Notre Dame's Grotto / by Dorothy V. Corson

A Visit With Mme. Coquillard

The missionary priest goes on to mention a visit to the nearby home of Mme. Coquillard. He describes his admiration for the young adopted Indian he meets there.

During my stay in South Bend I was sitting one morning in the Coquillard family's parlor and talking with the little son of the household when suddenly a handsome, slender, young Indian came in. The strongly built child of the forest came into the room with dignity and moved freely and without inhibition on the expensive carpets of my friend's parlor, as if he was always used to the luxury of refined England. . . . The young Indian was very well dressed: He wore perfectly tight-fitting leggins -- that means "leggings" or a kind of two-part trousers worn like long stockings and tied to the hips with string. These leggings were decorated on the outside with a wide border that stuck out a little. Over them a clean shirt hung down to the knees, fastened with a leather belt around his hips like the dust coats of our students. In his belt he had a bowie knife and on his feet he had fine moccasins (Indian shoes) cut from soft deer hide, like tobacco pouches in the shape of feet, sewn together only on the instep. Because of its lightness and softness this kind of shoe is very beneficial for the silent walk of the quick-footed, cunning savage.

The moccasins of this young Indian were moreover decorated with embroidered leather trimmings, which covered the ankle and almost the whole upper part of the shoes. Such was the squaw's embroidery; nobody would expect such neat needlework from savage Indian women. His well formed head was bare; his shiny black hair was combed from the front to the back and fell down his neck; his glowing jet black eyes were focused on me, the "Father". (With "Nose", Father, as I already mentioned, the converted savages address the missionary.) And as he stepped closer to the Father with graceful posture, he knelt down to receive the blessing of the "Blackrobe" and asked me to accept the present which he presented in the name of the Indian band that had sent him. It was a very big, just recently shot, and already totally cleaned turkey . . . .

He then relates this incident -- the sad story of another young Indian -- told to him by Mme. Coquillard. In recounting the story to him she touches on the subject of vengeance and explains the Indian's belief in justice. Mme. Coquillard, who was reputed to be part Indian, was an interpreter for Badin, DeSeile and Sorin. This disturbing incident is reminiscent of the legend of the sycamore tree:

When Madame Coquillard noticed my obvious admiration for the handsome build and fine figure of an Indian young man, she told me that not long ago in the vicinity one such well built young Indian had been killed by his own grandmother. The young man had killed an Indian from a different tribe in a state of great excitement. Shortly after the crime had happened, the murderer regained consciousness and, knowing well that according to pagan Indians' laws of vengeance, his life became forfeit to the family of the murder victim, he fled and disappeared. The vindictiveness in the hearts of the Indians, where the power of Christianity hasn't reached yet, is unbelievable. If they die before they can get hold of their desired victim, they leave the execution of the revenge plan as the holiest tradition for their offspring, which they couldn't carry out because of the lack of opportunity. So unsatisfied feelings for revenge pass on to several generations. Now the family of the murder victim demands from the family of the murderer a reconciliation sacrifice, which cannot consist of anything other than the extradition of the murderer himself or another member of his family related by blood. If a relative of the murderer had surrendered himself, the shame of the murder and on top of that the shame resulting from his weakness of character, because of the penance he failed to do, would have remained on his head, and even his relatives would have looked upon him as an outcast. Considering all this, the grandmother of the murderer knew how to lure her grandson out of his hiding place, and they met in the vicinity of Mr. Coquillard's house.

The grandmother, a strong, vigorous Indian women, now told her grandson, since he had to die, it would be more honorable to be killed by her than to die the death of revenge under the humiliating hands of the enemies who were pursuing him -- and saying this, she stuck her knife in the chest of the unsuspecting young man. The grandson quickly breathed his last, and the grandmother's barbaric sense of honor was satisfied. But now nature also claimed its rights towards that woman. As she saw the young man lying on the ground in his blood, she raised such an outcry of lamentation and such howls of mourning that the stones of the valley and the trees of the forests asked to mourn with her. She fell down on the grandson, tearing her hair, pounding her chest, stamping her feet on the ground on which the corpse was lying. This severe pain passed into a frenzy which lasted almost a whole day. The other relatives also came by and helped to complete the dreadful picture of furious agony. A messenger was sent to the family of the murder victim by the family of the grandson -- the reconciliation had been accomplished. "This scene of agony," said Mrs. Coquillard, "is always fresh before my eyes; the impression she had on me is indelible. I was suffering badly and couldn't at all get the howls of mourning out of my ears. Thanks be to God, who sent the missionaries to relieve them from such scenes."

