A Cave of Candles / by Dorothy V. Corson

Chapter 12a

The Madonna in the Lady Chapel

It was practically certain at the time of the robbery in 1886, that the Eugenie crown was safe, hidden away after the robbery to be returned later when the construction of the church chapels was completed. Probably, no one at the time suspected that it would take almost another three years before the chapel interiors were completely finished. Perhaps when the time came to replace it no one remembered where the crown had been hidden or what had happened to it. Or perhaps there was no statue of the Blessed Virgin to put it on so there was no reason to look for it.

There is no other similar crown in evidence anywhere in the church or on the campus. However, for a period of time following its restoration, after the robbery, the large Crown of the Blessed Virgin was suspended above the Madonna in the Lady Chapel, as pictured. The one now on the Madonna statue in the Lady Chapel, often reputed to be the Empress Eugenie crown, appeared to be embossed gold. A close study of it with binoculars revealed no jewels.

I decided to research the present Madonna statue in order to prove that it was not in any way connected with the missing Empress Eugenie Crown.

In a page by page search of the Scholastic before and during the time the chapels were completed, I made several unexpected finds. The present Lady Chapel with its Madonna was to have been an Our Lady of Lourdes Chapel, a memorial to Father Lemonnier in fulfillment of his deathbed request of Father Sorin. Father Lemonnier was president of Notre Dame when he died on October 31, 1874.

In a letter to the community, Father Sorin writes of Father Lemonnier's last request of him:

. . . But there is one thing in particular which, as a last request, I feel bound to respect; a dying friend's wish presents itself to the living with a special sacredness, claiming, as it were imperiously, an undelayed satisfaction. It was on the eve of his death, as your Reverence is already aware that he entreated me not to refuse the Blessed Virgin the fulfillment of a promise he had made her with your consent and mine, vez, to erect here, if he should be restored, a Chapel of Our Lady of Lourdes: 'For,' said he, 'although I am not going to be cured, I owe her more for dying as I do, then even for a longer life.'(108)

The first library was named for Father Lemonnier. Timothy Howard speaks of him in glowing terms:

Innocence, gentleness, and purity, had a wonderful attraction for his soul. There was nothing which he touched that he did not beautify. He was 35 years old when he died.(109)

The Scholastic goes on to explain the proposed memorial chapel:

The Lemonnier Memorial Chapel dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes will be 45 x 32 in the clear keeping with and in the rear of, the new church. It will be decorated with stained glass windows, and ceiling. It is the intention of the projectors to make it the richest and most beautiful part of the Church of Our Lady of Sacred Heart. Work to be commenced this season as soon as the old church can be taken down to make room for it. In all probability, this Chapel of Our Lady of Lourdes will be, more than any other, the devotional shrine to which inmates and visitors will hourly repair to pray. There before the altar will be kept a constant supply of the precious water from the miraculous grotto in France while along the walls will be hung the ex votos which many pious souls may send in acknowledgement of favors received or solicited.(110)

Donations to Lemonnier's Our Lady Of Lourdes Chapel were regularly listed in the pages of the Scholastic from the time of his death.

From Sorin's first pilgrimage to Lourdes, France in 1873, the focus was on Our Lady of Lourdes. An 1875 Ave Maria reference to the arrival of the sanctuary lamp, completed on December 8, 1874, shortly after Lemonnier's death, was evidence of that fact. The Scholastic(111) also refers to a lamp being presented to the church in memory of Father Lemonnier about this same time.

Undoubtedly, it was also part of Sorin's wish to honor his nephew's deathbed request. This lovely lamp, a replica of the one at Lourdes, is the only one still in existence in the church today. It was refurbished during the last renovation which was completed in 1992 and today graces the newly decreed Basilica of the Sacred Heart.

In the Ave Maria of October 31st there is a description of a wonderfully beautiful Lamp, the gift of the Dioceses of Vivers and Valence, France, to the Shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes. It is a masterpiece of true religious art, designed by M. Bossan, the eminent architect, and executed by M. Armand Calliat, one of the first goldsmiths of France. As the shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes at Notre Dame is to have a similar artistic gem from the same maker, a compendious account of the Lamp may not be considered uninteresting. A detailed description follows with the mention of the wording on the 'circlet of the crown . . . which adorns, without concealing, the crystal chalice which contains the oil. The circlet of the crown is blue, with the inscription, in Latin: 'In Him was Life and the Life was the Light of men.'

