reasons why he should go on lingering, seemingly so purposely. Those reasons I was only now beginning to discover . . .

Standing there, gazing at Father Jan in his coffin -- though I wasn’t aware of it then -- the pieces of the puzzlement were being sorted out in my mind and deftly put together. As I turned to leave, the last thing my eyes caught in remembrance was the beautiful cocoa bead rosary clasped in his hands; a gift given to him by the Ladies Rosary Society when he had to retire as pastor of St. Stan’s after brain surgery. The nun who was the nurse in charge at Holy Cross House when Father first came there so admired it that she feared it might get lost in his room. She asked me if I would keep it safe for him, “until he asks for it or it is needed.” I had never seen Father Jan without one. This very special one I’d kept in safekeeping for him in a corner of my jewelry box these past several years was a little bit of me going with him.

Now we were sitting, my husband and I, flanked on both sides by priests and Brothers, feeling very much a part of the fellowship of their company. The wake service was lovely, as expected, but it was the eulogy that drew my avid attention. His lifetime devotion to Our Lady was stressed, and so many accomplishments in her honor mentioned I’d never heard about, that I marveled anew at the practicality and dedication of his efforts in her name.

It was noted that he died on the Feast Day of Our Lady of the Rosary, October 7. The St. Stan’s Grotto, dedicated to her, was mentioned as his crowning achievement in her name. I was warmly surprised hearing my father’s name mentioned as the master stone mason who built it. All the more so, because I knew the priest giving the eulogy, Father Hosinski, the current pastor of St. Stan’s, did not know me and could not have known I would be there. It was an unexpected, sweet surprise, and a warm remembrance of my own father.

As we were about to leave Moreau, Brother Edward, who of late had been learning to say Peace in all different languages, reminded me that he wanted me to meet a Professor Carter. He was a language expert from Portugal, an ex-submarine commander, and now teacher of the seminarians. “A brilliant man,” he said, “one of the best, you must meet him.”

We were surrounded by a cloud of black robes, being introduced to priests and Brothers I had not yet met from other parts of the campus, while a seminarian was sent to find Professor Carter.

Expecting to see a sober and serious professor, I came face to face with a broad, beautiful smile that exuded friendliness, and eyes that sparked with the kind of interest that stems from boundless enthusiasm. As we were introduced, to my astonishment, for I had never seen him before in my life, he said to my husband: “Your wife has set a beautiful and touching example of loyalty and devotion to a friend.” Nonplused, I said, “but I donít know you.”

Expecting to see a sober and serious professor, I came face to face with a broad, beautiful smile that exuded friendliness, and eyes that sparked with the kind of interest that stems from boundless enthusiasm. As we were introduced, to my astonishment, for I had never seen him before in my life, he said to my husband: “Your wife has set a beautiful and touching example of loyalty and devotion to a friend.” Nonplused, I said, “but I donít know you.”

With a mischievous glint in his eyes he went on: “But I know you,” he said. “Over the years, I’ve watched you from my window, wheel your friend down the path and stop under the cross to read his mail.”

I recall sitting there with Father Jan, gazing at the beauty of the stained glass windows in the chapel, but I never in the world thought I’d ever be viewing them from the inside. And I remembered thinking how deserted Moreau looked. Only now and then a student or priest would stop to chat with us on their way to other buildings.

In amazed response, I laughed too, coloring a bit, I’m sure, with warmth and pleasure, as I answered: “Well I guess that only goes to show you never know who may be watching when you least expect it.” It was such an unexpected and sincere compliment that I felt I could live on the glow of it for months. To think this brilliant and busy man would have even noticed us, and remembered it, when we hadn’t been on that path for over a year. How interesting that we should meet and in such an unusual way, through Brother Edward. Or was it Providence again?

The day had been sunny and bright, and warmly comfortable, very much like the day Father Jan died. The evening, now, as we left Moreau Seminary after the wake, was balmy. A caressing breeze marked the night apart for me. I knew I would never forget it. In the same way I would never forget the first time I saw the St. Stan’s Grotto or the one at Notre Dame. There is an indelible impression etched in my memory of a cave of candles and a blissful balmy night. I found myself measuring the moments, wanting to remember it all in abstract detail. I was with it, and yet set apart from it, viewing it objectively and recording it in my memory.

