A Cave of Candles / by Dorothy V. Corson

Chapter 7

Two Deaths Associated with the Grotto

Pleased with the additional information I had unknowingly acquired from one random act of kindness, I found myself, the following Monday, at the St. Joseph County Public Library primed to spend as many afternoons as necessary trying to locate the two or three deaths associated with the Grotto.

Over four months of newspapers from May through September was quite an undertaking. I found many unusual stories worth copying to denote the era, but I had not as yet run across much of anything on the Grotto or any deaths associated with it. I repeated my efforts as it was very easy to miss small items over that long a period of time. The passion in those days and the graphic way 1890s newspapers depicted stories was surprising. Among interesting and amusing articles, there were also strange ones.

I was beginning to get a very good picture of the world almost 100 years ago, even what the weather was like. It reached 102 degrees during the time the Grotto was being built. It was an unusually hot summer that spawned violent thunderstorms and a horrendous tornado in St. Louis that was said to have left nearly a thousand people dead. The most common accidents at the time were with runaway horses. There were bodies unearthed that had turned to stone, two of these incidents, ugly lynchings and crimes of passion that were bizarre.

However, the second time around, after another couple afternoons, I did find things I'd missed before. A few lines under the heading, "New Grotto Of Lourdes," announced: "The contract has been let for a new Grotto of Lourdes at Notre Dame to cost about $2,500. It will be constructed entirely of stone."(55)

I found no other mention of the Grotto while it was being built and only a brief mention of its dedication in August. This after going through not only the South Bend Tribune for four months, but also the South Bend Daily Times, the South Bend Times and Mishawaka papers. It was obviously an event that wasn't noteworthy enough at the time to warrant much mention. However, Notre Dame and St. Mary's commencements were written in great detail.

I also almost missed a brief mention in several places of a Michael Presho who had been injured while unloading a wagon of stone:

Michael Presho was engaged in hauling stone to Notre Dame this morning. A large stone had been taken from the front end of the wagon, allowing another large one to remain in the rear. This overbalanced and threw Presho at least 10 or 12 feet into the air. He fell, striking on the wagon gearing and sustained internal injuries. It was thought he was injured fatally, but his physician has hopes of his recovery.(56)

I found nothing about any deaths at the Grotto so it appeared I wasn't going to be able to confirm Nick Kowalski's recent story. I left the library tired-eyed and disappointed that all that time had not produced much at all of any use.

Then while driving home it suddenly dawned on me! I had taken two other items out of the paper I thought might interest Peter, the University Archivist, who was keeping a file of accidental deaths on campus. The South Bend Tribune reported two drownings in the St. Joseph Lake on the Notre Dame campus during the month of June, within two weeks of each other. I had misconstrued what the brickmason's son had said. "Two people died while the Grotto was being built" didn't have to mean at the Grotto itself in the process of building it. If two people had drowned nearby in the St. Joseph Lake someone working on the Grotto would have said just that, that "two people had died while the Grotto was being built," meaning in this case, in close proximity to their work on the Grotto.

There were a possible three people in the brickmason's story. He had said two or three, he wasn't sure which it was. Perhaps the third man, Michael Presho, who was injured at the Grotto, had not survived. This also might explain why there was some doubt about a third death, perhaps these two masons working at the Grotto had not known the outcome of what must have appeared to be a fatal injury. I returned to the library to check out the city directory for the subsequent years and found evidence that Michael Presho had survived what had been described as a serious injury. He was listed as a teamster, a name given to men who drove teams of horses.

I had found my evidence. Though nothing in the records of the campus verified these two Kowalski men as being masons at the Grotto, their knowledge of the deaths was proof positive they had been there. No one else would have had this information to pass on.

Pleased with this unexpected bit of information, I decided to focus my attention on these two drownings in hopes that I might find more hidden evidence. One was Brother Michael Desmaison, an elderly basket weaver who lived on campus. He had gone to the lake to collect reeds for basket making and had somehow stumbled, fallen in, and drowned. He was found the next day in 18" of water by a newsboy walking along the lake.(57)

The second drowning, about two weeks later, was a 19 year old seminarian from Ireland, Lawrence Parnell, who had been swimming alone. Either he had a heart attack or been entangled in the weeds. I checked this out in three papers finding in each of them something different. Even his first name was different in one paper, something genealogists must have to deal with frequently. It may be disconcerting but one soon learns inaccurate historical and media records may complicate a search, but they also train the eye to look for the unexpected. My latest find was also teaching me that perseverance, and digging deeper, usually wins out in the end. Or as someone else has put it: "Errors like straws upon the waters flow / To find pearls we must dive below."(58)

