A Cave of Candles / by Dorothy V. Corson

Meanwhile at St. Mary’s there was a growing restlessness with the situation and the unauthorized oppressive control Sorin held over the Sisters of the Holy Cross at St. Mary’s.

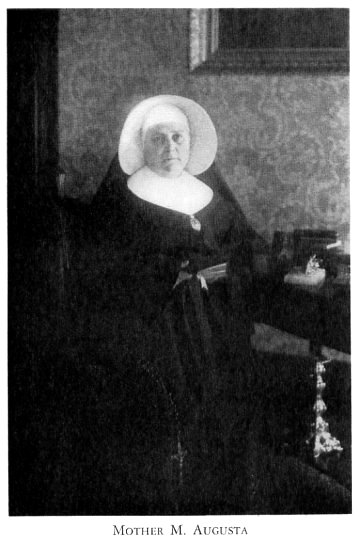

The second publication in the Hesburgh Library stacks, a book, is titled Superior Generals, Volume II Centenary Chronicles of the Sisters of the Holy Cross (pp. 84-104). Of particular interest is the chapter on Mother M. Augusta, first Superior General of Saint Mary’s of the Immaculate Conception who played a pivotal role in this conflict. Excerpts from this book detail the events that transpired on the St. Mary’s side of “the road to Niles.”

It was written by Sister M. Madeleva in 1941, 55 years after the crisis. Mother Madeleva was president of Saint Mary’s College from 1934 to 1961.

Mother Madeleva profiles Amanda Anderson’s origins before she was “clothed in the habit of the Sisters of the Holy Cross and received the name of Sister Mary of Saint Augusta.” In subsequent pages she traces her early years as a nun and her achievements leading up to 1882 when she was elected the first Superior General in the history of the college. She concludes Chapter V with this warm description of Mother Augusta’s last mission at Saint Angela’s Academy in Morris, Illinois before her election as Mother General.

Mother Madeleva begins her chronicle of the impending crisis with these excerpts from Chapter VI entitled:

The Sisters of the Holy Cross had been founded originally to care for the housework in the boarding schools conducted by the priests. Almost immediately they developed into a teaching and hospital order with a distinct genius for education. While solving the problem of domestic economy for the priests of Holy Cross, they presented another of their own autonomy. The solution of this problem is Mother Augusta’s unique service to her community.

From their foundation in America in 1843, the Sisters had been governed directly and exclusively by Father Sorin. He presided at all elections as a matter of course. The bishop of the diocese was not invited and slight advertence was given to ecclesiastical sanction. For more than twenty-five years Mother Angela had acted in one capacity or another as superior, had represented Father Sorin’s authority, and interpreted his will to the Sisters. Her failing health had for some time created difficulties.

From their foundation in America in 1843, the Sisters had been governed directly and exclusively by Father Sorin. He presided at all elections as a matter of course. The bishop of the diocese was not invited and slight advertence was given to ecclesiastical sanction. For more than twenty-five years Mother Angela had acted in one capacity or another as superior, had represented Father Sorin’s authority, and interpreted his will to the Sisters. Her failing health had for some time created difficulties.

The chapter of 1882 called a special meeting of the more experienced and prudent members to consider all aspects of the situation. It was decided to inform the bishop. Bishop Dwenger was a man of uncompromising sincerity, courageous to a fault. He acted immediately. He commanded an election to be held to which the sanction and the blessing of the Church might be given. He counseled the choice of a woman of strong and fearless character who would act according to the laws of the Church for the betterment of her community. He promised suffering and humiliation. He promised, also, a rebirth of the community to a fuller and more perfect life. He insisted that the deeds to property and other important papers belonging to the Sisters of the Holy Cross be put in their possession, and authorized legal assistance if necessary to protect them.

This was the first chapter presided over by a bishop, the first election canonically held. It may be considered the Magna Charta of the community. By a unanimous vote Mother Augusta was elected superior. . . . [The bishop said to her,] ‘I charge you, Mother Augusta, to put on the armor of Christ and to be ready to fight as becomes a soldier of the cross.’ He gave his apostolic blessing to the members of the chapter and returned to Fort Wayne.

Between the years of 1885 and 1889, Mother Augusta was permitted [by Sorin] to remain at Saint Mary’s only intermittently.

Mother Angela acted as superior during these periods of enforced absence. Finally in desperation at her persistent exile, Mother Augusta sent a letter of protest to Father Sorin. He replied advising her to send in her resignation to the bishop. This she did July 24, 1884.

Mother Angela acted as superior during these periods of enforced absence. Finally in desperation at her persistent exile, Mother Augusta sent a letter of protest to Father Sorin. He replied advising her to send in her resignation to the bishop. This she did July 24, 1884.

Her letter brought the bishop to Saint Mary’s posthaste. His Excellency upbraided Mother in no gentle terms . . . without accepting Mother’s resignation. Fr. Sorin was present but offered no explanation. After the meeting Mother Collette insisted that the bishop be told the real state of affairs. Mother Augusta refused. Mother Collette herself reported to His Excellency the petty persecution to which Mother Augusta had been subjected. He recalled the council and reprimanded Father Sorin as ruthlessly as he had reproved Mother Augusta shortly before. Father Sorin remained away from Saint Mary’s for some time after this. Mother Augusta was blamed for his absence. In loyalty to him she could not explain.

Under the date of January 5, 1884, Father Sorin had written that he was “determined to fight with us the good fight to the end.” Only when warp and woof cross can a fabric be woven or any pattern be evolved.

