Painting of Rockne by Curt Sochocki ©

Unsolved Mystery Surrounds Rockne’s Ill-fated Plane Trip to California

Every now and then a story comes along that begs to be shared, if for no other reason than the wonder of all the uncommon coincidences and circumstances that have brought it to life again seventy years -- almost to the day -- after this tragic event occurred. This is one of those stories.

On May 2, 2002, I received an unexpected email from a fellow researcher I met in the University Archives during my research there on the Grotto. Paul Gullifor, a communications Professor at Bradford University in Illinois, had just published the book he had been researching when we first met several years ago.We had been keeping in touch via occasional emails since that time. When we first became acquainted and he told me that football broadcasting would be the focus of his first book, I showed him my research on a unique advertising promotional stunt associated with football broadcasting that I had stumbled upon during my research. I thought it might be an interesting highlight for his book.

It concerned a Miniature Parachute Bread Drop that occurred during one of the first games broadcast on radio in the newly built 1930 Notre Dame Stadium. Paul was as intrigued with the story, as I had been when I first heard about it, and he decided to mention it in his book, The Fighting Irish on the Air: The History of Notre Dame Football Broadcasting. Click on the green link above to see the complete story with illustrations.

Now he was returning the favor by sending me another of those extraordinary -- too good not to be shared -- stories. He said he had just received the story from his mother. It was a story associated with Rockne’s plane crash that was hard to believe and he was sending me a copy of it. Knowing I love a mystery, he knew I would not be able to resist researching it. “Let me know,” he said, “if you learn anything more about it.” I assured him I would.

When I read it, I also found it hard to believe, but it immediately piqued my curiosity and my archival detective instincts. And it did sound plausible. Unfortunately, it was also a story that needed to be re-searched and validated to establish, if possible, its credibility. I knew that would take some doing, but it was a challenge I could not resist. Some of the most unlikely research projects I have undertaken have become the most promising archival adventures. How could I let a story like this one -- about a Notre Dame legend -- go unchallenged? I had to investigate it thoroughly, if for no other reason than to satisfy my own feelings about it.

But first I needed to know how this story from a 1977 book mysteriously found its way into Paul’s hands almost 25 years after it was published. So that was the first question I asked him. Paul told me his mother, Rose, who lives in South Bend, his hometown, had sent it to him, and she would be able to tell me how she happened upon it.

“Felix, the barber”, she said, had given it to her, and he said he had gotten it from Achilles “Chick” Maggioli, a former football star at Notre Dame, who had also played professional football with the Detroit Lions.

“Chick” Maggioli, in his early 80s, was recovering from recent surgery for old football injuries when I called him, and he welcomed a telephone visit. I thought for sure the trail would end there, but he told me he had gotten it from Agnes Hagerty, one of the Hagerty twins, who were both librarians, now retired. Ruth worked at the Hesburgh Library on the Notre Dame campus for 40 years, and Agnes worked at the St. Joseph County Public Library for twenty years. So it took just one more telephone call to solve the mystery of how this story, written in 1977, had come full circle back to Notre Dame where it originated.

Agnes Hagerty, the sister I spoke to, told me that one day in cataloging books at the downtown library she noticed a book whose title sounded interesting to her, and she decided to check it out and take it home with her. The title of the book, from which the story came, she said, was Made in Hollywood. It was written by a man named James Bacon who was a former Associated Press reporter and later a Hollywood columnist. She said the book was very entertaining, but it was this particular story about Rockne that got her attention since Notre Dame played a big part in her family’s life.

Agnes Hagerty, the sister I spoke to, told me that one day in cataloging books at the downtown library she noticed a book whose title sounded interesting to her, and she decided to check it out and take it home with her. The title of the book, from which the story came, she said, was Made in Hollywood. It was written by a man named James Bacon who was a former Associated Press reporter and later a Hollywood columnist. She said the book was very entertaining, but it was this particular story about Rockne that got her attention since Notre Dame played a big part in her family’s life.

She was so impressed with it that she even hunted in used bookstores until she found a copy she could purchase for herself. The copy she bought not only had the original book jacket with it, it was also autographed (in red) by the author: “Best wishes, James Bacon.”

From that book she made the copy that she gave to Chick Maggioli, who gave a copy to Felix the Barber, who gave one to Paul’s mother, who sent it to Paul, who made a copy and passed it on to me. Agnes Hagerty knew nothing more about it, except that she thought it was an amazing story worth sharing. And typically, being a librarian, she had included all the factual information about the book with the article that had been passed from one person to the other.