In one newspaper this interesting mention was added to Lawrence Parnell's obituary, "he had a sister who was a Holy Cross nun, Sister Othelia, at St. Mary's."(59) Curious, I decided to see if anyone at the convent knew of this Sister's family and if the name Parnell might be related to the famous Parnell, the poet, and reputed liberator of Ireland. Several inquiries among my elderly Sister friends unearthed a relative. A niece of this Sister Parnell, who was still living at 92 at St. Catherine by the Sea in Ventura, CA. I sent a copy of the obituary to the address given to me for this Sister and was pleased, very shortly, to receive a lovely letter from her thanking me for mine. I've included a portion of it because, it speaks to what was happening when the Grotto was being built:

I was only in the mind of God in 1896 when the sudden and sad death of my uncle, Lawrence Parnell, occurred. I met Sister Othelia for the first time in 1920 in New York after crossing the ocean en route to the Novitiate at St. Mary's. The visit was short but we did full justice to our get together and that same summer we visited Lawrence's grave . . . talked of their rewarding summer in 1896, and their fond goodbyes.

After their visit, she returned to Eureka, Utah and the sad news reached her a short time later. She was not able to return for the funeral. Thank God, He does heal our sorrows with the passage of time. She was a lovely lady, my aunt, and a good friend. She died in 1952.

She said they were not related to the famous Parnell and added this charming closing:

Old age has caught up with me. I find it playing tricks with my memory so do chalk up all errors in my writing to my advancing age of 91 years plus. -- Gratefully, Sister Eutropia(60)

Reading her letter prompted me to locate his grave in the seminarian section of the Holy Cross Community Cemetery where my friend Father Jan is buried. In viewing it, I felt I was reaching back in time, experiencing vicariously, this long dead sister's sorrow at her young brother's death. It brought to mind these poetic words from an old Scholastic: "The flowers of the heart that blossomed then, have never fully faded away. They are still there to be revived and freshened by the dews of memory and the tears of grief."

I tried to imagine the number of feet that had trod the paths from here to there and all the memories attached to every corner of the campus -- the wealth of human history that had left its imprint on the university grounds in over 150 years. A campus friend, Sue Feirick, said it best: "To me, there's no place on this campus that isn't a little bit of heaven."

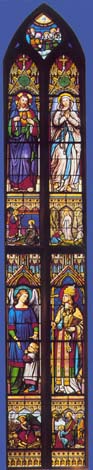

Opposite is a close-up of the Grotto of Lourdes portion of the stained glass window shown at the end of this chapter. It is located on the north side of the west transcept of the Basilica.

**********

Somehow, the above story about Lawrence Parnell would not be complete without this added postscript that occurred while I was editing and printing this chapter. I had not yet gotten to the above portion about Sister Eutropia, which occurred two years ago. I took a break in my editing to visit my Sister friends at the Sisters of the Holy Cross convent at Erskine Manor. It turned out to be a most timely visit.

Another Sister, visiting from California, happened to stop by to look in on my Sister friend while I was with her. Being from California, I asked her if she happened to know Sister Eutropia from St. Catherine by the Sea and she said she did. When I asked her if she would deliver a message to her when she returned to California, she grinned, and said she'd be happy to but wouldn't I prefer to deliver it in person? At the look of surprise on my face, she explained that Sister Eutropia had been transferred to Rosary Hall at St. Mary's College almost a year ago. "Do go and see her," she said, "she is past 93, one of our sweetest Sisters, and she'd be delighted to meet you in person."

It was late afternoon when I left the convent. St. Mary's was on my way home. I decided to obey that "push from within" I was feeling and at least make a stop at Rosary Hall, just in case I might be able to pass on to her, in person, a spontaneous personal thank you for the interesting letter she had sent me two years before. I knew the chances were slim that I'd be able locate her with so many activities going on at the campus in the summertime but I felt it was worth a try.

Happily, she was sitting quietly in their lounge area, reading, almost as if she had been awaiting my arrival. We greeted each other as if we had known one another always and promised to get together again soon for a get-acquainted conversation. She said she had lost my address in moving and hadn't found a sister yet who knew me. She also added one more memory of her uncle's drowning she hadn't included in her letter.