The jewels adorning the dragon figures are also described in detail with this added:

Between these brilliant figures there are three shields blue, with a golden representation of scenes in the Nativity of Our Lord wherein He manifests Himself, by light, -- to the shepherds, the Magi, and in His own Divine Person. . . . Three beautiful chains of golden leaves, flowers and blue globules, attached to the dragons' necks, meet above in the inner centre of a reflecting crown, composed of the monogram 'A.M.' (Ave Maria) interlaced with the cross and six broad leaves. From the bottom of the Lamp hang two golden pendants, connected about the middle by a medallion on which there is the following inscription:

THE LAMP

HAS BEEN PRESENTED TO THE SANCTUARY

OF

OUR LADY OF THE SACRED HEART

AT NOTRE DAME, INDIANA

BY

THE DEVOTED FRIENDS OF JESUS AND MARY

IN AMERICA,

AS A TOKEN OF

THEIR FAITH AND BURNING LOVE,

TO KEEP WATCH IN THEIR NAMES

AND

PERPETUATE THROUGH THE DAY AND THROUGH

THE NIGHT THEIR

ADORATIONS, THEIR PRAISES, AND THEIR SUPPLICATIONS

BEFORE THE

AUGUST SACRAMENT OF THE ALTER.

DECEMBER 8, 1874.(112)

This exquisite sanctuary lamp is filled with the finest Italian olive oil and is kept burning day and night in the sanctuary of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart.

It is interesting to note that on May 9, 1874, before Father Lemonnier's death in October, Brother Vincent accompanied Father Sorin to Rome and Lourdes. Brother Kilian Beirne, relates this typically Sorin story about their visit at Lourdes:

In the Basilica at Lourdes Brother Vincent saw the fine sanctuary lamp which was used as a copy for the main sanctuary lamp that hangs today in Sacred Heart Church. Father Sorin admired the lamp and planned then and there to have one made like it -- made by Mr. Armand Caillat, the same artist who fashioned the Lourdes lamp. Then Father Sorin, in a somewhat bantering mood, said to Brother Vincent, 'You'd better get busy and do something for the community before it's too late. I want you to get us a lamp like this one for our new church at Notre Dame.' And Brother Vincent in amazement replied, 'Where would I get $2,000 to buy a lamp like this one?'

'I'm well aware you have no money,' continued Father Sorin, 'but just the same, you must get the lamp.'(113)

Brother Kilian Beirne continues his story:

No doubt Brother Vincent began to pray for a benefactor to help him fulfill Father Sorin's command. . . . In any case, Armand Caillat made a lamp for Father Sorin five centimeters larger than the Lourdes lamp and in every way an improvement on the first and today this genuine work of art hangs before the main altar in Sacred Heart Church. Few members of the Community realize how beautiful this lamp is, because few have ever had a close enough look to see its exquisite workmanship.

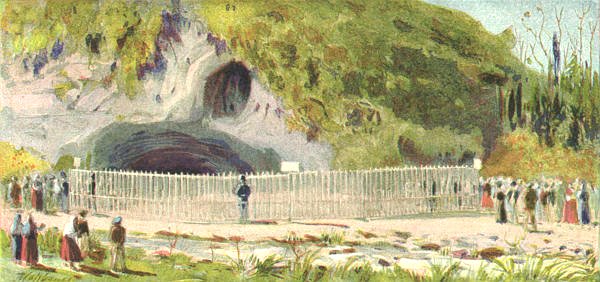

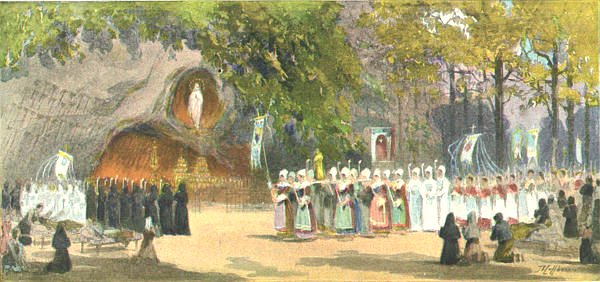

In the intervening 14 years it took to complete the remaining chapels it appears those original plans for the large chapel dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes in Father Lemonnier's memory were modified. Father Sorin built his Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes in 1878. Subsequently, an altar and painting of the Grotto, with a stained glass window depicting Lourdes(114) near it, were placed in a niche of their own and the newly completed chapel, graced with its Madonna statue became the Lady Chapel instead.

