Notre Dame's Grotto / by Dorothy V. Corson

A Living Legacy

The Empress Eugenie Crown and the six-foot bronze crucifix were among many beautiful gifts given to early Notre Dame by Napoleon III and his Empress Eugenie. However, they were all surpassed by another extraordinary gift they were not even aware they had given. It was to become a living legacy -- an intangible gift -- that would benefit people at Notre Dame and throughout the world. For centuries their names were destined to be linked with the Our Lady of Lourdes Grotto at Lourdes and Notre Dame:

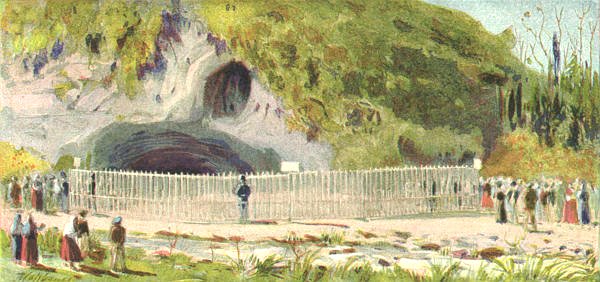

Ultimately, Emperor Napoleon III himself intervened to have the barricades removed from the grotto of Massabielle.

Their part in the drama that unfolded at Our Lady's Grotto at Lourdes in 1858, links them forever with its mystery.

These facts were confirmed, not only in the 1875 book, Our Lady of Lourdes, written by Bernadette's historian, Henri Lasserre; but also in Franz Werfel's book, The Song of Bernadette, based on Lasserre's book 80 years later, which became a classic award winning film.

Lasserre records this episode at the Lourdes Grotto during the time it was barricaded and guarded. The Mayor of Lourdes issued a proclamation. The public was forbidden access to the Grotto. Anyone trespassing on the Grotto grounds or taking water from the Spring would be prosecuted according to law. "Illustrious personages," Lasserre relates, "sometimes transgressed the limits of the enclosure":

. . . a lady had passed the boundary a few paces behind and had gone to kneel against the barrier of boarding which closed the Grotto. From between the opening of the palisade she was watching the miraculous Spring gushing forth and was praying. What was she demanding of God? Was her soul turning itself towards the present or the future? Was she praying for herself, or for others who were dear to her and with whose destiny she was charged? Was she imploring the blessings' and protection of Heaven for an individual or a family? No matter.

This woman engaged in prayer had not escaped the vigilant eyes which represented the policy of the Prefect, the Magistracy and the Police.

The Argus . . . rushed towards the kneeling woman. "Madame," said he, "nobody is permitted to pray here. You are taken in the very act; you will have to answer for this before the Fuge de Paix, presiding over the Correctional Tribunal, and without appeal. Your name?

"Willingly," said the lady, "I am the wife of Admiral Bruat, and Governess of His Highness, the Prince Imperial." . . .

No one in the world had a higher respect for the social hierarchy and established authorities than the formidable Jacomet. He dropped his accusation.

Lasserre does not pursue this interesting factual account further. Werfel, however, eighty years later, proposes -- perhaps by Lasserre's account or further research -- that Madame Bruat by her very admission that she was the Governess of the Imperial Prince, may have been there at the bidding of her Mistress the Empress Eugenie in behalf of the two-year-old Crown Prince, only child of Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie, who might have been ill. And that perhaps the very devout Empress Eugenie's influence may have had a great deal to do with the Emperor's change of heart, from stoic disinterest to immediate action. A decree was dispatched "directing that for the future the people should be allowed perfect freedom of action."

Lasserre describes the jubilation:

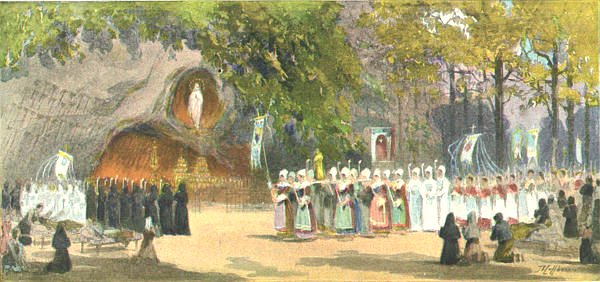

The town of Lourdes was in a great state of emotion. During the afternoon, the crowd kept going to and fro on the road leading to the Grotto. The faithful, in countless throngs knelt devoutly before the Rocks of Massabielle. They sang canticle, and recited the litanies of the Virgin. Virgo potens, ora pro nobis. They quenched their thirst at the Spring. The believers were free, God had achieved a victory.(109)

Napoleon III and his Empress Eugenie, without knowing it, had given their first gift, an everlasting one, to the University of Notre Dame -- the Our Lady of Lourdes Grotto.

Our Lady had inspired a peasant girl, and moved an Emperor and his Empress -- worlds apart from one another -- to make a difference in the lives of millions of people. Without their actions, the Grotto at Notre Dame would not have existed, because there would have been no Our Lady of Lourdes Grotto in France to inspire it.

Bernadette's experience is expressed in a beautiful hymn at the end of an undated 19th century book about Lourdes. The beginning seven verses and its ending follow:

|

The hour had come for evening prayer;

A hidden Angel walked and met

Across the mountain stream she hied.

Sudden it shook her, sudden it fell.

She saw the tender and gentle face

It was the Mother of God who smiled

Clad in white was the Lady chaste,

The sick, the mourner, the forgiven

|

Bernadette was 35 years old when she died. In the movie, Song of Bernadette , her faithful parish priest speaks to her at her bedside:

You are now in Heaven and on earth, Oh Bernadette.

Heaven chose you . . .

Now there's nothing you can do except choose Heaven.

Alain Woodrow concludes an impressive article in the 1994 Catholic Digest entitled, "LOURDES, More Popular Than Ever," with this moving tribute:

Bernadette was not theologically sophisticated. But she nevertheless grasped the essential message of the Gospel. "See how simple it is," she said on her deathbed at Easter, 1879. "All you need is love." That is the true miracle of Lourdes.(111)