A Cave of Candles / by Dorothy V. Corson

Chapter 6

The Builders of the Notre Dame Grotto

The pursuit of the background of John Gill, the man recorded as the contractor commissioned to build the 1896 Grotto, became my next research project. The names John Gill and Charles McCoy, his brickmason were listed together in the financial ledgers. However, McCoy's name had simply vanished from the census records. His name appeared in the city directory only until 1898. Property he owned was sold in 1900 and no other records surfaced giving a clue to his whereabouts at the time. Not unusual for the 1890s, because all census records, nationwide, as well as other records were lost in a fire. McCoy passed his property on to an unknown woman for one dollar and was never heard from again. He seemed to have appeared for the building of the Grotto, lived within a block of John Gill on Main Street, and afterward left town for parts unknown.

John Gill, however, was a different matter. In an old 1884 campus work ledger,(48) twelve years before his contract on the Grotto, I found this surprising entry with his signature at the bottom of it: "Hired John Gill to work on St. Joseph Farm for 1 year for $170.00."

I wondered if he might have descendants still living in South Bend. The first name listed in the telephone book proved to be his grandson, Oren Gill, whose property is adjacent to Notre Dame. Puzzled by my call, but most cordial he confirmed that he was indeed the grandson of John Gill and the son of Lawrence Gill, both of whom were brickmasons. "My grandfather was a masonry contractor he said, and my father a mason, but though I tried I never got the hang of it and settled for something else." He was surprised to know that his grandfather had the contract to build the Notre Dame Grotto and said being non-Catholic, as his grandfather was, he had never heard it mentioned before.

Oren Gill was in his eighties now and had no children, but he said his brother, who died in l954, had one child, a daughter, Judy Ladd, who lived in South Bend and was an art teacher at a local high school. He gave me her number and said she was a convert and he was sure she'd find this information most interesting. She was delighted to hear about it, finding it hard to believe, and asked to be kept abreast of any further discoveries I might make along those lines.

John Gill also seemed to have disappeared from the city directory in the late 1890s, which prompted me to pursue his background more thoroughly to be absolutely certain I had the right person. This necessitated another phone call to his grandson and revealed some surprising information that ultimately led to many an afternoon spent in the county clerk's office going over old deeds. Oren Gill related a childhood memory of going out on a buckboard with his brother and sister to see his grandfather who lived on a farm. Now I knew why he had disappeared from the city directory. He moved to the county.

Without a date, I knew it would be just about impossible to locate, so I asked him if he'd mind telling me his age and if he remembered about how old he was at the time. Thus I was able to pinpoint it at somewhere near 1913 at about the same time he said he recalled his grandfather moving to California. Oren Gill chuckled as he related how his grandfather had a touring car, and he remembered as a little boy him telling him how "it went 52 miles an hour and two feet off the ground."

I soon found myself at the county recorder's office looking up deeds for John Gill. There I found not only the property mentioned, 80 acres on the corner of Fir and 23, but also countless other properties in the same general area that proved that John Gill had indeed prospered after building the Notre Dame Grotto.

According to an early plat book he owned 40 acres on State Road 23, on the East side of St. Joseph Valley Cemetery where there are now office buildings, and a mini-market and service station. These properties are just east of the University Park Mall.(49) A cupola house, the homestead that was there at the time, still stands on the corner of Gumwood and Cleveland roads kitty-corner from Gill's 40 acres of land. He owned another eighty acres in Granger where the Juday Creek Estates and Golf course now stand.

In addition, he owned city property on Vistula Road along the river in an area now known as The Edgewater Place Local Historic District, on the west side of the St. Joseph River and Northwest of the Farmer's market. Vistula road, which is now Lincoln Way West, was once known as Mishawaka Road. His family was amazed at the land he had owned, now prime property in the Granger area. It was at about this time, 1913, that he moved to California. On June 22, 1923 he was changing a flat tire when he had a stroke and died.

At the same time, again, while I was in the county recorder's office, I also stumbled upon another property owned by the Kintz family, forty acres along Laurel Road(50) off Auten Road. They sold this earlier property to St. Mary's in 1891, the same year they bought their Talley/Chirhart land from President Thomas E. Walsh of the University of Notre Dame. The money from the sale was used to make the down payment on the purchase of the 80 acres from Father Walsh. This earlier forty acres is still owned by St. Mary's College and is being farmed by them today.

