A Cave of Candles / by Dorothy V. Corson

Chapter 18

Tackling the Coroner's Records

Dr. George Plain, head of the County-City Health Department, who had helped me locate the birth certificate of George Seaton, the scriptwriter of The Song of Bernadette, came to mind. In learning of the drownings on campus during the time the Grotto was being built, he had expressed an interest in knowing of any others I might run across to add to his records. I called to ask him if he knew of another way, other than skimming the newspaper headlines, that I might pursue this latest quest.

Without hesitation, he suggested my checking the County Coroner's records. He explained that the death certificates of a normal death would be signed by an attending physician and would be too numerous to track down without the name of the deceased. However, any accidental deaths, such as drownings, would require an examination by a coroner and those records would be on file.

The County Coroner had only current records which were kept in his office. He said he had no idea where the old records would be. The County/City Archivist who had given me other good suggestions that had produced information on St. Angela's Island agreed that Dr. Plain's suggestion would be the best way to approach it. He then added that I had come along at just the right time. He was in the midst of organizing a lot of old county records in a new archive location. In a few months he would have the coroner's records available to researchers for the first time. It looked like a whole new area to explore before I tackled the actual legend in earnest. Since the line in the newspaper article linked the Indian legend with the so-called curse on the lakes (using the word "perhaps"), I felt it should be proven or eliminated first.

Once again, I found myself venturing into the unknown, researching musty old ledgers containing the coroner's records. One could see by their dusty condition that they had not seen the light of day for a long time. To simplify my search, I worked from 1932 backward since the 1932 "one death a year curse on the lakes" article had said, ". . . up until recently the drownings had occurred with noteworthy regularity."

It seemed highly unlikely that the comment could be factual but having proven two drownings in the lake in one year while the Grotto was being built, I could not just assume that it was a fabricated statement. Fortunately the ledger pages were plainly marked with the cause of death and the place of death. Even without a name to go on, I could easily locate any drownings or accidents associated with Notre Dame or St. Mary's. I found one drowning in 1931, none in '30 and then three in a row, during the years ,1929, 1928 and 1927 then no more for another 5 years. In 1922, 1919, 1915, 1914, 1912, and 1905 another six drownings occurred.

In the space of 30 years, between 1900 and 1931 there were a total of ten drownings, an average of one every three years. Most were in the St. Joseph Lake, the lake still used for swimming. Though the toll was surprising, obviously, the reference to the "one a year" must have been due to someone's bad memory or an overactive imagination. Each old ledger was about 4 inches thick and contained records for approximately two years. It took about an hour to page through one ledger. I decided to check back a little further each way just to satisfy myself I hadn't missed anything. The extra effort clinched it. The next decade in either direction showed no yearly regularity.

So far, it had been a tiresome task, but I had found the proof I needed. I decided to leave it at that and not go any further. I'd just finish the book I was on and not come back the next day. The "death a year in the lakes" was definitely fiction. The curse on Our Lady's lakes had been laid to rest.

Called Back By a Poignant Suicide Note

I was flipping quickly through the remaining pages of the obituary ledger before setting it aside when a folded piece of paper in their midst caught my eye. There had been nothing loose in any of the other ledgers. I assumed it must have been an additional note left by the coroner.

Curious, I unfolded it. A few sentences and I knew at once that it was a suicide note, a local young woman's poignant last words before she took her own life. The words, written in pencil with a clear hand on a child's lined tablet, leaped out at me. Unnerved, I quickly folded it up and put it back in its place. Thinking it was misfiled, I mentioned it to the archivist. He glanced at it, shook his head, and placed it back in the book. I left soon after. A vague memory of her words haunted me the rest of the day and into the evening. I couldn't bring back exactly what she had said. The memory of it seemed to be calling me back to the County Archives, I knew not why, to find out more about her. Ever alert to such nagging notions, I decided to return the next day and go through at least one more book hopeful that the archivist might allow me to make a copy of her note. "Of course," he said, "that's what we're here for."