Shortly after she arrived in 1920, she said she was attending a conference given by the chaplain of St. Mary's, Father William (Pop) Connor. He asked if there was anyone in the audience named Parnell. When Sister Eutropia raised her hand, she said he asked her to see him after the program was over. When they met, Father Connor explained that he was Master of Novices in 1896 and was with Lawrence Parnell the day of his death. That he had been hoping one day to be able to tell a member of the family what happened that day.

He explained that he, Lawrence, and another seminarian, were returning together from a gathering on campus. It was an extremely hot summer day. He suggested to the young men that they should take a dip in the lake to cool off. He sat down on the porch of the seminary a short distance away and was engrossed in something he was reading. Suddenly, the other seminarian ran up to him shouting, "Lawrence dived off the pier and he hasn't come up." All attempts to find him in time were futile. He said it took 12 hours to find his body and there was no evidence to indicate why he hadn't surfaced. It was Father Connor, who was also the editor of the Annals of Lourdes publication, who chronicled in great detail the building of the Grotto that same hot summer. This new information revealed another media error. Lawrence did not drown in St. Joseph Lake as reported in the newspaper. The seminary pier is on St. Mary's Lake.

It had taken me no more than 10 minutes to locate Sr. Eutropia at the convent but it was 10 minutes that added a postscript to this part of my story that would not have been here without it. I count it as one more example of that old axiom -- strike while the iron is hot -- wait and it may be too late. If it's a good kind thought, I rarely pass up one of those nagging notions. Perhaps, it is because one time I did, and the person was gone, before I could express those heartfelt feelings we all share in common. Sister Eutropia, being 93 years plus, I was most glad I'd followed this one. Sister Eutropia left this world on January 15, 2000 just shy of her 100th birthday.

Many times, when I have honored these inner promptings -- especially while researching the Grotto -- I have found myself receiving feedback to guide me along the way. Like the answer to a prayer, it's an indescribable feeling that makes you want to walk away whistling.

Another Drowning -- In "Blue Lake"

With each point clarified in Father Maguire's 1953 letter, I found myself getting closer to the actual building of the 1896 Grotto and those closely associated with it.. Obviously, it had not been Father Sorin's Grotto. Where his was and whether he completed it was still a mystery. Father Maguire's comment about it being the site of a rubbish dump and not a beautiful wooded glen had yet to be proven.

However, the collapse stories, now from several sources -- the Kowalski brickmason's story, the Braunsdorf family stories from two different families, 98 year old Brother Vitus, and Braunsdorf's own working connection with Notre Dame -- had been verified. Father Maguire's mention in his letter of a problem and the possibility of a Grotto collapse, indicates he had picked up on something he must have heard, but did not know enough about.

Then another name was suggested to me to contact, Arthur Howard, a former fireman on the Notre Dame campus for 16 years and grandson of Timothy Howard. Timothy Howard was the author of the History Of St. Joseph County, Indiana(61) in two volumes in 1907. It included detailed accounts of some of the notable citizens of South Bend, as well as, the history of Notre Dame and St. Mary's. His grandson, long retired, was now living at the St. Paul's Retirement Home.

Feeling he might have a lot of information and remembrances of his family connection with the campus, I made arrangements to stop by for a visit. I soon learned that Timothy Howard was also a Law Professor at Notre Dame, a Judge, and an integral part of the history of South Bend and Notre Dame, as well. He wrote several books about Notre Dame, among them, a book about its first fifty years, entitled A Brief History Of The University Of Notre Dame du Lac.

Arthur happened to mention that Timothy Howard also had a son who drowned on campus, this time in the St. Mary's Lake. So again, I went back to the St. Joseph County Public Library for newspaper evidence of this drowning. I found this curious item of interest in the text of the article:

The remains were discovered in about four feet of water and some ten feet from the north shore of Blue Lake. In his hand was clutched the walking stick he carried when he left his home. He was 40 years old at his death.(62)

Was St. Mary's lake also referred to as the Blue Lake in 1905? It was an item I decided to check with Arthur. "Yes," he said, "it was called the Blue Lake until more recent times. St. Joseph's Lake also had another name." He couldn't recall at the time what it was, but several nights later I received a phone call from him saying the name had come back to him. St. Joseph Lake was called Mud Lake, though he wasn't sure why, unless it was a nickname placed on it by students. Perhaps it was because it was muddy for swimming or it had a marl bottom similar to St. Mary's Lake. He then explained that many early buildings on campus were built of bricks made from the marl in St. Mary's lake.