Having established the connection of the Kintz family to the Grotto and the background of the actual builder, John Gill, I expected that it would be a simple task to tie the loose ends together. Unbeknown to me at the time, more pieces were about to be added to the puzzle.

The Architect

While visiting the museum at the Sacred Heart Church one day, I met Brother Dennis Meyers, C.S.C., the University Sacristan. When I spoke of my search for information about the Grotto, he mentioned the name of a woman he knew who often shared her family history and their early ties to Notre Dame.

When I checked it out, she had passed away, but another name was offered as someone who might have the same information, Ann Marger, who I learned later, was also related to Mary and James Roemer, Kintz descendants. She had lots of old time Notre Dame memories to share and to my surprise mentioned my father. She told me her father was also a brickmason and they knew one another. She suggested the person to call was Alice Hennion. "Many times," she said, "I've heard her tell the story of her grandfather being the architect on the Notre Dame Grotto. She would be able to help you with more information."

And so, the name Robert Braunsdorf was added to the list of those associated with the Grotto. This time it was his granddaughter, Alice Hennion, the wife of a George Hennion, a retired Professor of Chemistry at Notre Dame, whose family remembrances supplied me with a most important piece in the Grotto puzzle. It hardly seemed necessary that an architect would be needed but I decided to check the clue out anyway.

She related that her grandfather was a renown architect who built not only the Tippecanoe Place and St. Paul's church in cut granite fieldstone but also many other buildings and homes in the area. She said he also built many buildings on the Notre Dame and St. Mary's campuses and that he had been called in as a consultant on the Notre Dame Grotto. It was then, I recalled again, Father Maguire's letter of correction:

I do not know who the builder was but he had quite a problem when he came to the roof. Many said it could not be built of such rocks; it would collapse. Finally it was decided to try it anyway and a wooden form was constructed and the roof 'keyed.' From its appearance today the work was one hundred percent perfect.

The collapse of the Grotto must have been the reason an architect had been consulted. I recalled reading, several years before, about a woman named Braunsdorf who had been feted on her 100th birthday. Perhaps there was a link here if I could find the members of her family included in the article.

When I obtained the information I needed, I called James Braunsdorf, a Mishawaka High School teacher. I asked him if he was related to this same noted Braunsdorf architect? "Yes," he said, "he was." He told me he had been compiling his genealogy and was gathering his own information on this Braunsdorf ancestor. When I inquired if he had heard of any connection he had with Notre Dame, he told me of the buildings he had built. It was the same information given to me by Mrs. Hennion. He also knew more about this ancestor then I had obtained from the others.

He then told me the story passed down on his side of the family. He said because of his previous work for the University, he was called in to assess a problem they had with the collapse of the Grotto. Apparently, two prior attempts had been made and it had collapsed under its own weight. When timber supports to hold the cemented stones in place were removed the boulders fell down. Braunsdorf was called in to redesign it. He had solved the problem and it had proceeded on schedule. Probably gratis, which might account for the absence of a financial entry in the ledgers I'd studied.

Later, I learned from my brother, Bill Buckles, a mason who worked on the St. Stan's Grotto -- a replica of the Notre Dame Grotto -- that it was built using a 24" wide (approx.) carpenter's arch as a form for the rock arch of the cave opening. The form was removed when the mortar had set. Undoubtedly, Braunsdorf, having once been a carpenter might have done the same thing.

He explained that in the case of the St. Stan's Grotto, built in 1961-62, the cave of the Grotto was built last. After the stone arch, side walls and front of the Grotto were completed, a huge mound of fill dirt was placed behind the arched opening to support the roof of the cave. The stones were positioned and pressed into the dirt which had been smoothed and shaped to form the curved interior of the Grotto cave. Mortar was packed between the stones and 14" - 16" of concrete was then poured over the mortar and stones. Once that hardened, the carpenter's arch and the dirt inside the cave were removed and the stones were cleaned and pointed-up, exposing the rocky ceiling and interior of the cave. (A safe and ingenious way to keep the cave from collapsing while the mortar was setting, as must have happened with the Notre Dame Grotto in 1896 when timbers were used to support the stone.) The dirt was then placed above and behind the completed Grotto and the mound landscaped with ivy, trees and shrubs -- which had not been there before -- giving it the appearance of the natural hillside seen at the Notre Dame Grotto.

