A Cave of Candles / by Dorothy V. Corson

More than a month of concentrated effort going over other files at the Province Archives, the University Archives and the Saint Mary’s Congregational Archives produced my evidence, a folder an inch thick, filled with photocopied letters. It was the kind of evidence hidden away in boxes and overlooked through the years that every researcher seeks to prove historic conclusions.

The emotions expressed in these letters -- the anguished sentiments shared -- along with the frequent annotations in their margins, “destroy this letter,” convinced me that the people who exchanged these letters were eyewitnesses to an historic event worthy of remembrance by both the University of Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s College. This tense ongoing situation extended over more than six years during which time Father Sorin died. Undoubtedly, these years had been filled with so many painful memories for all concerned that when it was over, it was deemed better left forgotten. Within the span of a few years many of those involved had passed away and it soon became past history.

Fr. Corby, who was Provincial at the time, expressed so well -- in a single pithy phrase in one of those letters -- the dilemma facing the University from 1889 to 1895. It suggested that he had already experienced more anxious moments than he cared to count and he was now waiting for the other shoe to fall. In more than one letter, he spoke of a crisis faced by the University and its community of priests, Brothers and Sisters, and ended another letter with, “I feel like a hen on hot ashes.”

The significance of its final outcome viewed in retrospect makes 1896 -- the year the Notre Dame Grotto was built -- memorable for both Notre Dame and Saint Maryís for very different reasons. Leaving the story behind these worrisome events untold, would be to overlook the unfinished good that has evolved since and continues to be actualized today.

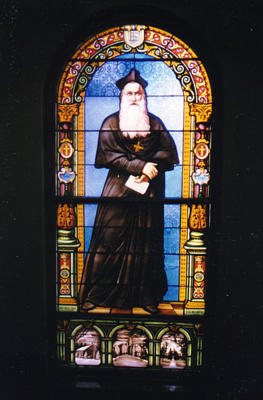

Fr. Sorin himself was well acquainted with the negative and sorrowful aspects of life since more than one crisis on campus, this one included, was of his own making. His own words spoken years before these events took place fit so well this forgotten story I am about to tell, that I feel Sorin would have given his wholehearted permission to share them:

Father Wm. Corby, the Provincial during Fr. Sorinís declining years, was a witness to all that had transpired before and after his demise. Yet, Corby could not have foreseen the impending controversy that was about to engulf the University and its religious community, nor the years of anxiety it would cause him and many other high ranking members of the community, a controversy that threatened to jeopardize the future relationship between Notre Dame and St. Maryís, its sister school.

Father Wm. Corby, the Provincial during Fr. Sorinís declining years, was a witness to all that had transpired before and after his demise. Yet, Corby could not have foreseen the impending controversy that was about to engulf the University and its religious community, nor the years of anxiety it would cause him and many other high ranking members of the community, a controversy that threatened to jeopardize the future relationship between Notre Dame and St. Maryís, its sister school.

Father Sorin’s golden jubilee was celebrated in royal splendor in 1888 but he was getting noticeably older. In 1891 he went to Europe and the Holy Land. He continued to write his inspiring circular letters but his health was worsening. During his last declining years a weakened Father Sorin was no longer able to impose his iron will on the community he had founded. Unbeknown to him, a problematic situation he had put on a back burner had been simmering for years and was about to come to a rolling boil at a time when Sorin was least able to deal with the aftermath of another of his adventurous and unauthorized decisions.

Two publications in the Hesburgh Library stacks supplied the details lacking in the letters to explain how and why this crisis occurred between the two schools. Both publications touch on the events before and during these crucial six years in the history of both institutions but neither one addresses the eleventh hour circumstances or its final outcome. It has been an untold story until now, over a century later.

The first of these publications, a pamphlet titled, The Sisters of the Holy Cross at Notre Dame, was written in 1958 by Fr. Arthur J. Hope to honor the Sisters upon the occasion of their departure from Notre Dame to take up permanent residence at Saint Maryís. Father Hope also wrote Notre Dame, 100 Years in 1948.

Fr. Hope describes the lives of the Sisters at Notre Dame in these excerpts from his booklet, The Sisters of the Holy Cross at Notre Dame (pp 2-6). It was written 63 years after this event occurred. He recounts the early relationship between Father Sorin and the Sisters with good natured humor. No one could have described Fr. Sorinís indefatigable personality and his boundless energy better while still enumerating his flaws.

Father Hope explains that when “these ‘pious women’ [the Sisters] came to America in 1843, they were not religious at all. Fr. Moreau, [the founder of the Congregation of Holy Cross in France], sent with them the request that Father Sorin should try to get some Episcopal recognition for them from the Bishop of Vincennes, Monseigneur de la Hailandiere, [which] he met with ready acceptance.” Father Hope gives his version of Sorin’s part in the conflict:

They placed themselves in Father Sorin’s service. Their duties were endless leaving no time for idle hands.