A reference to the completion of the Grotto painting in the church appears on September 8, 1888:

Probably the largest representation of the apparition of Our Lady of Lourdes that exists anywhere was lately finished by Signor Gregori in a Gothic angle of the church of the Sacred Heart at Notre Dame over an altar dedicated to the Immaculate Conception. It represents the fifth apparition. The Blessed Virgin stands over a cleft of the rock; the Rosary is suspended on her wrist, and she is about to make the Sign of the Cross. Bernadette kneels at her feet, gazing upward and holding a lighted taper. The stream in the foreground, the rocks and foliage are skillfully painted, and so true to nature as to deceive those entering the church at the main door. The painting is 12 feet wide below and twice as high.(115) -- Ave Maria

The Lourdes altar under the Grotto painting was later removed during one of the renovations.

Eight months after the Grotto painting description appeared, during the month of April, 1889, three brief entries describing the arrival of the Madonna, destined for the Lady Chapel. appeared in the Scholastic. They were small, but they were evidential.

On April 6, 1889, this interesting entry appeared:

A new and artistic statue of the Madonna and child has been placed in a niche in the small tower back of the Minim's chapel in the church. Very beautiful effects are produced by the variegated colors of the windows surrounding the statue.(116)

No one I asked at the church or among the elderly priests had ever heard of the "Minim's Chapel." The chapel described above had always been referred to in the church as the Holy Angels Chapel or more recently the Laetare Chapel. I recalled running across the term "Holy Angels" in my research at St. Mary's in reference to the children taught there. I hunted through my many random notes recorded for no other reason, at the time, then thinking the information might be of value later on. In this 1878 entry, (117) I found the confirmation I was looking for: "Sodality of Holy Angels, 1st organized 1857 by Gillespie, in 1875, was changed from Junior to Minims Dept."

On April 20, 1889, another entry appears:

The Senior Archconfraternity have purchased a handsome statue of the Blessed Virgin which will be placed in the church during the month of May when the students attend May devotions.(118)

On June 2, 1889, yet another, confirming mention:

The new pedestal for the statue, which members of the Archconfraternity recently received from France, is a real work of art.(119)

In those three brief entries, I had found information about the background of the present Madonna statue hidden away in the pages of the Scholastic. It was a gift of the Senior Archconfraternity, was made in France, was placed in its niche in 1889 and is still there today, 104 years later. I had also satisfied myself, it had no connection at all with the missing Empress Eugenie Crown.

Later information acquired about the Madonna statue and the church further confirms this theory. During the last renovation of the church, completed in 1992, the Madonna statue was removed from the niche and repainted. In viewing the statue, now, the crown from a distance appeared to be molded into the statue.

Someone, who was there at the time it was removed from the niche, said he also felt in seeing it close up that it was not separate but a part of the statue. When it was repainted during the renovation the crown and other gold areas on the statue were newly gold leafed.

Perhaps the new statue was ordered with a molded gold crown when the Empress Eugenie crown could not be found. Or, the Eugenie Crown had simply been forgotten in the mood of celebration attending Sorin's Golden Jubilee and the dedication of the new chapels.

From several other sources, I also heard of another curious thing that happened when the statue was removed from its niche. In the bottom of the niche several three dimensional heart-shaped gold boxes made of brass containing prayers and petitions were found. The oldest among them had seven petitions, one was signed by Father Sorin, and dated 1876. With it was a heart made of paper like a small valentine with a picture of the founder. A second one, dated 1878, was from a Sister, signed M.P.B., asking for a happy death. Another dated 1885 included prayers for someone's mother.