It was “Chick” who also acquainted me with a most unusual book, pictured at the beginning of this story, printed by Blue & Gold Illustrated in South Bend, IN. It turned out to be a heaven-sent piece of good luck concerning my research. This large impressive paperback book is filled with an amazing collection of newspaper articles, poems, and memorabilia about the plane crash and the funeral, that appeared in publications after Rockne’s untimely death. I couldn’t have asked for a more complete array of information about Knute Rockne to base my research on.

These articles were saved in a scrapbook by Clement Miller, who was 89 years old when I talked to him over the telephone a year ago. Clement told me Robert Firth, the retired owner of Blue & Gold Illustrated in South Bend, was his the brother-in-law. When the 100th anniversary of Rockne’s birth came along, Mr. Firth chose from Clement Miller’s scrapbook a compilation of the best articles to print in book form to celebrate the occasion.

The most surprising part of the story, to me, was the fact that James Bacon, the author of the 1977 book in which the story about Rockne appeared, was a Notre Dame alumnus. He was a sophomore in St. Edward’s Hall in 1934 when he first heard the story which he later recounted in his book. He was with a fellow student, Kitty Gorman, a noted football player at the time, who was also a resident of St. Edward’s Hall. They had gone together one evening to visit Father John Reynolds, the rector of the hall, in his office, and it was he who told them about his hair-raising experience in Chicago.

A check with the Province Archives Center revealed that Fr. John Reynolds had passed away in the mid 1980s. The football player, Kitty Gorman, was also deceased, which left just the author of the story yet to locate. If he was also deceased my search would be at a dead end.

However, the alumni office confirmed that he was alive and still living in California. To be thorough I wanted to read the entire book before I attempted to contact him. I checked the St. Joseph County Public Library to see if the book might still be there, but it was not. However, a library friend in the Interlibrary Loan department located it at another library and ordered it for me. In the process, she told me, she found two other books by the same author about Hollywood and the entertainment business. One was about Jackie Gleason, and James Bacon was his official biographer.

And to make things simpler she said they had them at the Notre Dame Library! Of course. Why hadn’t I thought of that? After all, he was a Notre Dame alumnus. By now, I was testing his name with everyone I had dealt with at Notre Dame during my 12 years of research, even editor friends at the Notre Dame Magazine and the ALUMNI Newsletter, but without success. No one seemed to know anything about him, but everyone I spoke to was interested in learning more about him.

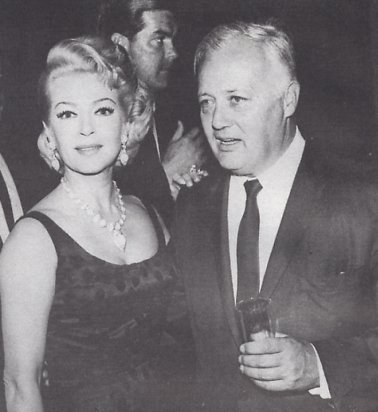

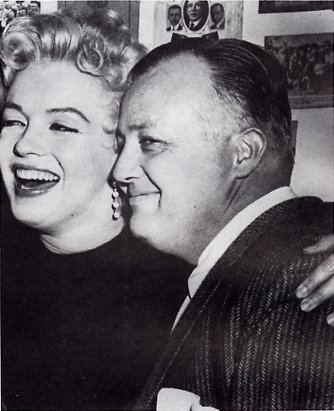

All three books I found fascinating reading. One in particular was filled with photographs of James Bacon with the many famous movie stars he has associated with during his long career in the entertainment business. It very soon became apparent that he has a terrific memory for details -- what is called total recall -- that has spanned his entire lifetime. He is also a man of the world who lived a fascinating life in dealing with famous people all over the world. He traveled with Bob Hope on numerous overseas trips after World War II and progressed from an Associated Press Reporter to a noted Hollywood columnist. He is also an award-winning journalist.

Clint Eastwood said this about his first book, Hollywood is a Four Letter Town: “Jim is about the only journalist I know who is ever permitted behind the scenes in Hollywood. The book Hollywood has been waiting for. It’s a blockbuster!” And Lucille Ball added this compelling statement. “ It’s a great book because it was written by the man who was there when it all happened.”

