Notre Dame's Grotto / by Dorothy V. Corson

The Kintz Family Enters the Picture

The southern portion of the Talley/Chirhart property ended just south of the Toll Road on Juniper Road. Juday creek meanders through the southwest corner of the property. In the late 1800s the creek was simply referred to as The State Ditch. Earlier yet, on an old 1863 map, it was designated as Sheffield Creek.(136)

In 1888, the county decided the creek needed to be straightened, dredged and widened. The people who owned the land the creek passed through, were to be taxed accordingly. Jacob died in 1885. Mary Talley Chirhart and her children were disturbed at this charge and forfeited the land rather than pay the taxes. Father Thomas Walsh, then president of Notre Dame, bought the 80.10 acres containing the creek at a Sheriff's sale on May 5, 1888.

On January 5, 1891, Father Walsh sold the property to Peter Kintz II and his wife Mary on a Warranty Deed. The loan was secured with a payment of $1600 on January 5, 1891, with the remainder to be paid in four promissory notes with a 7% annual interest. The deed was paid off on December 15, 1900 and the University of Notre Dame released the mortgage to Peter and Mary Kintz.(137) Kintz Drive, on the east side of Juniper Road, runs down the middle of the 80 acres of land they bought from Father Walsh.

The Kintz genealogy refers to a Kintz son who worked for the Summers family for a year to help pay the mortgage. Gabriel Summers was into real estate and farming. He owned adjacent land south of the Toll Road, now Indian Village, and West of Juniper known as Summers Woods and Oakmont Park.(138) In later years, much of the Summers land was bought by Notre Dame. An 1863 map shows that Sorin once owned the portion of land along Juniper Road now known as Indian Village.

When Peter Kintz died his 80.10 acres of the original Talley/Chirhart land was passed on to his surviving eight children, each receiving 10 acres. Some time in the late 1930s, 10 acres owned by Cecelia Kintz, who was married to James Luther, were bought by Alden Davis, a Notre Dame Professor, one of her boarders. He purchased the old Summers barn and moved it from the Indian Village area to its present site south of the old Talley/Chirhart home, on the creek at the corner of Juniper Road and Kintz Drive. It was remodeled into the picturesque dark brown rustic homestead that now graces the winding path of Juday Creek. As late as the early 1950's sheep could be seen grazing on his grounds. As the story goes, he eliminated lawn mowing by using them to keep the grass clipped. The present owners, William J. and Linda Conyers, have added their own charming touches to the Conyers Cottage. An arched Monet bridge constructed by William J. and his brother, Father Richard J. Conyers, C.S.C. now graces their water gardens.

When Peter Kintz died his 80.10 acres of the original Talley/Chirhart land was passed on to his surviving eight children, each receiving 10 acres. Some time in the late 1930s, 10 acres owned by Cecelia Kintz, who was married to James Luther, were bought by Alden Davis, a Notre Dame Professor, one of her boarders. He purchased the old Summers barn and moved it from the Indian Village area to its present site south of the old Talley/Chirhart home, on the creek at the corner of Juniper Road and Kintz Drive. It was remodeled into the picturesque dark brown rustic homestead that now graces the winding path of Juday Creek. As late as the early 1950's sheep could be seen grazing on his grounds. As the story goes, he eliminated lawn mowing by using them to keep the grass clipped. The present owners, William J. and Linda Conyers, have added their own charming touches to the Conyers Cottage. An arched Monet bridge constructed by William J. and his brother, Father Richard J. Conyers, C.S.C. now graces their water gardens.

Many early priests, most especially Sorin, financed their religious endeavors by buying and selling land. It was a skill they passed on to one another. An article entitled, "Stories of Two Remarkable Priests - - Benoit And Sorin," by Bishop John M. D'Arcy, explains how Father Julian Benoit founded St. Augustine Parish on what is now the grounds of the Immaculate Conception Cathedral in Fort Wayne:

In addition to the Cathedral, he bought land for churches and built churches and schools throughout the area. Yet he died penniless. How did he do it? Indeed, during his later years, Pope Pius IV, aware of his business sense, asked him this question: "How do the priests in America make their living?" Father Benoit, from his early days in Fort Wayne, saw that money was being made in land speculation. So he would buy land, very reasonably, and later sell it for a profit. With the money he received, he would buy further land for churches and, indeed, build churches.(139)

The article goes on to mention that Father Benoit and Father Sorin were good friends. When Father Sorin was in deep financial trouble at Notre Dame he turned to Father Benoit for loans. This land speculation must have been a skill Sorin also learned and passed on, as President Walsh's purchase of sheriff's sale land and its resale to the Kintz family, at a tidy profit, indicates.

The family story is told that Peter Kintz's youngest son, Ott, as a very young lad, weeded and replanted, with a hand planter, the corn that had fallen or been eaten by crows in the field where the Athletic and Convocation Center is now. The older Kintz sons worked as carpenters at Notre Dame and, as the family story goes, hauled stone and worked at the Grotto as part payment on the mortgage with Father Walsh; a reasonable assumption since the Grotto was being built midway in the mortgage.