Another part of the building of the St. Stan's Grotto was also interesting. At St. Stanislaus, there was no natural hillside to carve out the cave area, because there had been a street there which bordered the church property. Over the years Father Jan petitioned each new mayor with the request to vacate the street. Each time he was refused with the excuse that there were pipes under the streets. After many unsuccessful attempts, Father Jan finally obtained permission to acquire it from Edward Voorde when he became mayor. Without this extra piece of land, there would have been no room to build the St. Stan's Grotto.

On one of my trips to the County-City Building, I noticed the name John Voorde listed as the Portage Township Assessor. Curious if he was related to the former mayor, I asked one day, and learned that he was his son. When I asked him if he knew of his father's connection with the St. Stan's Grotto, he said he didn't, and invited me into his office.

When I told him the story he was pleased to know about it and shared with me remembrances of his family's fondness for the Notre Dame Grotto to add to my collection. He told me his father went to Notre Dame and he was known as Babe Voorde. Later, he was chief football scout for Frank Leahy. He said besides his father Babe, there were three other scouts named Berner, Basker and Beyers and so they were called the 4 B's.

One more startling fact issued from that conversation. I knew his father had an untimely death. He was killed in an automobile accident during his term as Mayor, but I didn't know when. When his son supplied the date, September 2, 1960, another unusual coincidence presented itself. The St. Stan's Grotto was started in 1961 and finished in 1962. My father, William Buckles, died of a coronary occlusion in December of 1963. In both cases, it was one of the last things they did before they died, within a year of their deaths. Without the two of them, it is unlikely that the St. Stan's Grotto, which was inspired by the one at Notre Dame, would have existed. The same could probably have been said about the Notre Dame Grotto if Robert Braunsdorf, the architect, had not been around to solve the collapse problem.

Several items in the family history told to me by James Braunsdorf were also of interest. He said his grandmother told him stories about this great grandfather who also built Tippecanoe Place. She had been a housemaid for Mrs. Studebaker. When she married Braunsdorf's son, Walter, Mrs. Studebaker let them use their cottage at Diamond Lake for their honeymoon. Robert's sons, Walter and William Braunsdorf, were both minims at Notre Dame. William became a carpenter and worked for his father. His son Walter became a plumber.

A copy of Robert L. Braunsdorf's lengthy obituary, sent to me by Alice Hennion supplied additional background on this well known builder of his day. He came from Cooperstown, NY and set up an office in South Bend as an architect.

It confirmed that Robert Braunsdorf was, indeed, a renown New York architect who was hired to build Studebaker's Tippecanoe Place. It also mentioned his connection with both Notre Dame and St. Mary's and the many homes and buildings he had built in the area many of them of cut granite fieldstone. Very possibly the front entrance to the St. Mary's college which was built in 1897,(51) was also his work. The obituary explained the cause of his death at age 58 on December 28, 1901, five years after the Notre Dame Grotto was built. It supported the story that his great grandson James Braunsdorf had told me earlier. His great grandfather was working on the St. Paul's Cathedral when he noticed a huge piece of rose granite which caught his eye. He set it aside and said he was keeping it for his grave marker. His obituary relates:

Shortly afterwards, he was taken seriously ill with intestinal toxemia. The trouble yielded to treatment and in the course of two weeks he was able to resume his duties as supervising architect at the new St. Paul's church. About 10 days ago, however there was another attack with urinary complications and though he recovered sufficiently to be able to sit up, the disease culminated yesterday morning in uremic poisoning which was the direct cause of his death.(52)

The length of his illness had been only 6 weeks. The stone he saved was carved into a beautiful six foot rose granite cross which marks his grave to this day in the Cedar Grove Cemetery on Notre Dame Avenue adjacent to the University.

It is unlikely the Grotto would ever have been accomplished without Braunsdorf's know how. That it is still standing after almost 100 years is evidence of his problem solving prowess. Over the years, a number of his descendants have also been associated with Notre Dame. Again, Father Maguire's letter was almost on target though he obviously did not know who the problem solver had turned out to be, or that it had actually collapsed.

The two men in the photograph at the beginning of this chapter are the builders of the Notre Dame Grotto. The man sitting on the bench is Robert Braunsdorf and the man standing with his foot on the bench is believed to be John Gill.