And in the case of this Rockne story, James Bacon was told the story by a priest “who was there when it all happened.” And yet, no one now at Notre Dame was aware of his background, though he must have been present at many Alumni Reunions over the years. I did learn later on that Father Joyce was a classmate of his and met with him at the last Alumni Reunion, but even he had not known about his background or that he had written any books. When I shared the Rockne story with Father Joyce he asked me for a copy and said he expected to meet with Jim at the reunion in June since they would both be among the oldest alumni in attendance.

The cover of James Bacon’s book also describes him as an internationally syndicated columnist and TV personality. The deeper I got into the background of this buried Rockne story the more interesting it became. And I knew I wouldn’t be satisfied until I followed every clue till there were no more clues left to follow.

Next step, locate James Bacon’s most recent telephone number in the Notre Dame Alumni Directory and see if I could talk to him personally about the story. Two recent numbers listed in the directory were the wrong James Bacon. I made one last attempt using what was an older listed number in the directory, and to my surprise the person on the other end of the line was the James Bacon I was looking for. A delightful man, then 86 years old, with an openly friendly and hospitable personality that projected immediately over the phone.

He was surprised to learn how I had happened upon his Rockne story and verified that the story about Fr. Reynolds' hair-raising experience with the Chicago mob was factual -- he never doubted the story -- but that as to proving it beyond a shadow of a doubt all these years later might be difficult with most of the principal players being deceased. He wished me luck with my research and thanked me for my call.

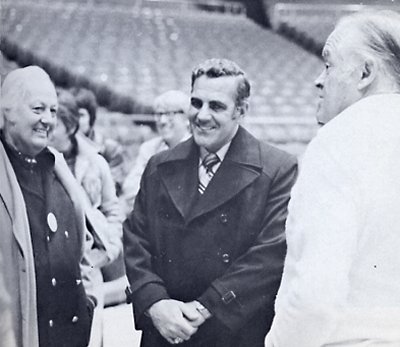

I happened to be doing research on campus during the reunion activities and upon leaving the campus decided to see if I might be able to leave a message for James Bacon at his host dorm behind the Morris Inn. It was nearing 4:30 p.m. and the dorm door was locked. However, just as I turned to leave, another visiting alumnus unlocked the door for me. I walked over to leave my telephone number for James Bacon at the desk, but the student picked up the phone and called his room instead. Coincidentally, or providentially, he happened to be there, and when she gave him my name he told her he would be right down.

Meeting him in person was a particular pleasure. It also gave me the opportunity to ask a few more questions and update him on my efforts. It wasn’t long after that meeting that I was watching an A & E television special on the death of Marilyn Monroe and I found myself gazing at James Bacon being interviewed about his friendship with Marilyn from starlet to super star.

Not long after that I saw him again on Larry King Live when the life of Marilyn Monroe from her arrival in Hollywood, until her untimely death in 1963, was being discussed by the people who knew her best.

Several trips to the Indiana Province Archives Center after my telephone visit with James Bacon produced only two photographs of Fr. Reynolds and very little correspondence. In one September 1976 letter to Fr. Reynolds, a Notre Dame administrator, Fr. Jerome Wilson, recalls being one of his students. He reminds him of how they once played golf together and tells him about other things going on on the campus at the time of his letter. Then, this totally off the subject paragraph, which appeared near the end of the one page letter surprised me:

We often think about you and the story is often told about the Jack Lingle murder case where, apparently, you were in the subway when he was killed. Maybe you could write and give us the real lowdown on that particular case or, perhaps, even to this day you don't like to think about it.

Unfortunately, Fr. Reynolds’ reply to Fr. Jerome Wilson, if there was one, was not in the few papers I found in Fr. Reynolds’ file. So it appears that the story Fr. Reynolds told to Kitty Gorman and Jim Bacon in 1934, and which Bacon recounted in his 1977 book, might be the only existing firsthand account of Fr. Reynolds’ experience with the Mob in Chicago. However, one of those students, James Bacon, who has total recall, went on to become an award-winning journalist and wrote the story Fr. Reynolds told them in his 1977 book. Following is the story James Bacon wrote about the visit he and Kitty Gorman had with Father John Reynolds in his room at St. Edward’s Hall where he was the rector at the time.

Back in 1934, my sophomore year at Notre Dame University, I heard a remarkable story one night from Father John Reynolds, CSC, the rector of St. Edward’s Hall, my residence hall on campus.

Kitty Gorman, the center on the football team, and I were in Father Reynolds' office drinking beer-- a strict violation of university rules for students.