I set my next ledger aside for a moment, while I hunted through the previous 1933 ledger I'd found her note in. I hadn't noted her name or anything about her at the time but I knew the page would be easy to find because of her note being there. I found it, dated February 25, 1933, opened it up, and once again read her compelling words:

Tell L. H. [the undertaker] to fix me up real nice.

The doctors tell me that there is no hope for my eyes that the one eye will have to be taken out and the other one will soon go blind. My sight is failing me fast. I am so sorry to bother you but its best this way. Don't allow anyone to look at me. If I am sinning may God forgive me. As long as I lived I'd be a burden on somebody. I don't want a lot of crying around. Forget me.

While the archivist was photocopying the unsigned note, I glanced at the page looking for her name. A shiver went up my spine, when up in the corner of the page, I found it: Bernadette P------s. The Bernadette and the February 25th date (the day the spring appeared at the Lourdes Grotto in France) clinched it. It was just too much of a coincidence, not to carry on. Her note seemed meant to bring me back. I had an overwhelming feeling that there was more to come. That there were things I would be missing, if I didn't stay and finish what I had started.

I had already found a half dozen more accidental deaths and drownings associated with the campus in the few years I'd gone through previously. Enough, it seemed, to make it worthwhile to continue. Especially since the effort would not be wasted. The file, "Accidental Deaths at Notre Dame and St. Mary's," at the University Archives contained only a few articles, some of those being the drownings near the Grotto I'd placed there myself earlier.

As long as I had gotten a good start, it seemed reasonable to continue. I decided, on the spot, to go as far as I could in completing their file, in repayment for the help the University Archives had given me, and because of this second Bernadette. It was a name that had already influenced my life in countless ways and seemed to be guiding me again to make this commitment. An additional twenty entries in the next several weeks justified my efforts.

When the Sisters at the convent inquired about my progress and I told them what I was doing. One of them said, "Oh I remember hearing of that curse when I was a little girl, only it wasn't about the Notre Dame lakes, it was about the St. Joseph River. Ah well, I thought, perhaps the writer of the article had also heard of such a curse and attached it to the wrong body of water.

As stories go, it did make some sense. After all, the white settlers had deprived the Indians of their land along the St. Joseph River where many of their villages had been. I recalled being shocked to discover that there were sometimes more than ten drownings yearly in the St. Joseph River, one year there were seventeen, many of them suicides. Old people seemed to end their lives there. Many elderly also ended their lives with illuminating gas which, I learned from the archivist, referred to the gas lights used at the time. The wick would be turned down very low so the gas would escape and they would sleep away.

Several unwanted babies were also disposed of in the river and in other heartless ways. In one case I checked out, I couldn't believe that the doctor and parents responsible were not prosecuted. During the depression, especially, it seems it was not an uncommon practice. The law seemed to look the other way.

I made a note of each drowning or accidental death associated with either campus and then returned to the library to locate, on microfilm, the obituary and any article written about it. Coroner's ledgers earlier than the late 1890s were apparently discarded. It would be six more months before the packets of detailed information that went with the ledgers, would be organized and available for researchers. The Accidental Deaths on Campus file for the University Archives, would very soon be completed.

Early Notre Dame Obituary Ledger

While awaiting my chance to finish the Coroner's earliest records, I happened upon the first, previously unknown, drowning associated with the university, in the Scholastic. This drowning also occurred on February 11, 1874 (Lourdes Day) which, again, seemed to mark it to be included. Though it was not on the campus itself, it happened nearby and gives a glimpse of life at Notre Dame in the 1870s:

A number of students were returning from a promenade through Lowell, when four of them who had remained somewhat behind -- tried to make time and rejoin their comrades by taking a short cut over the race. The race at that point was 10 or 12 feet deep and about 50 feet wide. Three fell in. Cries from the young men soon brought assistance from the neighbors; planks were thrown in and two worked their way out, but one young man, H. Pendill, seemed stricken. All attempts to draw his attention to the plank placed near him were useless. After five minutes of apparent unconsciousness, he went down in spite of the efforts made to save him. It is a pity that a boat was not near at hand, as in that case he might have been helped out. The body was recovered one hour afterward.