Duly noted, I understand they were returned, with the renovated statue, to the niche along with several new petitions. There to reside for perhaps another 100 years. One can only imagine when and how they were placed in the elevated niche, and with the disparity in the dates, where they were before they were moved there in 1889. Could they have once been in the octagonal tower niche of Father Sorin's original 1878 Grotto?

Petitions were also found in hymnals, and under the carpeting of the church near the altar when it was removed during renovation. On another occasion, a slip of paper was said to have been found with what was thought to be the names of early craftsmen who had worked on the church.

I was to learn this is not an uncommon practice among tradesmen. My brother, who is a mason, told me that many times he has written his name on a piece of paper and dropped it into the opening of a cement block or behind a brick. He likened it to a time capsule.

Another interesting anecdote, among those passed on to me in my inquiries about the church, is this story told to me by a former Sacred Heart security guard who said it was told to him by his predecessor, a long time security guard now retired. As the story goes, workmen were preparing to place the heavy marble lid on Archbishop John O'Hara's vault in the church when concern was expressed that someone's fingers might get pinched in the process. The decision was made to take a break for lunch in hopes that a solution would present itself. When lunch was over and they returned the foreman had with him a square cake of ice which was split into four small pieces. One piece was placed on each corner and the heavy marble lid was put in place without difficulty. When the ice melted the task was accomplished. Although I have found no way to confirm it, it was just too ingenious a story to be left untold.

I happened upon another item of interest concerning Cardinal O'Hara in, Reflections in the Dome, in an essay by Edward Fischer. In it, he recalls the vase of 12 red roses, placed at the foot of the tomb of John O'Hara, week after week, as a token of gratitude from the class of 1928.(120)

One other item in the church that frequently elicits comment is the replica of St. Severa. Its origin has always interested me, as I am sure it has others, so I would be remiss in not including the additional information about it I happened upon unexpectedly which indicates it is one of the oldest relics still in existence on campus.

The Portiuncula Chapel

In the Silver Jubilee of the University of Notre Dame, the author, Joseph A. Lyons, speaks of the first little Chapel on the "Island," which was dedicated to Our Lady of the Lake. It was blessed on the 8th of December 1844 and named Most Holy and Immaculate Heart of Mary Chapel. One paddled to the chapel in canoes from the shore of the lake because the neck of land was marshland in the early years. He describes it:

A quaint octagonal Chapel, modest and retired, where the whole community of Notre Dame assembled in times of joy to thank God, and in times of sadness and grief to beg his aid. In 1847, on the 19th of March, it was enriched with the precious body of St. Severa, virgin and martyr (of the third century), given to the Chapel by Bishop Hailandiere, on his return from Rome in 1845. . . . In this chapel, the Archbishop -- then Bishop -- of Cincinnati, the Bishops of Milwaukee and Detroit, said Mass with evident delight.

Mrs. Byerley furnished it with a beautiful carpet and Bro. Francis Xavier taxed his taste and skill to the uttermost to adorn the sanctuary. It moves even such cold hearts as ours is to listen to good Brother Vincent and other of the more ancient Brothers recount the glories of that dear little Chapel. It is now of the past -- but not forgotten. The Chapel of the Portiuncula, with its many privileges, has supplanted it on the "Island." . . . all those who ever had the privilege of praying in the dear secluded sanctuary, remember it with affectionate regret.(121)

In a footnote, Joseph Lyons explains that the mound in the lake was "always known familiarly as The Island, and in the Annals of Notre Dame, this island is named St. Mary's, in honor of the Blessed Virgin."

The replica and the bones of the precious body of St. Severa, virgin and martyr is one of the oldest antiquities at Notre Dame. It now reposes in a glass case among other relics in the Reliquary Chapel of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart.