But Kitty was an unusual student. He had come up through the Notre Dame Minims, once the elementary and high-school arm of the university.

I don’t think Kitty had ever gone to any school in his life but Notre Dame -- from the first grade through law school

In 1934, the Minims were long gone but the memories weren’t. Kitty, as a one-time Minims student, could do no wrong with the priests at Notre Dame.

The ordinary student would be expelled if he had beer on his breath on a Saturday night. Kitty, whose room was next to mine and also adjoined Father Reynolds', could come in drunk (as he often did), cuss, knock over the steel wardrobe locker in his room, and generally raise hell all night.

Father Reynolds, a strict rector, never stirred when it was Kitty causing a commotion. He was a Minim, one of the chosen few still left at Notre Dame.

So that explains how I was in the rector’s office drinking beer: I came with Kitty.

Father Reynolds, who used to hoist a few himself in those days, told Kitty and me how he gave the last rites of the Catholic Church to Jake Lingle, the Chicago Tribune reporter who was killed by Al Capone’s mob in the heyday of Chicago gangland executions.

Lingle, often called the world’s richest reporter, was mixed up with the mob himself. He was the bagman who carried the payments from the Capone headquarters in suburban Cicero downtown to the crooked politicians and judges in City Hall and the Cook County offices.

Then Jake forgot to drop off a payment, or maybe he pulled off some kind of a double-cross. At any rate, he was standing on the Illinois Central platform at the foot of Randolph Street when he was executed, gangland style.

The Chicago, South Bend, and South Shore interurban railroad also used that station for its terminus on the two-hour run from South Bend to Chicago.

Just as the South Shore unloaded its passengers, Jake Lingle got his. Father Reynolds, on a trip to Chicago, rushed to the stricken Lingle and gave him the last rites, hearing his confession.

Father Reynolds didn’t even know whether Jake was Catholic or not. In fact, he had no idea who he was, just that he had been slain in front of the priest’s eyes.

It was all reported in banner headlines in all the papers. The story got wide play because it was one of the few times not counting innocent bystanders, that the hoods had not killed one of their own.

Of course, Lingle was one of their own, but the general public didn’t know that. To the public, he was a newspaper reporter for one of the biggest newspapers in the country.

Father Reynolds then told Kitty and me a horrendous tale of his harassment by gangsters, all of whom wanted to know what Lingle had divulged to him during that last confession.

The priest gave all of them the same answer -- that the seal of the confessional prevented his revealing what was said.

This only increased the phone calls and the mysterious visits. But Father Reynolds never told. Threats were made on his life and person. Still he never winced.

Then one day he was walking across the campus and bumped into Knute Rockne. The two chatted and the famous coach told the priest that Universal Pictures in Hollywood had just called him to make a fast trip to Hollywood.

The studio was making a movie called The Spirit of Notre Dame, starring Lew Ayres and Andy Devine, and needed Rock’s expert advice on some phase of the production.

Rock was moaning that he couldn’t get an airline reservation and would have to take the long train trip instead.

Father Reynolds said he had -- in his pocket -- reservations and tickets for a flight from Chicago to Los Angeles the next day.

The priest was in no hurry to get to Los Angeles and told Rock to take them. Father Reynolds would take the train trip.

Rock and Reynolds were old friends. Both had been track stars at Notre Dame. Rock was to football what Babe Ruth was to baseball in those days, a superhero of the Golden Age of Sports.

So it was not surprising when the banner headline around the world on March 31, told of Rockne’s death in a fiery plane crash over the Kansas farmland, near Bazaar.

A farmer, plowing his field, was an eyewitness to the crash, which also killed eight others. He said the plane exploded in midair, as if by a bomb.

Father Reynolds told us:

“My name was on Rock’s tickets and reservation. He didn’t have time to change them. And then all those threats on my life. Did those people plant a bomb on that plane for me? I don’t know. “I know if I hadn’t given Rock my tickets, he would have been alive.”

Last I heard of Father Reynolds, he was a Trappist monk someplace in Utah.

-- From Made in Hollywood by James Bacon, ©1977.

Used here by permission of the author.

Later in my research, I found this additional information about Fr. Reynolds in a 1972 Province Review during the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Fr. Simon’s ordination:

Father Reynolds was on the track team coached by Knute Rockne and set a 2-mile record in 1916. He also coached football, basketball, and track and played some prize winning golf.He was a popular teacher of history and a hall prefect and rector at Notre Dame before he joined the Trappists. He also gained considerable fame as a witness in the widely publicized Chicago trial following the “gangland” murder of Jake (The Barber) Lingle in the Al Capone era.