We deem it our duty to call the attention of our students to the fact that several students (under age) have been given liquor or wine in the saloon attached to the St. Joseph hotel, and that in many instances, however little they partook of there, they felt sick afterwards. It was the case with H. Pendill, who might be still living had he not drank one small glass of wine in that saloon.

In relation to this sad accident, we also feel it our duty to thank God who has thus far preserved our students from any such winter accidents on our Lakes. This we owe to His kind providence and the care we take to see that our students do not go on the lakes before the ice is strong enough to preclude all possibility of accident.

A few pages further on in the same 1874 Scholastic, where a follow-up of the above item about this incident was recorded, another person's existence was being played out on the stage of life with the mention of another death of a young student two weeks later.

Though the second was not a drowning, the happenstance way I came upon the record of these two 19th century lives lost, seemed to warrant my sharing their stories, that they at least, would not become just cold facts on a coroners ledger. This story recorded in the pages of the Scholastic, 120 years ago, shows the genuine care and concern taken by those who cared for the students, many of them far from home. I share it because it gives another poignant view of the early days of the University when in the European tradition many families sent their children away from home to boarding schools at a very young age.

Death of John O'Brien, of Hartford, Conn.

One whose life had been long despaired of, and only prolonged by the most assiduous attention on the part of the good Sisters of the Infirmary and the skill of Dr. Lundy, passed away from this life to a better one on Wednesday evening, at 9 o'clock.

Master John O'Brien, of Hartford, Conn., had been at Notre Dame for over a year, a student in the Commercial Department. Shortly after the Christmas Holidays he was taken down sick with pneumonia, and soon showed symptoms of his approaching dissolution. For nearly six weeks, his life was prolonged by what appeared a continued miracle. His great courage under his sufferings astonished every one. His father, from Hartford, and friends from Chicago, soon arrived, and bestowed upon him the kindest marks of their affection.

It was the young man's great hope and his father's earnest desire to be allowed to see his fond mother before dying. The danger attending a removal from his bed of sickness -- and above all, the severe ordeal of a winter trip even under the most comfortable circumstances -- could not deter the young man from his purpose, nor prevent his kind father from gratifying his wish. The poor sickly boy left the infirmary but to die at the hotel in South Bend, scarcely one hour after his departure. It was the doctor's advice, the good Sister's wish, and the urgent recommendation of the authorities of the College, that the boy should not be taken away; but they had to yield to father and son. With hearts full of sad forebodings, which were too soon realized, they saw both take their departure for home. In no case could the boy have lived longer than a few days. These he offered up as a sacrifice to the sweet expectation of seeing his mother once more. May this be the case in a better world, where shall be neither suffering nor death, neither absence nor separation. Requiecat in pace.(202)

I was contemplating these sad occurrences, feeling transported back in time to another era so different from our own, when more archival records previously unknown to me came into my hands, again through Peter Lysy, the University Archivist. They were obituary records of early deaths on campus kept in small ledgers from the mid 1840s on. They gave me more information about the earliest drownings on the campus. It had definitely been a detour worth taking. I was about to find more poignant bits of history hidden away in the University Archives.

In perusing them, I found the first two recorded drownings in the lakes before the 1874 St. Joseph River drowning mentioned above, and another after it. A Brother drowned in August of 1854 and a student in June of 1870, both in the St. Joseph Lake. Another previous drowning in the St. Joseph River, a Brother, also occurred in 1870.

When another student drowning in the St. Joseph Lake a year later, in the summer of 1875, was added to the previous three, (four in five years) this notice appeared in the Scholastic on May 27, 1876:

The president of the college has positively forbidden any bathing in the lake this year. Those desiring baths can have them as frequently as necessary, at the bathroom. It is wise to preclude the possibility of another accident like that of last year.(203)

In these same ledgers I learned that the first student death and burial in Cedar Grove in 1847, was the son of an Indian chief, Chief Richardville of the Miamis. All of which further justified my pursuing this latest effort. It was my first evidence of Indian Chiefs being on campus in the early days, information I would need later when I began researching the authenticity of the Indian legend.