Like many of the early buildings on campus, this chapel has not survived. (The oldest building presently on campus is Old College, pictured above, built in 1843.) But a second replica of a shrine, the Portiuncula Chapel, also on the island, was completed in 1861. It was a facsimile of the Chapel at Assisi which was originally known as St. Mary of the Angels because of local reports of angelic visitations but it was called St. Mary of the Portiuncula in the mid-sixteenth century. Later both names were used. The chapel was probably built in the tenth or the eleventh century. . . . The church belonged to the Abbey of San Benedetto on Mount Subasio, but it was abandoned late in the twelfth century, until the young Francis repaired it in 1207. There St. Francis received his vocation and founded his first order in (1208), acquiring the Portiuncula from the Benedictines (1210) and having it consecrated (1215?). . . . There he died in an adjacent cell in 1226.

The small Portiuncula Chapel of Our Lady of the Angels was the first replica of a shrine built at Notre Dame (The Chapel of Loretto was built at St. Mary's). It was erected on the "island" in 1861 when the Holy Cross Community obtained the canonical establishment of the Portiuncula indulgences at Notre Dame. In the following years, throngs of pilgrims visited the little Portiuncula Chapel on August 2, the Feast Day of Our Lady of Angels to gain the plenary indulgences. The Portiuncula Chapel, dismantled in 1898, was just the beginning of Father Sorin's interest in placing replicas of shrines at the University to encourage pilgrimages to Notre Dame.

There's an interesting story associated with the Portiuncula Chapel and another, later, Notre Dame notable the sculptor, Ivan Mestrovic, who sculpted the Pieta in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, and many others on campus. This story was told by his daughter, Maria (Maritza) Mestrovic:

In his early career when Mestrovic was working as both an architect and a sculptor, he built an Our Lady of Angels Chapel to keep his promise to a young shipowner's daughter, Maria Racic Banac, before she died. Before she died, after two other members of her family died in rapid succession, she asked her mother to have Mestrovic 'build me a tomb and console me with the thought that death is just a shadow.' As an answer to Maria, the artist inscribed on the bronze bell hanging from the cupola: 'Know the mystery of love and thou shalt solve the mystery of death and believe that life is eternal.'(122)

'Woman under the cross' was another Mestrovic sculpture. All speak of the supreme sacrifice which is also a promise of salvation to those that recognize immortality imprisoned in every soul in love with eternity.

It would appear the precious body of St. Severa was transferred to the first Sacred Heart church when the island Chapel and Novitiate were torn down in 1858.

In the case of the of the missing Eugenie crown, to add further credence to the story, I found evidence of two similar little known stories very much like it:

Among several gifts Napoleon and Eugenie presented to the Notre Dame in 1866 and now displayed in the sanctuary and museum of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, there is yet another in evidence on the University Campus -- a 9 foot telescope with a 6" aperture.

It has a slightly altered appearance from its original state due to the fact that it was housed in an observatory in front of administration building which was destroyed by the 1879 fire. Debris tossed out of the burning building landed on the observatory and damaged a portion of the telescope and its platform. Its base replaced and a its telescope cleaned and repaired, it continued to be used, even after the observatory was abandoned. Then for years it was relegated to a basement storage room, hidden away and forgotten. Many years later it was rediscovered by Professor Schultz and placed on top of the science building where it was used by students to peruse the campus. It remained there, covered by a rough tin shed, until 1993, when once again, it was reclaimed from its obscurity, refurbished, and displayed for a brief time in the Hesburgh Library lobby. Afterward it was again returned to its rooftop perch on the roof of the Nieuwland Science Building where it resides today.(123)

In the same Sacred Heart Church file in the University Archives, under the category of "Crowns, theft of . . ." I found yet another story of interest concerning misplaced treasures clipped from a 1933 South Bend News Times:

A six-foot hand-wrought bronze crucifix, the gift of Napoleon III of France to the University of Notre Dame was "discovered" Saturday by workmen preparing scaffolding for the renovation of the Gregori frescoes in Sacred Heart church.

Someone in the dim past, evidently confronted with the need for an altar crucifix for the apsidal chapel, entered upon the west side of the adoration chapel, and placed the crucifix behind the altar. There it stood, no one knows how many years with only the plain top of the cross showing above the back of the altar. The exquisite design of the carved base could not be seen. No one remembers when the cross was first 'missed.' Its disappearance is paradoxical in that hundreds of people saw it during the years it was lost.(124)

Coincidentally, the last line of this newspaper story could have been written about the Empress Eugenie crown, as well. "Its disappearance was also paradoxical in that many people also saw it, and handled it, during the years it was lost." Fortunately, in the case of Napoleon's crucifix, it was more happily concluded, and today, is displayed in the Laetare Chapel in the church.

