Notre Dame's Grotto / by Dorothy V. Corson

A Group Work of Art

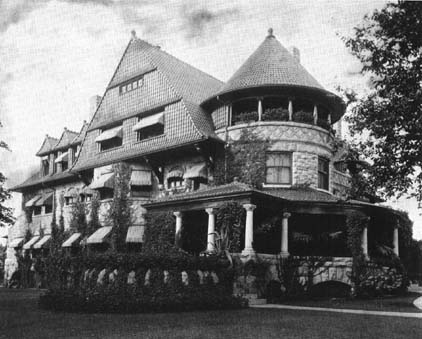

Joan Romine wrote a book entitled, COPSHAHOLM, The Oliver Story, about the building of Copshaholm,(152) the Joseph D. Oliver estate. The house became "a physical link from the stone cottage birthplace of James Oliver. It was named after the village in Scotland from which the family emigrated and means "Clump of trees on a hill overlooking a river."

The stone for the home was gathered in 1895, the exterior was completed and the house roofed that same year. The interior work continued throughout the entire year of 1896. The family moved in on January 1, 1897.

Excerpts from a diary kept by J. D. Oliver's father, the founder of Oliver Chill Plow, are quoted in her book. Copshaholm was also built of stones from the farm fields of St. Joseph County. Joseph's father, James, took it upon himself to comb the countryside in search of stones to be used in his son's new home:

He plunged into the task with the tireless energy and unbounded enthusiasm he had always shown for any of his business projects. Although he was 71, he enthused more over finding a big stone for the house than a small boy would over picking up an arrowhead in the same field.

After locating the stones, James hired teams of horses to dig them out. Often after a huge stone had been hauled from a river bed or farm field and laboriously split, it was found to have some defect and could not be used. It was tedious work. More were rejected because of color, seams or other imperfections than were accepted.

Daily entries in his journal show him hunting stones for Copshaholm, "from March to June of 1895 for the house, and from June to September for the stable." They provide a glimpse of the way a project like the Grotto might have been handled in the spring of 1896, the same year the interior of Copshaholm was being completed. By then, farmers in the area would have been alerted to the value of the rocks in their fields. Many already dug up boulders, rejected for use in Copshaholm in 1895, might have been perfect for use in the Grotto a year later.

Several diary entries give some idea of the magnitude of the task of lifting and transporting such heavy rocks in the days before mechanized heavy duty equipment. Oliver speaks of one day hiring nine teams in all to haul stone.

In some cases, finding 8 and 12 foot stones and resurrecting them from the beds where ice-age glaciers had deposited them centuries before. Men and horses strained to load them. Wagon axles were broken, horses became mired in sand and mud. Occasionally a country bridge broke under the weight, compounding the problem. James Oliver often recorded that five and six horses had to be used on one stone.

Joan Romine also noted in her book the charges made by workmen hired in that era. "Common labor, 15 cents an hour; bricklayers and masons, 35 to 45 cents an hour; carpenters, 20 cents an hour, and stone was sold for one dollar a cord."

Many skilled old country stonemasons would not have been here to build the Grotto if Oliver hadn't brought them to this country from the Polish Province of Germany. These same stonemasons worked in his factory, as farmers worked at Notre Dame, when the weather was too cold to ply their trade.

A noteworthy newspaper article on the subject was written by Jeanne Derbeck for the South Bend Tribune, in 1970. It was shared by Leonard Preuss, a descendant of the Luzny brothers who worked on the Grotto. It speaks of "at least three rare examples of an art that is almost lost:" Tippecanoe Place, the Oliver Mansions and People's Church. Copshaholm would be another example.

She quotes Elmer Hammond, a brickmason and the son of a stonemason, noting that "the secrets of the old craft of stonemasonry are all but unknown today."

"The skill required was unbelievable. The work shouldn't be confused with cobblestone building. Cobblestones are simply picked up out of a field and placed together where they fit. But stonemasons broke large stones to show the colors and beauty inside. Then they put the irregular shapes together to fit perfectly," Hammond explained. "Working only with hammers and the eye -- much like diamond cutters -- stonemasons had to know just how to break the stone to get the best color effect and the right shape."

Hammond recalls that, as a small boy, he would go with his father to work and sit by the bonfire to watch the stonemasons. "They would bring in a wagonload of big stones. Those old-timers could walk right up to them and know right where to hit them. Then they fit them together with such precision that the concave half of an old curling iron was used to make the depression in the mortar between the stones. Sometimes they fired the stones first.

"My father and two uncles had a set of hammers ranging from two pounds to 20 pounds. They had a concave head and wedge-end tip. I remember watching my father take a stone as big as a barrel and blast away at it with hammers. He would even put corners and tapers on it," said Hammond.

Special care was needed to build the arches. "A group of men working together to create an arch like that, measuring solely by eye, -- it's a real group work of art," he said.(153)

Anyone viewing the Grotto at Notre Dame, all these many years later, would have to agree, it is also a "real group work of art."