In connection with another early death I also happened upon a description of the first student enrolled at the campus on the school's day of opening. The death is undated and it is entered as an Appendix to the Death Notice ledger:

A little boy by the name of John Kelly was drowned in a pond when watering his horse sometime in the year of 1849 or about. He had been at N. D. as an apprentice for several years. He was a good boy but rather inconsistent. He had run away from N. D. not long before the sad accident happened. May his soul rest in peace!

This little boy was smart, but thin and delicate. I remember well how heartily we laughed, good Father Cointet and I when on the day of the opening of the school at the college we saw him on the old road from South Bend advancing slowly towards N. D. carrying on his back in a little white bag, all his fortune. He was the only student who entered the college that day.

There were a few disturbing comments in these early obituaries that haunted my thoughts, afterwards. One description of the death of a young boy, Joseph Henry, in particular, made me wonder about the possible effects and consequences of glorifying death to very young children with impressionable minds:

When asked whether he was willing to die he said, yes. I wish to speak to God and to be with the angels. He promised to pray for everyone there. His mother said he envied his little brother who died being but one year old because he would have been sure not to go to purgatory.

Further on in two other obituaries I found other points to ponder -- the harsh attitudes of religion in those days. Or was it the French origin of the order? The following comments were made about the death of two brothers in 1868:

Rev. James Dillon who died in 1868, left the congregation for the benefit of his mother. Brother Patrick, his brother, did the same and died within weeks. The brother who succeeded him died one month after and they were buried together in the graveyard of the community [underlined in the ledger]. These deaths following so closely are a judgment of God on those who abandon this vocation. A great lesson to religious.

Another much earlier entry pronounced the same harsh judgment on the tragic death of two 12 year old orphan boys in 1854:

These two unfortunate boys, were students at Notre Dame at the time of their death. They were not good boys; they had just run away to South Bend and rather than return to the college they retired at night in an old stable near the bridge. But unhappily the stable took fire (how it was not known) and there they were burnt alive with a horse. This wretched death was looked upon as a punishment. May God have taken these youth in commiseration and inspired them with perfect contrition at the last hour.

The description of the deaths of these orphan boys contrasted markedly with another death in 1866, not unlike John O'Brien's mentioned earlier, whose mother, perhaps reluctantly, also sent her young son far away to boarding school. A common custom during those times among affluent families:

He was taken with fever early in the spring and lingered many long weeks, sometimes worse, sometimes better. His father came to see him about a week before his death, but then he seemed better although little conscious and so the father returned home. Soon alas! the condition of the little patient became worse and George Moran expired after a cruel agony on the 8th of April. His appearance after death was that of an angel, truly beautiful. His body was sent to Philadelphia. It is said that his mother, a Protestant, died almost suddenly of grief very soon after.(204)

One can only imagine the grief and sorrow of the surviving family of this double tragedy, while the orphan boys had no one but the school to mourn their loss.

Among these poignant bits of history hidden away in the University Archives, I found my spirits lifted by the report of an heroic deed associated with one of those untimely deaths that occurred on October 7, 1878, shortly after Sorin's 1878 Grotto was dedicated:

We have this week a melancholy duty to perform in announcing the death of Mr. George W. Sampson, who had just entered on his third year as a student at Notre Dame. His death was caused by the accidental discharge of a fowling piece while he was absent with a hunting party. Mr. Sampson was passionately fond of this amusement, and on Monday last, the first extra holiday of the year, he left the College in high spirits with a few other young men to enjoy a day's shooting in the country and at the same time to try a magnificent new breech-loader which had been presented to him during vacation by his father. While on his way back he met his untimely end. Rev. Father O'Sullivan of Laporte who was on the opposite bank of the St. Joseph River at the time the accident occurred, immediately plunged in and swam across -- though risking his own life thereby -- and was present to soothe the unfortunate man's last moments with the consolations of religion. . . . The incident is one of the saddest ever chronicled in the annals of Notre Dame. A young man of bright promise and of the happiest disposition, gentle and amiable towards all, -- to know young Sampson was to be his friend, and we have every reason to hope that the favorable judgment which all who knew him on earth were so ready to pronounce on him has been ratified above. May he rest in peace!(205)