One Interesting Clue Leads to Others

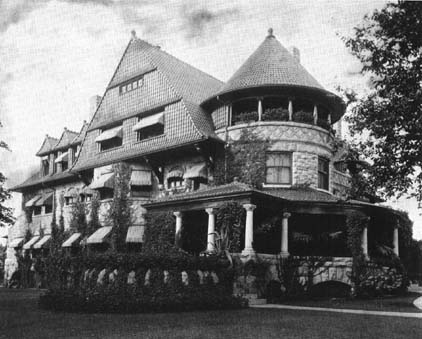

About this same time, I happened upon a book written by a deceased neighbor, Joan Romine, COPSHAHOLM, The Oliver Story, about the building of Copshaholm,(53) the Joseph. D. Oliver estate. I was reading it only because I was planning to visit the historic home for the first time and I wanted to know more about it. The house, I was told, "a physical link from the stone cottage birthplace of James Oliver, was named after the village in Scotland from which the family emigrated and means: Clump of trees on a hill overlooking a river."

I was surprised to learn the stone for the home was gathered in 1895. The exterior was completed and the house roofed that same year. The interior work continued throughout the entire year of 1896, the same year the Grotto was built, and the family moved into Copshaholm on January 1, 1897.

In Joan Romine's book were excerpts from a diary kept by J. D. Oliver's father, the founder of Oliver Chill Plow. Copshaholm was also built of stones from the farm fields of St. Joseph County. Joseph's father, James, took it upon himself to comb the countryside in search of stones to be used in his son's new home:

He plunged into the task with the tireless energy and unbounded enthusiasm he had always shown for any of his business projects. Although he was 71, he enthused more over finding a big stone for the house than a small boy would over picking up an arrowhead in the same field.

After locating the stones, James hired teams of horses to dig them out. Often after a huge stone had been hauled from a river bed or farm field and laboriously split, it was found to have some defect and could not be used. It was tedious work. More were rejected because of color, seams or other imperfections than were accepted.

Daily entries in his journal show him hunting stones for Copshaholm "from March to June of 1895, and from June to September for the stable." They provide a glimpse of the way a project like the Grotto might have been handled a year later in the spring of 1896, the same year the interior of Copshaholm was being completed. By then, farmers in the area would have been alerted to the value of the rocks in their fields and undoubtedly, many already dug up boulders rejected for cut stone use in Copshaholm in 1895 might have have been perfect for use in the Grotto a year later.

Several diary entries give some idea of the magnitude of the task of lifting and transporting such heavy rocks in the days before mechanized heavy duty equipment. Oliver speaks of one day hiring nine teams in all to haul stone:

In some cases, finding 8 and 12 foot stones and resurrecting them from the beds where ice-age glaciers had deposited them centuries before. Men and horses strained to load them. Wagon axles were broken, horses became mired in sand and mud. Occasionally a country bridge broke under the weight, compounding the problem. James Oliver often recorded that five and six horses had to be used on one stone.

Finally, on June 14, 1895, James Oliver reported that the last stone needed for the house was delivered, a large "Pudding stone." This I found in the dictionary to be: "A rock composed of pebbles held together by cementlike stone; conglomerate. A variegated, pudding stone effect." I have yet to locate this particular stone in the Oliver mansion, although I have an idea of what it would look like.

A number of years ago when my brother was building his home on his six acres of former Kintz land, I visited him one day when he was digging his dry well. A small unusual stone resting on a mound of dirt caught my eye. I wrapped it in a Kleenex and put it in my pocket. When I washed it later, I noticed its dark green surface revealed several distinctly separate stones of different colors. Many years later I happened to show it to a friend who had a lapidary gift shop and learned for the first time what it was. She identified it as a miniature pudding stone.

Also noted in Romine's book were the charges made by workmen hired in that era. "Common labor, 15 cents an hour; bricklayers and masons, 35 to 45 cents an hour; carpenters, 20 cents an hour and stone was sold for one dollar a cord."

Joan Romine relates in her book an amusing incident "which tells much about the unpretentious James Oliver," the founder of Oliver Chill Plow:

The story is told that one of the farmers who had stones that James Oliver wished to purchase said he would prefer to wait and be invited to the grand mansion for dinner, as his payment. James told him that it was all right as far as he was concerned but he certainly couldn't understand it. 'After all,' he said, 'mashed potatoes taste the same no matter where you eat them.'