All this information I was keeping to myself until I could find more evidence to substantiate the story. And my next step would be to see what I could find out about the plane crash in the research materials at the University Archives. I was about to ask Sharon, the archivist, how to locate any newspaper articles they might have about Rockne’s death, when I noticed a small booklet about Rockne laying open on the counter just as she was about to hand it to me.

Another surprise: she said the archives had just gotten a request from a doctor in Arizona asking that same question I was researching, “Was Rockne’s plane crash really an accident?” Talk about synchronicity!

I had not told anyone about the James Bacon story I had received or my beginning research on the subject myself. Sharon was just beginning to make photocopies of news stories she had found for this man when I arrived so I was able to go over the newspaper articles myself.

On January 6, 1933 a Chicago paper carried this headline:

“Claim Rockne Plane Bombed by Gang to Get Lingle Witness.” Other headlines in other newspapers read, “ROCKNE DEATH LAID TO BOMB; ROCKNE CRASH PROBED BY U.S.” and, “Bombing Story is Scouted at Notre Dame.”

One article revealed that Fr. Reynolds testified on March 27, 1931 identifying the the killer as Leo V. Brothers.

Another newspaper story stated, “Rev. John Reynolds had booked passage on the same plane in which Rockne rode. For some minor reason, the priest cancelled the transportation.”

James Bacon’s story was not among any of the archival papers about Rockne’s death in a plane crash in Kansas. I now had some totally new information to add to their archival records.

It now seemed plausible that all these circumstances combined would have been reason enough for Fr. Reynolds to make arrangements to get out of town as soon as possible in case there were any repercussions from the trial. And returning to the campus the day before his departure would also have been logical. It would be a safe place to hide from any harassment he might encounter during the days immediately following the trial on March 27, 1931.

He could rest up from the ordeal of the trial on campus while he awaited the day of his departure scheduled for the evening hours of March 30, 1931. Instead, according to Reynolds, he met Rockne on campus and gave him his plane ticket to California. Which meant it was Rockne, who took his place, who boarded the night train to Kansas City to catch the plane for California.

Oddly, the night before I sat down at my computer keyboard to record this story, I was randomly checking the television channels before I went to bed when I happened to stop on the History’s Mysteries channel, and what they were showing caught my attention.

They were telling a story about Willie Sutton, the early 1950s notorious bank robber, escaped convict, and modern day Jesse James who had escaped from jail yet again using a fake gun he had meticulously fashioned and a face mask. This latest escape put him on the FBI’s Most Wanted list.

They then recounted the story of how an ordinary citizen, an alert young man named Arnold Shuster, recognized the fugitive bank robber and “dropped the dime” (as they put it) that led to his arrest. When Shuster later discovered there was a monetary reward for his information he laid claim to it, which brought his part in the arrest to the media’s attention. The program stated that when the underworld found out who had “fingered” Sutton the mob boss was incensed and determined to repay Shuster’s action with a professional hit. “I don’t like squealers! Take care of him!” A few days later Shuster was gruesomely gunned down in a back alley.

It was a timely reminder of the kind of risk Fr. John Reynolds took in identifying the killer in a courtroom. That alone might be enough to prompt underworld action against him, plus the fact that they may have thought that he had obtained more information about them during the dying newspaper man’s confession and last rites. Information that might at some later date be used against them.

When Fr. Reynolds told that story to James Bacon and Kitty Gorman in 1934, three years after the plane crash and his trial testimony, it may still have been a troubling time for him. Even if the plane crash had been an accident and not the result of a bomb, Fr. Reynolds might still have felt guilty about it.

As the last lines spoken by Fr. Reynolds in Jim Bacon’s story reveal: “Did those people plant a bomb on that plane for me? I don't know. I know if I hadn’t given Rock my tickets, he would have been alive [today].

All of which may even have influenced Fr. Reynolds' eventual decision to enter a monastery and become a Trappist Monk. Whatever the cause of the plane crash, it would have been a heavy burden to carry, knowing his act of kindness had taken another person’s life, especially the life of a legend like Knute Rockne.

In October 1944 Father Reynolds entered the Trappist Abbey of Gethsemani, Kentucky. Later that year he went to Huntsville, Utah, where he was one of the founders of the Trappist Abbey of Our Lady of the Holy Trinity. He recalls that he was the entire theological and philosophical faculty for the first four and a half years.