This was not an uncommon practice. One man paid for his son's college education by building the spire of the church.(140) Another entry in the Scholastic refers to the building of the original church:

An appeal was made to the few Catholics around, if they could or would do a little -- most of them were poor, many not very fervent. However a subscription was made: it was paid in labor.(141)

One sentence in Father Maguire's letter also mentions this practice. Speaking of the building of the Grotto he says:

The boulders were gathered from our farms and others surrounding it.

Confirmation of the above statement was offered by Father Joseph Rogusz. He remembers being told by Brother Peter Claver Hosinski, (1872-1958) that he and other Holy Cross Brother novices hauled stone for the Grotto.

In the same 1896 ledger, a $26.35 payment is recorded for stone brought to the campus by the contractor, John Gill. Two other unnamed entries were paid $5.90, and $51.60 for 83/5 cords of stone at $6.00 a cord. Stone was measured like wood then. A pile of wood 4 feet wide by 4 feet high by 8 feet long was a cord. These two unnamed entries might have been stone brought by the Kintz family and their payment was applied to their mortgage. Unfortunately, there are no University records of payments on the Kintz mortgage, by cash or barter, still in existence to verify this family story.

Stone was also brought on a stone boat by O. P. Stuckey, who was paid $13.66. O. P. Stuckey's home and barn are still standing beyond the Francis Branch library and the Greek Orthodox Church on Ironwood Rd. The old Stuckey School stood on the Northwest corner of Ironwood and Douglas surrounded by a fieldstone wall, all of which has long since disappeared. In 1890, O. P. Stuckey and his team of horses were killed, struck by lightning in a field on his farm. However, he had a granddaughter named June Turnock. She became June McCauslin, the Financial Aid Director at the Notre Dame Campus for 18 years until her retirement. She also passed on another family story. Her Grandfather Turnock plastered the interior of the Dome.

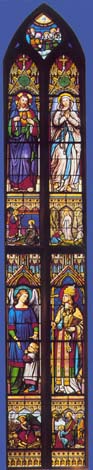

Many area families were well represented in their donations to the stained glass windows and bell. The family of Peter Kintz donated a stained glass window for the church and gave money for the bell. Louis Gooley, related to the Kintz family, also donated a stained glass window for the church and contributed toward the bell, as did the Chirhart family who owned the Talley land. Another member of the Gooley family was said to have hauled the clapper for the bell to Notre Dame in his mule cart.

A reference to the donation of one of those first stained-glass windows was printed in an 1876 Scholastic. It records another bit of history and also explains why it was a special privilege to be associated with a church in this way. It appeared under the title, "Gift of the Edward Mulligan Family:"

The above inscription, printed in large characters on a golden scroll at the bottom of a stained-glass window in the new Church of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, brings back to our minds "the Ages of Faith," when crowned heads and princes of Christian blood, as well as the common faithful of inferior rank, esteemed it a singular and precious privilege to see their names immortalized, as it were, the moment they were accepted to be recorded on the walls or pilasters, or on stained-glass windows in the House of God.

Thus, indeed, many a name has been handed down from remote antiquity, to the notice and praises of subsequent centuries, which otherwise would have been long since totally forgotten.

In those happier days of piety, it was justly considered a greater honor to leave such lasting evidence of generous munificence towards God's own House than large estates, or coffers filled with gold, or the coveted wealth the end of all which was so soon to be met in a coffin, save what was done for God's honor and glory.

Time then, as ever, often made woeful changes in human fortunes, and frequently, as even now, great landlords fell from the pinnacle of high offices and honors to the ordinary walks of society; and yet, when reverses had leveled all, the stained glass of a modest or of a grand Church, revealed and transmitted to succeeding ages the lovely evidences that such a family had left an imperishable record of their religion, and their grandsons and nephews could walk into their generous ancestor's temple without a blush, if they had preserved their faith, or keep their heads down, if they had abandoned it. Thus it is that honorable names, long since gone from our midst continue to speak to their descendants the eloquent language of their glorious Faith.

We feel rejoiced that the honor of the first one of these magnificent and classical windows has been secured by the pious family whose name is there inscribed for ages. Mr. Edward Mulligan, now deceased, has left a family worthy of himself. Thirty-five years ago, [1841] to his last moment in 1868, he remained Father Sorin's best friend. His memory is held in esteem and affection by all his acquaintances, and it will be a pleasure to see in this stained-glass window the evidence that his family hold in honor the virtues which he left them as a rich legacy.(142)

Mary Grix, another local resident, said her great grandfather, Patrick Mulligan, owned a 200 acre farm that went from U.S. 31 to Laurel Road. The family purchased the land in the early 1800s. Mary is still living in a home built on his land. He also loaned money to Notre Dame in the early days and his name is engraved on the bell. When he died the church was draped in black. She said he was very fond of the Grotto and never left the campus after church on a Sunday morning without stopping to say a prayer and take a drink at the fountain.

It was now very much in evidence that many farmers and townspeople of the day helped their neighbors, Notre Dame and St. Mary's.