Many of these skilled old country stonemasons would not have been here to build the Grotto had not Oliver brought them to this country from the Polish Province of Germany. Undoubtedly these same stone masons worked in his factory when the weather was too cold to ply their trade.

Evidence of this came into my hands unexpectedly through a man looking for confirmation that his great uncles had worked on the Grotto. He was referred to me by the Indiana Province Archive Center.

I am indebted to Leonard Preuss for additional information, confirming stories I had heard about this family earlier, which produced evidence of additional stone masons working on the Grotto. Along with the obituaries of these men, which will be detailed later, he sent a copy of a noteworthy newspaper article about stonemasonry, excerpts of which, seemed meant to be shared in this Copshaholm portion of my narrative. The man quoted in the article, Elmer Hammond, would not have been known by me as a brickmason who worked for my father had he not sent a beautiful letter to my mother praising my father upon his death. We found it among my mother's treasured keepsakes when she died almost 20 years later.

The 1970 article entitled, "3 Buildings Exemplify Stonemasonry" was written by Jeanne Derbeck. It speaks of "at least three rare examples of an art that is almost lost:" Tippecanoe Place, the Oliver Mansions and People's Church.

Noting that "the secrets of the old craft of stonemasonry are all but unknown today," she quotes Elmer Hammond, a brickmason and the son of a stonemason:

'The skill required was unbelievable. The work shouldn't be confused with cobblestone building. Cobblestones are simply picked up out of a field and placed together where they fit. But stonemasons broke large stones to show the colors and beauty inside. Then they put the irregular shapes together to fit perfectly,'" Hammond explained. 'Working only with hammers and the eye -- much like diamond cutters -- stonemasons had to know just how to break the stone to get the best color effect and the right shape.'

Hammond recalls that, as a small boy, he would go with his father to work and sit by the bonfire to watch the stonemasons. 'They would bring in a wagonload of big stones. Those old-timers could walk right up to them and know right where to hit them. Then they fit them together with such precision that the concave half of an old curling iron was used to make the depression in the mortar between the stones. Sometimes they fired the stones first.

'My father and two uncles had a set of hammers ranging from two pounds to 20 pounds. They had a concave head and wedge-end tip. I remember watching my father take a stone as big as a barrel and blast away at it with hammers. He would even put corners and tapers on it,' said Hammond.

Special care was needed to build the arches. 'A group of men working together to create an arch like that, measuring solely by eye, -- it's a real group work of art,' he said.(54)

When I returned home after my tour of Copshaholm with a friend, I was telling my husband what an enjoyable afternoon we had spent. I began recounting the many interesting features of the house. "Didn't I tell you," he said, "my father's first employer when he came to South Bend during the early 1920s was J. D. Oliver, the builder of Copshaholm. He was his private secretary and later became the Traffic Manager of Oliver Chill Plow. He was in charge of the shipment of Oliver equipment all over the world." It was another unusual connection I hadn't known of before.

Touring Copshaholm, a house steeped in the history of early South Bend, was a rare treat. Most especially because most of the original furnishings are still intact, unusual in a house that old. One cannot help but feel transported back in time to a different era. This landmark house, located in South Bend, IN, gives guided tours and celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1997.

A Charming Little Cottage and More Clues

The next day while driving home from an afternoon of research at the Notre Dame Archives, a little house on Juniper Road -- recently repainted in charming colors -- caught my eye as it often did when I passed by. It had no connection with my research, or so I thought, I was just curious about it. Having just seen Copshaholm, and still feeling its effect, I began to wonder about the history of this charming little house.

It was in an area less than a mile from Notre Dame, and looked like a tiny cottage where an elderly couple might live. A black wrought iron fence enclosed a tiny garden, lilacs bloomed in a hidden corner and two black statues of dogs stood guard at the doorway. As with the Grotto, I'd often wondered who lived there and if the old house had a history but there was no name on the mailbox even if I'd wanted to call and compliment them on it. The fieldstone addition which looked like an old root cellar especially intrigued me. Then suddenly, I realized, I had recently learned in my research that there was a reverse city directory which listed the names of people when only the number was on the mailbox.