In an 1859 Guide To South Bend, Notre Dame and St. Mary's, I found this information:

It had been satisfactorily proven that this marl is superior, for the manufacture of lime, to any that has yet been discovered; and since an improved method of working and burning it has been adopted, the entire surrounding country has been convinced of its superiority even to stone lime, especially for plastering purposes.

Much later, in checking the council minutes for something else, I found mention of marl being sold for $1500, as late as 1889.(63)

Arthur Howard, during his sixteen years with the fire department on campus, was known as Deed to his many friends. In 1925, when Arthur was a young man, his father, who had also been a fireman -- a Capt. with the South Bend Fire Dept. -- was killed on an icy turn where South Bend Avenue becomes Hill Street. His fire truck and a streetcar which had just left Notre Dame bound for the city collided. Once again, Notre Dame family connections merged in marriage. Arthur Howard married a Hickey and his son, Timothy Howard, just retired as an accountant at Notre Dame.

Arthur died just a few months after I visited him and no one seems to know why he was called "Deed." Some say it was because he had a kindly way about him and was always doing good deeds. Some felt it went back to his childhood. Nobody seems to know except that wherever the name came from, he grew into it.

Earlier, I had noticed that many people I talked to had Louis Hickey as a close or distant ancestor. One day I happened upon his obituary in the Scholastic. It carried this mention of his many years of service to Notre Dame:

He was an intimate friend of Father Sorin and his life was closely connected with the University. He cut the first road from Notre Dame to South Bend and spent 40 active years in building Sacred Heart Church and other University buildings. He helped place the big bell in the church tower and his name is inscribed on it. On account of Mr. Hickey's close friendship with the founder of the order and out of respect for a life well spent the huge bell was tolled Tuesday morning."(64)

The huge bell is an impressive sight to see. It is engraved with all the names of those who contributed to its cost, among them many local residents. Mr. Hickey also donated a stained-glass window in the Sacred Heart Church.

In the record of lay persons hired at the University and Farm, in which I located the first work record of John Gill, I also found an interesting earlier record on another member of the Hickey family. It gives some insight into those early times. On December 11, 1873, Eli Hickey signed his mark to an agreement with the University, which states:

Notre Dame agrees to pay 87 1/2 cents per cord for all wood from one foot upward. Said wood to be sawed with cross cut saw, and turned into aged cord wood. Notre Dame furthermore agrees to pay 75 cents per cord for all wood under one foot in diameter. Said wood to be piled in less than one cord in a pile, the whole to be 4 feet in length. The wood is on Mr. Claffey's farm N.E. from Bertrand."(65) -- Signed for Notre Dame by Bro. Francis Desales.

It was an unusual find. I thought its existence might be of special interest to someone in the Hickey family. The Hickey Funeral Home seemed the likely place to leave this information. Thomas Hickey II was most cordial. He was familiar with the piece about Louis Hickey from the Scholastic quoted above, but had not known about the lay person record book. We chatted about the history of the Hickey family. He laughed and said, "It 's an old family saying that if you stand on a corner long enough you'll meet someone related to a Hickey." I had already found this to be true among the many different people I had contacted in my search. A good many of them were linked, in one way or another, to this common ancestor, and ultimately to Notre Dame. I offered to send him a copy of the page from the 1873 work ledger.

As mentioned earlier, my interest in the Notre Dame Grotto stemmed from a replica of it my father built at the St. Stanislaus Church. As our conversation drew to a close, he asked me my father's name. When I told him, he surprised me with the comment that he knew him when he worked for the Hickey Construction Company a number of years ago. He could not have known that he was about to give me another piece in the puzzle I'd long awaited.

More than six months before, I'd given up trying to find a connection between my father and Notre Dame. I had a vague memory of hearing as a little girl that he'd done a lot of work for Notre Dame and the diocese in Fort Wayne but both my parents were gone and none of the rest of the family had any memory of it. Even several elderly brickmasons I'd contacted who had known him could not recall him ever working at Notre Dame.

When I mentioned this side search to Thomas Hickey he immediately supplied the names of two buildings he was sure my father had worked on. "Call my brother, Jerry Hickey," he said, "he was head of Hickey Construction for years, he would know." Another telephone call and I had my answer. He had been the masonry superintendent on three buildings, and possibly more: Zahm Hall, The Infirmary and Breen-Phillips. I had no memory of him ever working for Hickey Construction. My notion to pass on the Hickey information I had found to the family had blessed me with information I was seeking myself.