The visiting priest explains how Christianity was transforming the Indians attitude toward vengeance:

At this remark, I myself appreciated the divinity of the Christian faith, which is capable of making gentle children and lambs out of brutes and hyenas. Indians, even the most frantic men, give up their vindictiveness, which had been part of them for all times, once they have sworn allegiance to the banner of Christ.

. . .

These wild children of nature with their otherwise sharp and glaring physiognomies had now with the enjoyment of the Lamb nothing but faces of saints. Their black eyes bathed in tears, which rolled down their copper red cheeks in big and heavy pearls; a kind of transfiguration was poured out across their faces, which showed the pagans the power of the faith and showed the faithful the inner sun of grace, which shone out of the hearts of these inhabitants of the forest who had been innocent since their baptism.

A greater humility, a higher decency, a firmer faith and a deeper worship can hardly be found anywhere than in these natives of America in the church at Bertrand, which became apparent to the astonished and ashamed descendants of Europe. This edifying behavior of the Indians also prevented them from being derided and ridiculed by the different-minded residents of Bertrand, when they knelt in front of the priest to receive his blessing if they met him somewhere in the village, which they did with a special trust in the "Great Spirit".

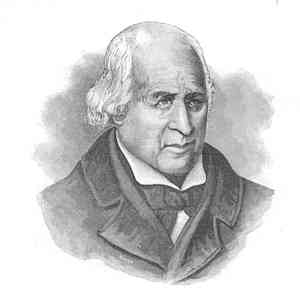

A striking example of the influence of the early missionaries in this regard is the description of such an incident related by Badin himself when he first came to St. Marie des Lacs and which he sent by letter, as requested, to the Bishop:

The late good Bp. Fen[wick] of Cincin[nati] having desired me in May last, to give to the Ind[ian] Department occasional information of considerable events and other subjects respecting the tribe among whom I reside, I shall begin relating the circumstances incident to a murder which took place last Spring, soon after my return from Cincinnati.

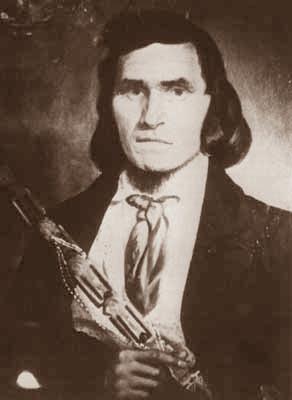

On the 9th day of last June, Topinabee, a man of about 25 years of age, chief of the whole tribe of the Pout., who would not listen to religion, did in a drunken fit kill Nanankoy, a man justly esteem'd in the nation -- The murderer surrendered at a council held at Carey on the 11th June and looked with resignation for the punishment with the drawn and glittering knives of the brother and friends of Nanankoy.

A sinister silence followed after some peaceful speeches of Pokagon [an elder Chief of the Potawatomi]. My interpreter [Angelique 'Liquette' Campeau], an old woman of 68 years of age, much respected and beloved by the Indians, after unsuccessful attempts to avert a vengeance, which probably would have provoked many other murders, disarmed the men by generously offering her own life in these words addressed to the sullen and indignant brother of the deceased. "Kill me, I stand here to be killed in lieu of Topinabee."

The brother stunned by this unexpected effort of charity, consented to delay inflicting the deadly blow and having been also brought by the Agent (Col. Stewart), from council to a private conversation he resolved to refer the decision to a certain chief, his near relative and to a pretended prophet on the Wabash who gave a bloody answer. But before coming to the dreaded execution several long talks were held with me where I made them so sensible that the prophet was not the son of God as he pretended to be that they laughed at his impostures and their own credulity. Finally a council was held on the 29th June, to whom I addressed the following letter, and it was agreed that Topinabee would be redeemed by making certain presents to the family of the deceased. All the red with some white brethren contributed to assist the chief in paying the price of redemption. -- It may be remarked here that Topinabee had come to me on the 17th June fallen [fell?] on his knees [and] promised me in the presence of God to drink no more whisky and he has been faithful to his promise.