When we returned to Holy Cross House, we separated from the others, continuing on with Brother Edward. He had told me that he had been given permission to set aside a remembrance for me from Father Jan and he was anxious for me to have it. I told him I didnít need a remembrance that I had my memories, but he so wanted me to have it, that I couldn’t refuse him. “It’s perfect for you,” he said.

|

FRIENDSHIPíS ROAD T.P.F. |

Once again we were in the upper corridor in a small hallway of alters where infirm priests were assisted in saying mass. Brother Edward reached into one of the many drawered cabinets and placed in my hand a small antique framed poem entitled, “FRIENDSHIP’S ROAD,” which belonged to Father Jan. It was inscribed over an original sketch of a fragile pink rose. So warmly pleased that it was, indeed, the perfect remembrance of our friendship, I was about to express my pleasure in it when he placed in my other hand a delicate blue crystal rosary, dim with age, and what looked like a fountain pen. Engraved on the back of the crucifix, which later cleaned up beautifully, was the word Italy, undoubtedly from his European trip to the Holy City. The fountain pen, he told me, was a special one for priests in which to carry holy water for emergencies and he pointed to the Pax symbol on the cap.

As he handed them to me, he added, “I know Father Jan would want you to think of these as remembrances from him -- one for the mind, one for the heart, and one for the spirit,” and he beamed with genuine pleasure at being the one to pass them on to me.

Brother Edward placed them in a manila envelope and I tucked them under my arm as we prepared to leave. Then, with what I had come to recognize as one of Brother Edward’s many flashes of inspiration, he suggested a last cup of coffee in their snack bar. We hesitated, not sure we should prolong a most satisfying evening. But, seeing the eagerness in Brother Edward’s eyes, we were so glad that we did, for it turned into a warm and stimulating rap session with the several Brothers who joined us.

As we gathered around the table, I looked up at Brother Edward and at that very same moment, he looked up at me with a look that seemed to say: “You have sparkled my day.” With his snow white hair gleaming in the overhead light and a glitter in his eyes that spoke of pleased satisfaction -- like the cat that swallowed the canary -- he said with a chuckle and a sigh: “You came . . . I was so afraid you wouldn’t.”

As he spoke his face was washed with pleasure. I felt the walls of his friendly, yet always polite reserve -- and my own too -- come tumbling down. I knew in that moment how much he wanted this to happen. How important it had become to him that I should not just fade out of the picture. I could see him relax his fervor, the weight of the concern he felt that I might not return fell away from his tall, lean shoulders. I was a part of his family now. He knew it, and he knew I knew it, which I’m sure was his heartfelt intention. He also knew, my being me, I would not and could not, turn my back where there was still a need Providence had given me the resources to meet.

One of the Brothers at the table, a younger man who lived at Moreau, I had met on the day Father Jan died. He mentioned then that he worked with the terminally ill at St. Joseph Hospital in South Bend. He drew me aside as my husband and I were rinsing out our coffee cups in the galley kitchen, as we prepared to follow Brother Edward who was several paces ahead of us waiting in the hallway.

“You know,” he said, very much in earnest, “You have something very special here. I’ve never seen these men accept anyone as they’ve accepted you. They have a cool detachment born of habit that keeps even the young seminarians at arm’s length. It’s very gratifying to see someone who can break through that reserve. Had you thought of what a wonderful apostolate that would be? They need your kind of warmth.” Not having heard the word before, I wasn’t sure what he meant. And I wondered what he’d think, if he knew I wasn’t Catholic nor even a true Protestant. I thanked him and began to ponder what he’d said as we joined Brother Edward in the hall and prepared to leave for home.

Then I conceded in my mind that perhaps that was the very reason. I did not have the prejudice of the true Protestant, nor the awe of their position as priests of the Catholics. I was just myself and that allowed them to be themselves in my company. I was not impressed with their importance as priests but more with the fact that these were extremely learned men, now lost to the world. They were important to me because they were human beings. Highly educated men, yet lonely and forgotten now, by the outside world because they had chosen to forego having their own families in order to spend their lives on all people.

Spending a lifetime on learning, many were brilliant in their fields, so it was their fertile minds that fascinated me and perhaps they caught that genuine interest I felt in learning of their backgrounds and their special interests. Perhaps because I did not see them as priests, but as fellow human beings, they did not have to be a priest with me. They could be individuals with varied tastes and talents.

The role of a priest has to carry a lot of weight. It would be understandable that shedding it, if only for a little while in conversation, would be a comfort. It would seem that the image must be kept, even among themselves. Wouldn’t that be what was expected of them?