Sometime later while rummaging through the Scholastics, I found another drowning death in the St. Joseph Lake. In July of 1878, an 18 year old, died two months before he was to become a Brother. His name was James Mulligan, another well known name in the history of the college, whose family was closely associated with the Hickeys and also contributed to many causes on campus. In the Brothers Ledger of Obituary Records I found these comments about him: "He worked hard at the harvest, but did not complain. The very eve of the accident he had said: 'we will rest in heaven, I do not wish to stay long in Purgatory. . . .'"(66)

In this particular case, I came in contact with a member of the Mulligan family in another most unlikely way associated with the Grotto.

Brother Roderic's Grotto Painting

Early in my search, some happening brought to mind a dear Brother friend. He became the caretaker at the Notre Dame Grotto in his twilight years when he was no longer able, due to a stroke, to carry on the constant repair work he did on campus. We usually only greeted one another in passing at Holy Cross House during those busy times, but as his pace slowed we got to know one another better.

I often admired a watercolor painting of the Notre Dame Grotto that hung on a wall at the foot of his bed. When he pointed to himself in it, it intrigued me even more. I could not have imagined, at the time, how it would fit into this Grotto story over a decade later. He said he had been tending the Grotto one day completely oblivious to the person who was painting it. He was about to leave after finishing his work when the artist asked his name and said he had painted him into the picture. He told him he would be getting prints made of the painting and he'd send him a copy.

Brother Roderic said he thought no more about it until one day he was surprised to find a large package had arrived for him. In it, was a 16" x 20" copy of the painting of the Grotto beautifully framed and matted in green. In the middle of it was Brother Roderic in his green and black lumberjack shirt cleaning the wax off the candle holders. He never knew the artist was Franklin McMahon, a well known watercolor painter who has also sketched many buildings on campus. Many times in visiting Brother Roderic in the several years before he died, I admired his Grotto painting.

When he returned from the hospital after a sudden severe stroke I wondered if he would still know me. "He's not responding," the nurse told me, "he's unable to speak, but go in anyway. It might comfort him." Brother Roderic Grix had always been a very serious fellow and I couldn't ever recall him smiling. As I went into his room he seemed not to recognize me or respond in any way. Then, as I was about to leave I recalled a saying he had told me he often used in his letters when he could write them himself.

I spoke to him and told him who I was. Then I added; "Do you know, Brother Rod, there's one thing I'll always remember about our visits and I repeated the phrase, "High on a hill, Carved in a rock, Three little words . . . Forget me not!" To my surprise, though his eyes showed no emotion the corners of his lips turned up in a smile. He never quite recovered from that stroke but we found a way to communicate when others seemed to have no luck. The painting of himself at the Grotto kept him company during his declining years.

He died in the mid 1980s and though I wondered where that lovely watercolor of the Notre Dame Grotto went upon his death, I never thought about it again until I began my own research of its history. Though more than 12 years had passed, since I had last seen the painting, I hoped somehow I might be able to find it, or a copy of it, if it had been published.(67) No one seemed to be of any help in remembering what had happened to it. Most hadn't even noticed it in his room.

I was about to give up on it when I recalled the letters I wrote for him to his sister, a nun, when he was no longer able to do so himself. However, I couldn't recall her name or where she lived. A nurse remembered she was with the Order of St. Joseph and thought she might know what happened to the picture. She directed me to a priest in the house whose sister also belonged to the same order and he gave me her address.

I wrote to her and received a prompt reply. "The information you are seeking is not far away," she said. "The night we went into Brother's room after his death, Mary Grix, expressed the desire to have the picture you asked about. We all agreed she should have it." She told me where she lived, barely two miles from my own home, and suggested I call her.

Mary Grix invited me to come and see it and offered it for copying anytime I wanted it. In the process of getting acquainted with her, I learned her maiden name was Mulligan though she wasn't sure if she was related to the Brother Mulligan who drowned in the lake. Her ancestors, like the Hickey's, were also early helpers who donated to the campus. She said their families were good friends, then and now. Three months later I learned Brother Roderic's sister had died. Had I not acted promptly the information I sought would have been buried with her.

Mary Grix told me her great grandfather, Patrick Mulligan, owned a 200 acre farm that extended from U.S. 31 to Laurel Road. The family owned the property since the early 1800s and she is still living in a home they built on his land. It was her understanding that he donated a stained-glass window in the church and also loaned money to Notre Dame in the early days. In addition, I found evidence that he donated money for the bell in the church and his name is engraved on it. When he died the church was draped in black. She said he was also very fond of the Grotto and never left the campus after church on a Sunday morning without stopping to say a prayer and take a drink at the fountain.