Following is the speech on the evils of whiskey and the futility of killing Topinabee which Badin delivered to those assembled at Carey Mission, Niles MI on June 29, 1832:

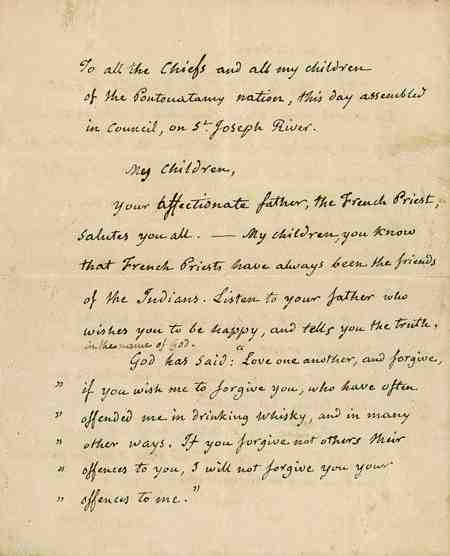

To all the Chiefs and all my children of the Poutouatamy nation, this day assembled in council, on St. Joseph River.

My children, Your affectionate father, the French Priest, salutes you all, -- My children, you know that French Priests have always been the friends of the Indians. Listen to your father who wishes you to be happy, and tells you the truth, in the name of God.

God has said: "Love one another, and forgive, if you wish me to forgive you, who have often offended me in drinking whisky, and in many other ways. If you forgive not others their offenses to you, I will not forgive you your offenses to me."

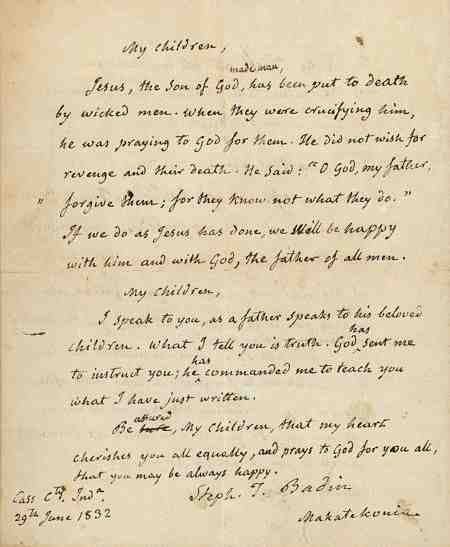

My children, Jesus, the Son of God, made man, has been put to death by wicked men. When they were crucifying him, he was praying to God for them. He did not wish for revenge and their death. He said "O God, my father, forgive them; for they know not what they do." If we do as Jesus has done, we will be happy with him and with God, the father of all men.

My children, I speak to you, as a father speaks to his beloved children. What I tell you is truth. God has sent me to instruct you; he has commanded me to teach you what I have just written. Be assured, my children, that my heart cherishes you all equally, and prays to God for you all, that you may be always happy.

Cass Cty. Inda.

29th June 1832

Steph. T. Badin

Makatekonia

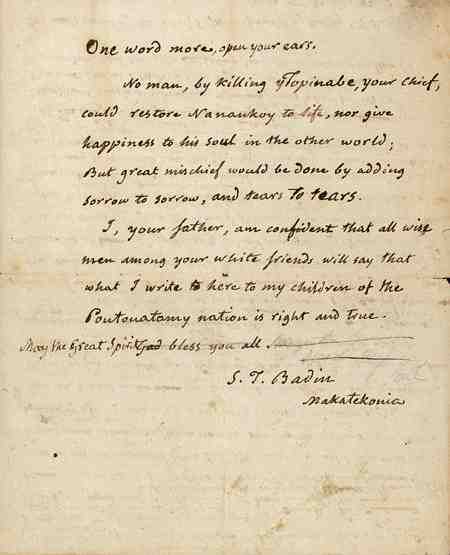

One word more, open your ears.

No man, by killing Topinabe, your chief, could restore Nanankoy to life, nor give happiness to his soul in the other world; But great mischief would be done by adding sorrow to sorrow, and tears to tears.

I, your father, am confident that all wise men among your white friends will say that what I write here to my children of the Poutouatamy nation is right and true.

May the Great Spirit bless you all.

S.T. Badin

Makatekonia(207)

This impressive document, the original of the above letter, is preserved among Father Stephen T. Badin's papers in the University of Notre Dame Archives. A testament to the early French missionaries' care and concern for the welfare of the Native American Indians who relied on their revered Blackrobes for Christian counsel.

Father Badin wrote of his interpreter, Angelique, whose actions saved the life of Chief Tobinabee: ". . . I do not know of a priest more industrious, more penitent, more patient, more learned, more genuinely pious then she is in all this country" [Quoted in Buechner, The Pokagons, page 302].