Then along came a stranger -- a younger woman to them -- and isn’t it said that the easiest person to get to know, is a stranger? Or perhaps, it was Father Jan’s undisguised humanness, his need for warmth, friendly conversation, and companionship from someone outside their order, that unmasked their own needs.

So often, when we strike up a conversation with a friendly stranger, our guards are down. We reveal more of our true self because this stranger has no preconceived ideas about us. We become as two people from the “other side” talking things over. And a priest is a man like any other. The English call it “yarning,” young people call it “rapping,” and I call it the warmth and friendship of good old fashioned coffee and conversation. As human beings, we all need it!

As we were leaving Holy Cross House that evening, I told Brother Edward that, as it stood, I did not plan to attend the funeral service the next day at St. Stan’s, but I’d see him at the cemetery as I knew he would be involved with the large group of priests taking part in the ceremony.

As we were leaving Holy Cross House that evening, I told Brother Edward that, as it stood, I did not plan to attend the funeral service the next day at St. Stan’s, but I’d see him at the cemetery as I knew he would be involved with the large group of priests taking part in the ceremony.

The artist friend who had introduced me to Father Jan had called the day before to tell me she felt honored to be asked to sing in the choir even though she was no longer a parishioner. She mentioned my coming and although surprised to learn I would not be there, she seemed to understand, when I told her I had gone to the wake service but I was a little uneasy about attending the funeral service. I explained that I was not familiar with St. Stan’s church, his relatives, or the parishioners, and felt perhaps I did not belong there. “Unless something unforeseen happens,” I told her, “I will not be there, but I will see you at the cemetery.”

When I mentioned my misgivings to my husband, he told me he too felt I’d paid ample respect to Father Jan at the wake service, but assured me that should I change my mind, knowing my shy nature, he would leave the bank and accompany me.

In the two days between Father Jan’s death and the services, I found myself notifying people I thought might want to know about him by letter. Especially his adopted sister, Sister Bertha, who was a nun in California. It was Sister Bertha who referred to Holy Cross House as “The Vestibule of Heaven” something I had never heard before or since. I had already decided that when the time came, I would present Father Jan’s copy of our story, “Always Have a Dream” -- the one I wrote in 1972 to commemorate our placing a plaque at the St. Stan’s Grotto -- to Holy Cross House. I was busy getting it in order, adding a postscript tribute to him, and writing thank you notes to those who had been especially kind to Father Jan, so I could drop it off at Holy Cross House after leaving the cemetery.

Having put a lot of myself into the past few days, I awoke the day of the funeral service intent upon catching up on any housework I’d put aside. I was leisurely going about my work when a little voice, surprisingly like Brother Edward’s, whispered in my ear, “Father Jan would want you to be there, Father Jan would want you to be there.”

It was nearing 10 o’clock and the service was at 11 o’clock across town. I knew I had to decide quickly if I was to be ready in time. My husband would also need time to make preparations to leave his office and pick me up. It seemed like too much of a rush, but that little voice kept persisting until I suddenly recognized it as that “green light,” the reassurance that I belonged there after all.

Indeed, everything was so right, and such a perfect and beautiful ending to our story, that I knew it was meant to be. And like the evening before, I could not have stayed away if I had wanted to. Some irresistible inner force was plotting the course -- willing me to be there.

I dressed hurriedly, automatically choosing the same soft blue suit dress I had worn the night before. I added only a triangular shaped head scarf of black Spanish lace from Madrid, a long ago gift left untouched in my drawer for years. Saved for this occasion . . . I wondered?

We made it as if it was planned to the minute. Seeing Brother Edward coming down the walk with a group of priests, we waited for him at the church door. His pleased grin widened into a happy smile as he approached us. “Father Craddick spotted your heavenly blue dress right away,” he said. He joined us in the last row on the aisle while the priests went in to change. It was an impressive sight to my inexperienced eyes to see, within minutes, the area Catholic Bishop followed in pairs by a large number of priests, richly robed, all Father Jan’s friends.

It was a very long funeral procession, the longest I had ever been in. As it wound its way back to the St. Mary’s entrance to the Notre Dame campus a swirling cloud of brilliantly colored autumn leaves were falling like rain. They settled in clumps among the simple crosses that marked the community cemetery in a woodsy glade in the uppermost part of the campus. After a short graveside service, my husband took my hand and we walked slowly back to our car as we heard in the distance the impromptu voices of the Ladies Rosary Society singing Father Jan’s favorite hymn.