I decided not to let another hour go by without paying a compliment to the owner of the house. Pleased to find someone home when I telephoned, I proceeded to pass on the compliment to the woman who answered. I began by telling her how much I admired her home and how I had often wondered about its history. She was happy to hear it and thanked me for making the effort. Instead of the elderly owner I had envisioned living in the little house, I found on the other end of the line Molly Sullivan, a wonderfully expressive personality.

When I inquired about the history of the house what she told me surprised me. She said it was her understanding that it had been a large chicken house on the campus of the University of Notre Dame. One among two moved to Indian Village and remodeled as homes when the University began building more buildings east and north of the campus in the 1920s. She understood that it was moved there by a Chinese man who had owned the China Gardens. He bought it from the University in 1919 and she bought it from his widow some years ago.

It had a full basement and there was a door outside leading to the attic which had rough beams like a log cabin. There were also many bulbs in the backyard and buried garden beds which indicated to her that someone had loved and cared for it. She told me the history of the area was a hobby of hers. She had been a teacher of English Literature at the St. Mary's Academy and also at Saint Mary's college. Her father, Richard Sullivan, now deceased, was an English Professor at Notre Dame. She said more recently she had been working at a studio in Kalamazoo that makes stained glass windows for churches. One of the windows she worked on is in the chapel of the Center for Social Concerns at Notre Dame.

When I inquired about the fieldstone room on the back of her home she said it was built on a cement slab which was there originally. She did not know why it was put there. The fieldstone room was made of cement block with a fieldstone veneer. She had built it herself and she was registered as a working brickmason. She went on to explain that between teachings assignments she had learned bricklaying from a friend who was a mason.

About this time something began to register in my mind. I had heard of a woman brickmason from my brother who told the story of her excellent work with relish. "A great gal," he said. I told her his name and asked if it might have been her. Indeed, she said it was, and her brickmason friend was a friend of my brother's and the two of them had nothing but praise for one another as real craftsmen and regular guys.

This brought up the subject of the Grotto, how my brother had worked on St. Stan's and my recent interest in researching the Notre Dame Grotto. You know, she said, my brickmason friend died, to my sorrow, about five years ago but his sons are brickmasons and paramedics as well. She said she remembered stories this friend told her about his father and grandfather, who were also masons, who worked on the Notre Dame Grotto. "Why don't you call his son," she said, I'm sure he could give you many more details that I don't recall and I'm sure it would be worth your while."

Energized by the unexpected way this new information had found its way into my orbit, I did just that. Nick Kowalski willingly shared his family history with me. He explained, that being a family of brickmasons, it was a common thing to pass on stories while working, and he'd heard the history of his grandfather and great grandfather on a number of occasions. He said they were skilled stonemasons who came from the old country together. They were known as church masons and steeplejacks then. Their passage was paid for by Judge Gary and they had to repay it as indentured servants.

When they arrived in Gary, Indiana they were put to work in the steel mills. Soon they found themselves being taken advantage of and badly treated so they escaped and headed south stopping in South Bend along the way. In South Bend, they worked on Tippecanoe Place, Copshaholm, the house across from it and St. Paul's Church. They were also hired as masons to help build the Notre Dame Grotto. Their names were Nick and Lod (Ladislaf) Kowalski.

I had found no evidence of any other masons, other than McCoy, John Gill's mason, being named in the ledger, yet it did seem reasonable that more than just two brick masons would have been needed. Perhaps any extra masons were paid out of the funds paid to John Gill on the contract, which also might explain why the Kintz men, and any others, were not listed.

What he said next convinced me it was another avenue I had to explore. He said he remembered being told that two or three people died while the Grotto was being built. The Grotto had collapsed a couple times before the problem was solved, and there was a problem, too, with a large stone in the back of the niche though he didn't recall what it was. He also remembered something about the huge stones being unsuccessfully held in place with timbers. Deaths, I knew I could check out in the 1896 newspapers, something I'd already put on my list of things to do. And once again I had a report of the collapse of the Grotto while it was being built.

By this time, I had also begun to collect interesting stories associated with the Grotto. Stories like Tom Dooley's letter encased in Plexiglass at the kneeling rail. I asked this of the paramedic. Did he know of any personal stories or anecdotes about the Notre Dame Grotto. What he told me, I found hard to believe, it seemed such an unlikely story.