Gerbracht sums up his story about the Missing Empress Eugenie Crown with the following observation:

There has never been any reliable evaluation of the crown's location, although it is thought to be along the shore of St. Mary's Lake near the Old College, since that area was used to some extent for dumping purposes during the early days of the University. It's there in the muck of the lake today -- somewhere.

Since the Empress Eugenie crown, has never been found, The Forgotten Crown story seems the only plausible explanation for its disappearance. The story holds up very well and nothing I have found since contradicts it being a true story.

Gerbracht's 1953 story was almost exactly as Father John J. Cavanaugh told it to me, although Father Cavanaugh was not one of his sources and he had never spoken to him about it. The first Father John W. Cavanaugh was president at the time they were searching for the crown. Since Father John J. Cavanaugh was his secretary and closely associated with him afterward, it seems reasonable to conclude that he might have heard of the actual letter when the word reached the campus of its fate.

The only thing different about Father Cavanaugh's account of it and the story excerpted here was its final fate. He told me that being in such a deplorable state, someone in a spring clean-up at Holy Cross Hall had decided to get rid of it by tossing it in the furnace. Hopeful that some of the jewels might still have been intact, trusted workmen had been sent to sift through the remaining ash pile before it was hauled away. In spite of a diligent effort, he said, no remains of it or its jewels were ever found.

Instead, the crown of the Empress Eugenie, wife of Napoleon III, Emperor of France, was to become part of the most valuable ash pile in the history of Notre Dame, destined for a watery grave, its ashes reputedly dumped somewhere in St. Mary's lake. Yet, in memory, it lives on as another choice Notre Dame mystery, a never-to-be-forgotten legend of the early beginnings of the University of Our Lady of the Lake.

**********

The Empress Eugenie Crown and the six-foot bronze crucifix were among many beautiful gifts given to early Notre Dame by Napoleon III and his Empress Eugenie. However, they were all surpassed by another extraordinary gift they were not even aware they had given. It was to become a living legacy -- an intangible gift -- that would benefit people at Notre Dame and throughout the world: For centuries their names were destined to be linked with the Our Lady of Lourdes Grotto at Lourdes and Notre Dame:

Ultimately, Emperor Napoleon III himself intervened to have the barricades removed from the grotto of Massabielle.

Their part in the drama that unfolded at Our Lady's Grotto at Lourdes in 1858, links them forever, with its mystery:

These facts were confirmed, not only in the 1875 book, Our Lady of Lourdes, written by Bernadette's historian, Henri Lasserre; but also in Franz Werfel's book, The Song of Bernadette, based on Lasserre's book 80 years later, which became a classic award winning film.

Lasserre records this episode at the Lourdes Grotto during the time it was barricaded and guarded. The Mayor of Lourdes issued a proclamation. The public was forbidden access to the Grotto. Anyone trespassing on the Grotto grounds or taking water from the Spring would be prosecuted according to law. "Illustrious personages," Lasserre relates, "sometimes transgressed the limits of the enclosure":

. . . a lady had passed the boundary a few paces behind and had gone to kneel against the barrier of boarding which closed the Grotto. From between the opening of the palisade she was watching the miraculous Spring gushing forth and was praying. What was she demanding of God? Was her soul turning itself towards the present or the future? Was she praying for herself, or for others who were dear to her and with whose destiny she was charged? Was she imploring the blessings' and protection of Heaven for an individual or a family? No matter.

This woman engaged in prayer had not escaped the vigilant eyes which represented the policy of the Prefect, the Magistracy and the Police.

The Argus . . . rushed towards the kneeling woman. "Madame," said he, "nobody is permitted to pray here. You are taken in the very act; you will have to answer for this before the Fuge de Paix, presiding over the Correctional Tribunal, and without appeal. Your name?

"Willingly," said the lady, "I am the wife of Admiral Bruat, and Governess of His Highness, the Prince Imperial." . . .