Hoping to get away quickly, as almost two hours had passed since my husband left his office, we found instead that we had to wait as other cars had ours hemmed in. In the interim, it crossed my mind to pick up several brightly colored leaves, to press, and add to the pages of the “Always Have a Dream” booklet, about the plaque at the St. Stan’s Grotto. A fitting addition, I thought, and that too seemed to be another planned reason for our delay in leaving.

I had promised to return to Holy Cross House after the service, so I had a quick lunch with my husband and dropped him off at his office. Then I returned home, changed quickly, picked up the booklet and returned to the campus. I planned to leave it at the nurses station for anyone who was interested to read, this being the first time they would know the story behind our friendship. I also planned to tell them that Iíd be back, in Father Jan’s memory, on November 7th the monthly anniversary of his passing.

“The light green grass in this painting of Holy Cross House represents the good works of those who have entered this vestibule. The green grass depicts life and hope. The single golden leaf floating down from the tree represents all the priests and Brothers who have gone to their reward in Heaven. Like the leaf, they have returned to the earth from which they came. They gave their lives to bring forth the new growth of their good works -- the green grass. Look closely and you will see that the sidewalks form a Cross. The Cross leads to the Community Cemetery -- their final golden resting place.” Robert F. Ringel

Now, viewing all this in retrospect as I write this, knowing the universal response that followed their reading our story “Always Have a Dream” -- the warm phone calls and notes I received -- I am all the more convinced that deep within every person is a sleeping spirituality. A hunger, buried deeper in some than in others, to express their own innermost thoughts. And perhaps, being unable to, they recognized themselves and their fellow feelings in the sentiments I tried to express in my tribute to Father Jan.

Emerson said it best:

In silence, in steadiness, in severe abstraction, let him hold by himself; add observation to observation, patient of neglect, patient of reproach; and bide his own time,--happy enough if he can satisfy himself alone, that this day he has seen something truly. Success treads on every right step. For the instinct is sure that prompts him to tell his brother what he thinks. He then learns that in going down into the secrets of his own mind he has descended into the secrets of all minds. He learns that he who has mastered any law in his private thoughts is master to that extent of all men whose language he speaks, and of all into whose language his own can be translated. The poet, in utter solitude remembering his spontaneous thoughts and recording them, is found to have recorded that which men in crowded cities find true for them also. The orator distrusts at first the fitness of his frank confessions,--his want of knowledge of the person he addresses,--until he finds that he is the complement of his hearer; that they drink his words because he fulfils for them their own nature; the deeper he dives into his privatest, secretest presentiment, to his wonder he finds this is the most acceptable, most public, and universally true. The people delight in it; the better part of every man feels, This is my music; this is myself.

"The American Scholar" in Essays and English Traits (New York: P.F. Collier, 1909).

Knowing this, and the non-inferential way it came to me, I thanked each one for their kind thoughts, giving God the glory, for no one knew better than I did, that the inspiration had come from outside myself. I could not claim any credit for it and I assured them the praise would not go to my head, but to my heart, where the inspiration for the story and the poems had come from.

The most startling disclosure of all came from quiet, reserved, Brother Edward. After reading my story, he completely opened his heart to me: “Now I know why I was drawn to you from the very first. There was something magnetic about you, but I never really knew you, inside, until I read your story.” Brother Edward, so lovable and irresistible himself, I am finding to be one of the most spiritual and saintly men I have ever known. Though frail in appearance, his tall, slim form hides a mind like a steel trap, filled with reams of Latin phrases he has already begun to teach me. The poetry and books he has shared with me fit right into my searchings. He exudes a wittiness and warmth that is uplifting and inspiring with a sweet innocence and purity of heart and soul that astounds me. He is forever sharing me with anyone at Holy Cross House he thinks needs company, then he mysteriously disappears out of sight.

Once again, I cannot help but feel that I am being led, as I was led so providentially to Father Jan; that this might very well have been God’s plan in Father Jan’s lingering illness. A link, that was Brother Edward, was being forged to keep me from leaving. Certainly, I had not chosen an apostolate . . . but perhaps it had chosen me. And if so, the question was where it was leading me this time and whether I would have the inner resources to meet it.