He said he had just heard from a friend about a movie that was going to be made about a former Notre Dame student, who was this man's best friend. He was a street kid from Chicago who dreamed of going to Notre Dame and playing on the football team. He didn't have the grades to get in Notre Dame and instead went to the Holy Cross College across the highway from the Notre Dame campus.

As a Holy Cross student he went to the Notre Dame Grotto regularly to pray that somehow, some way, his dream would come true. On one occasion he spent much of the night praying at the Grotto until 6 a.m. He eventually was able to get into Notre Dame. He also got on the football team but spent most of his time on the bench. In the last 27 seconds of the last game of his senior year he got in the already won game of the season, made a tackle, and was carried off the field by the student body who knew him and encouraged his dream.

Hollywood interested in such a sentimental story? It sounded highly unlikely, but I recorded it in my notes anyway. Other than a possible story worth keeping in mind for my collection of Grotto memories, it became another item I stored away for future reference. Six months later I was to find the story was true and a film company would be spending several months on campus filming the story which would be called Rudy.

I eventually met and talked to Rudy Ruettiger and confirmed his Grotto experiences -- an incredible story of inner faith and determination.

An excerpt from an article about the movie Rudy in the Chicago Tribune, written by Joseph Tiber, says it best: "It's a story of courage," said Pizzo the screenwriter. "The most courageous thing an individual can do is to go against expectations, go against identity and definition given by others -- whether it is family or community -- and take that huge leap based on no hard evidence but only an inner faith."

There's an interesting campus connection that the 1931 Lew Ayres movie, The Spirit of Notre Dame -- the only other movie actually filmed on campus -- and Rudy share in common. They both had an association with the Grotto. Evidence of this connection turned up in an obscure booklet I chanced upon while doing my research in the University Archives:

When the Universal Film Co. was preparing the Knute Rockne movie The Spirit Of Notre Dame, (Lew Ayres, 1931) a sound recorder near Our Lady's Grotto caught the uproar of a deafening sky artillery. This gave the Hollywood operators many feet of unexcelled thunder which they insert in various films as the occasion requires. Thus movie fans never know how near they are to Notre Dame, the Grotto and Our Lady. ["University Statue Shrine Stories," (The Kerrville Times, 1943), UQAC, UNDA].

Rudy autographed a photograph of himself and the actors from the movie for me. On it, he wrote three words "Never give up." Those three little words have kept me going on a number of occasions during my research.

A recent trip to view a gallery exhibit at the Northern Indiana Historical Society produced another of those unexpected and unplanned additions while editing these pages. Several years ago in the midst of my research for this chapter I asked about the pudding stone at the Northern Indiana Historical Society. A few had heard of it at Copshaholm, but no one knew its location. My own observations at the time gave me no clues to its whereabouts.

I hadn't seen the Copshaholm gardens in the summertime. It was a pleasant sunny day. I decided to begin at the garden pergola opposite the carriage entrance. I went up the steps to the door so I could view the garden as visitors would view it entering and leaving the porte-cochere entrance. In doing so, inexplicably, my eyes were drawn to the slightly different look of the lintel stone over the door -- a horizontal stone or beam above a door or window to support the structure above it -- which at a casual glance would not have warranted any special attention. A little light bulb went on in my head as I viewed it close-up. It had to be the "pudding stone." Before I had been looking for a large stone used in a decorative way somewhere prominently on the exterior of the house. Instead here it was in plain view being used in a functional way.

Oliver referred to it as a large pudding stone in Joan Romine's book. I began to wonder if it was too large to be used alone and might have been used in more than one place. I soon got my answer and the story it had to tell. I followed the open porch to the front door which had a large window to the right of it. It too, had this large lintel stone over the window. On the left side of the front door were three large bay windows. The same lentil stone was above just the first bay window. When I returned to the first window a close inspection revealed what must have been all that was left of the pudding stone. Two matching pieces about 10" square were inset on each side of the window next to the front door. Oliver had used it wisely. What better place to view it than an entryway.

I was probably not alone in hunting for a decorative pudding stone highlighted somewhere in the exterior walls of the mansion. No wonder it had taking so long to locate. And I had stumbled upon it by sheer chance. This time I wasn't looking for it but it was looking for me. A perfect example of serendipity.