Shortly after our visit I found a reference to the donation of one of those first stained-glass windows in an 1876 Scholastic. It explains beautifully why it was a special privilege to be associated with a church in such a way and records a bit of history worth sharing. Coincidentally, it was donated by yet another Mulligan family thought to be related to the Mulligan Brother who drowned in the lake. It appeared under the title, "Gift of the Edward Mulligan Family:"

The above inscription, printed in large characters on a golden scroll at the bottom of a stained-glass window in the new Church of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, brings back to our minds 'the Ages of Faith,' when crowned heads and princes of Christian blood, as well as the common faithful of inferior rank, esteemed it a singular and precious privilege to see their names immortalized, as it were, the moment they were accepted to be recorded on the walls or pilasters, or on stained-glass windows in the House of God.

Thus, indeed, many a name has been handed down from remote antiquity, to the notice and praises of subsequent centuries, which otherwise would have been long since totally forgotten.

In those happier days of piety, it was justly considered a greater honor to leave such lasting evidence of generous munificence towards God's own House than large estates, or coffers filled with gold, or the coveted wealth the end of all which was so soon to be met in a coffin, save what was done for God's honor and glory.

Time then, as ever, often made woeful changes in human fortunes, and frequently, as even now, great landlords fell from the pinnacle of high offices and honors to the ordinary walks of society; and yet, when reverses had leveled all, the stained glass of a modest or of a grand Church, revealed and transmitted to succeeding ages the lovely evidences that such a family had left an imperishable record of their religion, and their grandsons and nephews could walk into their generous ancestor's temple without a blush, if they had preserved their faith, or keep their heads down, if they had abandoned it. Thus it is that honorable names, long since gone from our midst continue to speak to their descendants the eloquent language of their glorious Faith.

We feel rejoiced that the honor of the first one of these magnificent and classical windows has been secured by the pious family whose name is there inscribed for ages. Mr. Edward Mulligan, now deceased, has left a family worthy of himself. Thirty-five years ago, (1841) to his last moment in 1868, he remained Father Sorin's best friend. His memory is held in esteem and affection by all his acquaintances, and it will be a pleasure to see in this stained-glass window the evidence that his family hold in honor the virtues which he left them as a rich legacy.(68)

When I visited Mary in her home I saw, once more, the Grotto painting I hadn't seen for 10 years. While there I learned other bits of history about her family's connection to Notre Dame I hadn't been aware of before. Francis Grix was her second husband. Her first husband, James Wm. Bookwalter, was a Notre Dame graduate. She described him as a "day student" who used his thumb to get back and forth to campus.

His grandmother was Elizabeth Ruth Higbee, who was the daughter of Daniel C. Higbee, who was the son of Isaac Higbee, who bought a building and property in Bertrand, Michigan in 1836 from a man named Randall who built it in 1824. Randall built it as a hotel. When Higbee bought it, it became a stagecoach stop, general store and post office. He was the postmaster at Bertrand for fifty years. Later it became the Higbee Inn which was burned down by the fire department in the 1970s.

Mary's great grandfather, Patrick Mulligan, was born in a schoolhouse in Ohio. He passed through Ohio and Indiana in 1831 or 32 en route to Chicago. When he got to Dayton, Ohio he was advised not to go. He went anyway but decided not to live in Chicago. Upon returning to Dayton he stopped at South Bend and decided to stay there instead. He owned land near the gate house at St. Mary's.

Mary was a member of the Dig and Delve Club whose members researched local history. She has lovingly cared for all the history of Bertrand, the Higbee Inn and the family, which was passed down through her husband, an only child, to her and their daughters. She was most helpful in supplying information about Bertrand where the Sisters of the Holy Cross began their school when they first arrived in Indiana. She has generously shared not only her remembrances but also countless articles and mementos of the early history of Bertrand when it was a bustling city.

One item in particular about Bertrand touches on Notre Dame history. From the 1876 Scholastic:

The old log church from Bertrand, Michigan was removed to Notre Dame. It was the first church west of Detroit and North of the Ohio River. It will mark the site of the first church built at Notre Dame.(69)

Brother Roderic and his Grotto painting, had contributed new items of interest to my research in bringing to light more old time remembrances of the area.