No one in the world had a higher respect for the social hierarchy and established authorities than the formidable Jacomet. He dropped his accusation.(125)

Lasserre does not pursue this interesting factual account further. Werfel, however, eighty years later, proposes -- perhaps by Lasserre's account or further research -- that Madame Bruat by her very admission that she was the Governess of the Imperial Prince, may have been there at the bidding of her Mistress the Empress Eugenie in behalf of the two-year-old Crown Prince, only child of Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie, who might have been ill. And that perhaps, the very devout, Empress Eugenie's influence may have had a great deal to do with the Emperor's change of heart, from stoic disinterest to immediate action. A decree was dispatched "directing that for the future the people should be allowed perfect freedom of action."

Lasserre describes the jubilation:

The town of Lourdes was in a great state of emotion. During the afternoon, the crowd kept going to and fro on the road leading to the Grotto. The faithful, in countless throngs knelt devoutly before the Rocks of Massabielle. They sang canticle, and recited the litanies of the Virgin. Virgo potens, ora pro nobis. They quenched their thirst at the Spring. The believers were free, God had achieved a victory.

Napoleon III and his Empress Eugenie, without knowing it, had given their first gift, an everlasting one, to the University of Notre Dame -- the Our Lady of Lourdes Grotto.

Our Lady had inspired a peasant girl, and moved an Emperor and his Empress -- worlds apart from one another -- to make a difference in the lives of millions of people. Without their actions, the Grotto at Notre Dame would not have existed, because there would have been no Our Lady of Lourdes Grotto in France to inspire it.

Bernadette's experience is expressed in a beautiful hymn at the end of an undated 19th century book about Lourdes. The beginning seven verses and its ending follow:

A Hymn at Lourdes

|

The hour had come for evening prayer;

A hidden Angel walked and met The unwitting steps of Bernadette. Across the mountain stream she hied. A wind in the valley rose and died. Sudden it shook her, sudden it fell. She saw the Virgin on Massabielle. She saw the tender and gentle face Crowned with light that filled the place. It was the Mother of God who smiled Like her own mother on the child. Clad in white was the Lady chaste, A ribbon of Heaven around her waist. The sick, the mourner, the forgiven Come to Lourdes on their way to Heaven.(126) -- Unknown |

These delightful descriptive excerpts from a 1994 Catholic Digest article entitled "LOURDES, More Popular Than Ever," capture Bernadette's fearless faith and her charming colloquial expressions:

A hard-headed, no-nonsense child, she stood up to the civil and religious authorities of her day in recounting the incredible events that took place in the grotto of Massabielle between February 11 and July 16, 1858. . . . One cannot but be struck by Bernadette's sincerity, her common sense, and her refusal to be intimidated by the police, the prefect, the parish priest, or even the bishop. . . . The police inspector and the mayor of Lourdes questioned her and ordered the grotto to be closed, while the local prefect simply accused Bernadette of being crazy. As for the parish priest of Lourdes . . . he could not believe that God would favor a simple woman who was 'incapable of defining the dogma of the Trinity.' . . . Her replies to her numerous and often pompous, interrogators reveal that she was neither impressed by social rank nor suffered fools gladly. She also firmly resisted all attempts at bribery and corruption. Above all, she showed a profound humility. . . . Her whole attitude can be summed up in the remark she made upon entering the convent of the Sisters of Charity at Nevers: 'I served the Virgin Mary as a simple broom,' Bernadette said. 'When she no longer had any use for me she put me back behind the door.'

Alain Woodrow concludes his impressive article with this moving tribute:

Bernadette was not theologically sophisticated. But she nevertheless grasped the essential message of the Gospel. 'See how simple it is,' she said on her death bed at Easter, 1879. 'All you need is love.' That is the true miracle of Lourdes.(127)

Bernadette was 35 when she died. In the movie, Song of Bernadette, her faithful parish priest speaks to her at her bedside:

You are now in Heaven and on earth, Oh Bernadette

Heaven chose you . . .

Now there's nothing you can do except choose Heaven.

M. Armand Calliat, one of the first goldsmiths of France,

maker of the Sanctuary Lamp in the Sacred Heart Church,

also created Bernadette's coffin.