“In those days,” he says, “life was rugged and corn flakes frequent.”

Trappist Father Simon Reynolds then transferred to Our Lady of Guadalupe Abbey at Lafayette, Oregon, where he celebrated the 60th anniversary of his ordination on June 16, 1982.

James Bacon and Fr. Simon Reynolds had much in common. Fr. Simon also had a great sense of humor. In a paper he was asked to write about his background and vocation, dated August, 1972, he ended it this way: “To keep a mental balance, and my feet on solid ground, I feed the birds: wild birds (sparrows don't count; they are insolent). A bird writer writes, ‘You will succeed well with birds if you are prepared to admit that, in some things at least, they are much smarter than you are.’ Seems to me that fits humans, too.”

A pamphlet written about Rockne after his death in the plane crash shows this picture of Rockne wearing the numeral 13 on his football sweater. Beneath the picture are these words: “Every time Knute Rockne visited California, some accident befell. Just two years before, Rockne and his wife were speeding home from Los Angeles, staggered by the report that the life of their youngest boy, Jackie, was in peril after a peanut had become lodged in his lung. Before leaving on his fatal journey he asked: “Wonder what will happen this time?”

A pamphlet written about Rockne after his death in the plane crash shows this picture of Rockne wearing the numeral 13 on his football sweater. Beneath the picture are these words: “Every time Knute Rockne visited California, some accident befell. Just two years before, Rockne and his wife were speeding home from Los Angeles, staggered by the report that the life of their youngest boy, Jackie, was in peril after a peanut had become lodged in his lung. Before leaving on his fatal journey he asked: “Wonder what will happen this time?”

He wore the numeral 13 on his football sweater in practice, as a good luck fetish. When asked about the dangers of flying shortly before his departure on the plane trip that took his life. Rockne was reported as saying: “I don’t think it makes any difference. When a man’s time comes, he’s got to go, no matter where it is. It may as well be in an airplane as anywhere else.”

The article ended with these words: “He did with all his might that which it was given to him to do. He did not fight his fate. Knute Rockne is not dead. His was a spirit that does not die.”

How serendipitous that the story James Bacon wrote about Rockne for the book he published in 1977 would come to life again more than twenty-five years later. All of which would lead to the entertaining “L.A. Confidential” article about him that appeared in the Spring 2003 issue of the Notre Dame Magazine. The Spring issue was delivered on campus shortly after I finished this story.

James Bacon, soon to be 89, is still writing a column for the Beverly Hills magazine, and he still plays golf twice a week. The Seattle writer, Bob Cubbage, who was chosen to write the Notre Dame Magazine story about this illustrious alumnus and world traveler, told me that interviewing Jim Bacon was a memorable experience, that “he never had so much fun in his life!”

Here’s hoping James Bacon will share more of his fascinating life in another book. His entertaining way of telling his own life experiences and those of the countless famous people “he knew like a close relative” will be a record of an era that will never be repeated.

Knute Rockne was another of those legendary stars that flash across the sky like a comet and then are gone. Until the end of time, his tragic and untimely death in a fiery plane crash will invite speculation and introspection -- as one more legend and lore story surrounding the legendary Knute Rockne.

Was his untimely death by design or a tragic accident . . . only God knows.

Dorothy Corson

March 31, 2003

When I began writing this story I had no way of knowing how it would turn out. I just felt from the first time I read Jim Bacon’s 1977 book that it was a story worth retelling. It’s the kind of story that grabs you and just won’t let go until you tell someone else or do something about it yourself.

Ultimately, it was the strange way the story resurfaced after more than 70 years that could no longer be denied. Those few I shared it with along the way all urged me to research it and tell the story. And so, one night I put my pen to paper, so to speak, and my computer keyboard took off on its own. I decided if the story was meant to be shared, it would have to write itself. And then I would know that it was worthy of its place in history. And that’s exactly what happened.

Since none of these stories would have been written if I had not been a person who loves to know the story behind the story this is just one more piece of history that wound up in my lap. And so this story is where my research has taken me since that day an unexpected email arrived in my electronic inbox.

I’d like to thank everyone mentioned in this story, most especially, Agnes Hagerty and Rose Gullifor who started the ball rolling; Curt Sochocki who allowed me to scan his Rockne painting; and Jim Bacon who generously gave me permission to share his Rockne story and offered the photographs from his collection to illustrate it.

DVC