Father Sorin was very happy to have their services. The zealous and freely given devotion of his community -- priests, Brothers and Sisters -- was the sine qua non which made Notre Dame economically possible. This was the ‘living endowment’ which, from the very beginning brought forth and nurtured the University of Notre Dame.

In the course of a few years for some reason or other . . . the Bishop of Vincennes commanded the Sisters to withdraw from their Notre Dame domicile. The ever resourceful Sorin, consulting the Bishop of Detroit, obtained his consent for the Sisters to live in his diocese. That was the origin of Bertrand, only four miles from Notre Dame. And from there, the Sisters would come back every day, sometimes walking, to repeat their ever growing chores of cooking and washing and cleaning, and return the four weary miles at evening to the new house at Bertrand.

At Bertrand, too, began something that Sorin, in later years, must have regretted: the Sisters opened a school. At that time, Father Sorin did not seriously object: there were still plenty of Sisters to take care of the domestic work at Notre Dame. But the day would come when he would rue the Sisters’ school. Had he not planned that Notre Dame’s very existence and prosperity would depend upon the ever increasing staff of Sisters for washing and cooking and mending? He did not seem to comprehend that here in America, young women with religious vocations would give themselves to that even more necessary work, teaching young Catholics in Catholic schools.

The Sisters, as years went on, gradually worked toward an autonomy which Father Sorin, sensitive on the subject, came to regard as an unseemly rebellion. However, this autonomy was the expressed wish of Father Moreau [the founder of the Holy Cross Order in France]. Had not Pius IX ordered him to separate the temporalities of the Sisters from the rest of the Community? But Father Sorin, ever ready to justify his own dreams, had thought the Pope badly informed, and took his own sweet time loosing the Sisters.

By this time, the Sisters had quitted Bertrand and had built a flourishing school where Saint Mary’s is today. They continued to supply Sisters for the work at Notre Dame. But it soon became apparent that the nuns were not getting enough vocations to continue the ever growing domestic needs of Notre Dame.

Father Sorin, oversensitive and somewhat blind on the subject, intimated that the nuns were shirking their ‘first duty’ it was all very well to open schools and train teachers, but who was to keep the pot boiling at Notre Dame? Who was to make the pies and cook the tough beef? Who would wash and mend and iron?

That valiant woman, Mother Augusta Anderson, headed the Sisters who were seeking emancipation from Father Sorin’s none too gentle tyranny. She won freedom for herself and her group with the assistance of Bishop Dwenger of Fort Wayne. Father Sorin did not take the defeat gracefully, but fostered the determination to have Holy Cross Sisters in ever increasing numbers engaged at Notre Dame. And among the Sisters, there were many who thought their first loyalty was to Father Sorin.

Around this nucleus, Father Sorin, who by this time had become Superior General [of the Congregation of Holy Cross around the world], determined to build a new community. Not entirely new, of course; they would still be Holy Cross Sisters. But he would build for them, on the Notre Dame grounds, a special novitiate where they would be trained in the growing needs of the University. [As chairman of the University Board of Trustees Sorin also became absolute policy maker.]

Mother Augusta [who had taken over the ailing Mother Angela’s duties] pleaded with Father Sorin not to do this, promising that she would make every effort to supply Notre Dame. But the founder of Notre Dame had already made up his mind and, by cracky, no woman was going to interfere with his resolution! He tossed aside Mother Augusta’s reassurance and went ahead on his own. Never again, he wagged his bearded head, would he run the risk of depending on a separate Community!

Fr. Hope goes on to explain:

Mother Augusta who had opposed his plan was abruptly sent [by Sorin] to Utah in 1875. She did not return until the chapter was held in the summer of 1882.

After five years, Father Sorinís ‘oversight’ caught up with him. Rome notified him that the novitiate had been uncanonically made; and that the only remedy would be for all these Ďnunsí to go to St. Mary’s, remake their novitiate, and pronounce new vows to their canonical superior, the Bishop of Fort Wayne! For all his initiative and adventuresome spirit, Father Sorin had to pay now in the bitterness of regret.

And yet God was good to him. He had the grace and good sense to comfort the Sisters [at Notre Dame] who had been so loyal to him, urging them to accept the injunctions of the Holy See. And he promised them that somehow, sometime, they would return to Notre Dame to continue the work so zealously begun. Let them pass through the humiliation (which had been largely his own making), and they would come back to work under his direction once more!

This great group of women, with uncanonical vows, crowded the facilities at St. Mary’s. Mother Augusta and her nuns did their best to make them welcome and to assimilate them. But there was a sort of painful restraint that was never broken down. When they had ‘served their time’ at St. Mary’s they marched back to Notre Dame. They had a sort of fierce loyalty to Father Sorin who, in spite of all his originality and arbitrariness, was able to command their devotion and their service.