Dorothy V. Corson

October 7, 1975

|

Life . . . Is measured by time; The soul . . . By the depth of our experiences.

|

I know all this now, as I am writing this, [October 17, 1975] but I didn’t know it then. When I left our story at the nurses station at Holy Cross House. I paused to chat with those I encountered in the hallway on my way out and wondered to myself . . . will they still feel the same when they know I’m not Catholic?

Father Melody, Superior of Holy Cross House, stepped out of his office as I was leaving to thank me for coming and we exchanged comments on how impressive the service was. He told me, as many others had, to come back soon, not to be a stranger.

I let him know I planned to return in a month. I wanted to give them all time to absorb our story and decide if they still wanted me there. And I added that as long as Father Jan lived in me, I’d be back, because he wouldn’t want me to forget his friends. His Irish eyes beamed in appreciation and he gave me a warm, friendly smile as I turned to go, but I knew I had to leave it in God’s hands whether that same warmth would be there when I returned . . . .

Whatever, I knew no one could rob me of the glow of this inspirited, illuminating interlude in my life. Perhaps it really isn’t the deed, but what the deed does to the doer -- that counts. I only knew that I would tuck that warm, glowing feeling away in my heart and bring it out on rainy days to relive the warmth and wonder of it.

Driving back to St. Stan’s as I had planned to do, to arrange for candles to be lit at the Grotto, I tasted the deliciousness of another golden day associated with Father Jan. I was absorbing the feel of it and imprinting it on my mind so that in all my life I would never forget it, the trees raining color, breezes caressing the most delicate senses and the fragrance of leaf burning in the autumn air.

Returning to the campus to do the same at the Notre Dame Grotto, it seemed too nice a day to keep to myself. I felt I must share the memory with someone else, someone special. I decided to pick up my niece, Kelly, who was almost six, the same age our son was when we did the same thing eleven years before, after his grandfather’s death. She, as his youngest grandchild would light the candles, one for the grandfather she never knew, and one for Father Jan.

She was delighted and intrigued by it, and just as serious as Greg was in her selection of just the right place to put them. Then, depositing money in the container, we walked across the lane to the lake to see the ducks, her eyes sparkling with interest. One day I had driven Father Jan to her home, a mile from Notre Dame, so he could give them some of his quail for their woods, but she was too little at the time to remember him.

She was delighted and intrigued by it, and just as serious as Greg was in her selection of just the right place to put them. Then, depositing money in the container, we walked across the lane to the lake to see the ducks, her eyes sparkling with interest. One day I had driven Father Jan to her home, a mile from Notre Dame, so he could give them some of his quail for their woods, but she was too little at the time to remember him.

“What happened to Father Jan,” she pleaded, “Where is he.” “Well Kelli,” I told her, “he must be in heaven now, where we will all go someday. But even if he doesn’t live here anymore, except in our hearts, a place has been marked on earth so you will always remember him. Would you like to see it?” “Oh, yes,” she exclaimed.

So, we followed the winding road to the clearing in the woods where the white crosses marched in neat rows across the green grass. She danced along the path asking me to read the names. “So many Brothers,” she said, a bit perplexed, “but where are all the Sisters?” I explained that they had a very special place all their own.

As we neared Father Jan’s freshly seeded grave, we sat down on the grass and rested awhile. I asked her if she would like to pick one of the colorful leaves, to press, to remember the day by. “It will be like a snapshot from a vacation trip,” I told her. “When you see that pretty leaf you will be reminded of the day we lit candles for Grandpa and Father Jan and you will feel all warm and glowy inside remembering it.”

With her other hand, she reached for mine as we left, her little mind taking in what I had said. Then, suddenly, she stopped after we had gone only a few paces, looked at me searchingly and said: “Aunt Dottie, Mommie says you’ve been very good to Father Jan. Why were you so good to him?”

I paused a moment, savoring my thoughts, then gently squeezed her little hand. I looked down at her bright inquiring eyes and softly repeated a much-loved phrase from a Robert Frost poem: “Because, little one,” and I stroked her tawny hair, “he was a promise I made to myself, I had to keep, in the many miles -- God willing -- I have to go before I, too, sleep.”

She nodded her head, satisfied, tilted her pretty little chin and flashed a charming enigmatic smile -- for all the world as if she knew just what I meant -- then she bent over, picked up another bright leaf to mark the day, and with matching smiles, we skipped our way to the car . . .

|

Cherish . . . |

Dorothy V. Corson

Feast Day of Our Lady of The Rosary

October 7, 1975

|

|