Personal loyalties to Father Sorin were strong. They had the intensity and justification of religious obedience and must be so understood. Eighteen eighty-eight was the year for general election. Owing to a misunderstanding the bishop was not notified in time. . . . By general agreement it was postponed until 1889. On March 2, 1889, the rules and constitution of the community were approved for seven years. Bishop Joseph Dwenger came in person to present them publicly to the council. The entire community was assembled, with Father Sorin present. The bishop had with him all the documents and detailed conditions specified by the Holy See for final approval. He said that permission had been given in 1869 to separate from France. In that year Rome had directed the separation of the priests and Brothers from the Sisters of the Holy Cross in matters both spiritual and temporal. Between 1869 and the approval of 1889, the Sisters were merely an association of pious women under the authority of the bishop of the diocese in which they happened to live.

The difficulties encountered by the bishop in securing the approval of the rules and constitutions are a revelation and an instruction. The chronicle of them should stimulate every Sister to guard a heritage so dearly bought. When the bishop presented himself at the office of the Propaganda, he was told that the authorities there did not care to take up the question; that a community of women that had been directed by a community of men for so many years and had never once made any appeal to the Holy See could not have much desired its approval.

The bishop had tried to explain that the Sisters and he, also, had thought that Father General had arranged all that with the Holy See. . . . Then he was told to look through the letters and papers there which referred to the matter, and to report to Cardinal Simeoni.

In this interview he still insisted that the community earnestly desired the approval of the Holy See and had been made to suffer much in order to have things set right. He related his own experiences in the matter. He was told that Father Sorin was no longer the father general of the Sisters of the Holy Cross. The bishop went on his knees and begged that Father be permitted to retain the title. His request was granted. Father retained the title only. All authority was withdrawn. In the election of 1889 Mother Augusta became the first American Mother General of the Sisters of the Holy Cross according to the constitutions approved by Rome. The community was given one year to withdraw the Sisters from all the houses at Notre Dame, they might remain in the infirmary only.

Mother Augusta was confronted immediately with the conditions specified by Rome. Among those conditions were these:

The Sisters’ novitiate at Notre Dame was to be closed before the fifteenth day of August and all the novices were to be at St. Mary’s on that date. Before the end of the year all the Sisters were to make their allegiance to Saint Mary’s and the Holy See would recognize these professions. Those who refused their allegiance were to take off the habit and return to the world.

The fulfillment of these conditions automatically separated the Sisters from the priests of Holy Cross in administration and all matters spiritual and temporal. It achieved the autonomy, the canonical life, of the community. The process, in terms of personal relations, involved a certain temporary and superficial estrangement. . . . Events have showed how providential, how vital to both communities, was the uncompromising leadership of one intrepid woman.

Mother Madeleva titles her next chapter, “One Fight More,” as she chronicles a crucial move on Mother Augusta’s part and the synchronicity of that meeting.

Saint Mary’s was so crowded that many were sleeping in the halls. . . . The bishop was in broken health. Mother seemed to stand alone. The Holy See was importunate, accusing her of failure to comply with orders given. Finally, after explanation and appeal this compromise was made: The Sisters, after making their submission to Saint Mary’s might remain at Notre Dame as at one of the missions. They were to receive a salary. Saint Mary’s was to provide for their needs. This arrangement [though temporary] continued during Mother’s term of office.

The problem of housework at Notre Dame had become acute. The closing of the novitiate there promised even greater difficulties for the future. The [Notre Dame] council decided before the end of the year to make a last desperate effort to reinstate the Sisters in their original status. Monsignor Satolli was invited to Notre Dame. The case was laid before him. He understood that Mother Augusta had acted in this matter entirely on her own authority. So he came to Saint Mary’s accompanied by the Notre Dame council. The Sisters assembled to meet him. An address was read. Then the Sisters were asked to withdraw. But the monsignor was too wrought up to wait. In a loud voice he said to Mother Augusta, ‘I command you to reopen the novitiate at Notre Dame.’ . . . She answered ‘I must remain true to the trust the community has placed in me.’ He left and returned to Washington.

Mother Augusta called Mother Genevieve and together they walked out on the grounds. Mother Genevieve said that, out of all the hard past, this was the first time she had seen Mother Augusta break down.

Mother Augusta called Mother Genevieve and together they walked out on the grounds. Mother Genevieve said that, out of all the hard past, this was the first time she had seen Mother Augusta break down.

The bishop was very ill. Mother Augusta had no one to turn to. The St. Mary’s council decided to consult Archbishop Elder and Mother Augusta showed him her papers from Rome. He advised her to go to Washington and present her documents [of proof] to Monsignor Satolli.

The Monsignor returned with the letter in his hand. He greeted Mother saying, “Mother, I have come to ask your forgiveness, to beg you to believe me when I tell you that I was deceived, misinformed. Go back to Saint Mary’s with my blessing and my promise that Satolli will never again interfere with Mother Augusta and her Sisters.”

She then learned that the monsignor’s secretary had been the secretary to Cardinal Simeoni and it was he who had handled all the correspondence regarding the community approval from Rome. It was he who had written the Roman letter which Mother had requested him to hand to Monsignor Satolli.

After greeting the Fathers, she was presented by them with a document containing hundreds and hundreds of names of priests and even some bishops, petitioning Rome to reopen the novitiate at Notre Dame. They had made all arrangements to forward the petition to Rome and were now making a last appeal, asking her to put her name to it. For an hour they begged, threatened, trying to make her yield. Finally Mother arose saying, “Fathers, there is nothing more to say. I will never sign it.”

Father Walsh left Notre Dame that night. He had been ill for some time. He died within the year, [July 17, 1893 a little more than three months before Sorin’s death]. One who was with him at the end said that almost the last thing he did was to express regret for having interfered with the Sisters of the Holy Cross. He had done so in obedience.