Students who spent their boyhood on the campus, developed a special fondness for the University of Our Lady du Lac and expressed it upon two known occasions in their requests to be buried in the Community Cemetery for the religious on the road to St. Mary's:

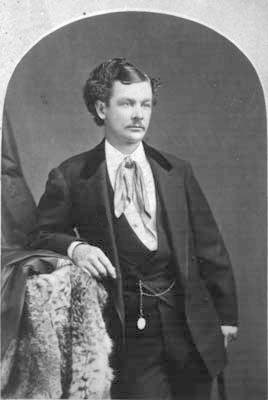

A beautiful monument has been erected at the grave of the lamented Ed. Dunbar, of '63, (1846-1871) in the cemetery near the Scholasticate. It is marble, beautiful in design and artistic in execution. Young Dunbar, it will be remembered was drowned at Waukesha, Wisc. something over a year ago, and was at the request of his parents, buried at Notre Dame where he had passed his boyhood.(206)

A little over a year later, Maurice Williams, a fellow student and boyhood chum of Ed Dunbar, who was dying of consumption, upon his request, was brought to Notre Dame to die. Father Hope writes of this request made of Father Alexis Granger in an article about it in a 1942 Notre Dame Alumnus, in part:

In Father Granger's heart were buried the secrets of Notre Dame boys who, for 50 years, had knelt at his feet and received courage and consolation. It is not an exaggeration to say that Father Granger was THE Father confessor of Notre Dame. No one, before or since has surpassed his record. In the archives today, there exist hundreds of testimonials, the acknowledgment of former students, written in gratitude and affection, the stories of men eternally grateful for the comfort and counsel received at Father Granger's knee.

Father Alexis Granger received a letter from the mother of Maurice Williams in September, 1872:

Dear Father Granger:

I write to make a request of you which is most sorrowful, and yet has its own proper joy in the pious dispositions that prompt it. My child -- my dear son Maurice -- wishes me to beg of you the privilege that he may die at Notre Dame.

The physician who has attended him almost throughout his sickness has pronounced his life as near its close; and ardently desiring to prepare himself with all fervor for the great change that awaits him, he wishes, while his strength is sufficient , to return to the spot where his piety was strengthened during some happy years of his boyhood, and there yield up his innocent life to the God who gave it. At home, where every physical comfort, and most tender domestic intercourse surrounds him, he cannot find that spiritual atmosphere so characteristic of Notre Dame, and for which he longs in the path his feet must tread.

His affectionate heart, it is true, clings to these dear members of his family circle, but, as he said to me a few days ago with tears dropping from his eyes, 'the parting will be bitter, for if I leave them I shall go knowing I have looked my last; but, after all, it will only be anticipating death which will, in a few weeks tear me from them. And oh, I cannot die here where, though I can get the sacraments, I shall not have the daily and hourly comfort of religion that I need. And perhaps God will accept the sacrifice since I make it for my soul.'

Will you accede to his request, and receive him into the infirmary or elsewhere where the sisters and the priests may prepare him for his last end? I will watch over him at night, for while God leaves him to me, I will never leave him . . . . Hoping that your answer may be speedy and favorable, I remain

Truly and respectfully,

Valeria S. Williams

The October 12, 1872, Scholastic announced that the request was granted immediately. The victim of tuberculosis, he died at Notre Dame on the 17th of December, 1872. Father Hope adds a final paragraph and imagines what must have been Father Granger's thoughts as a fit ending to his story:

. . . A life always remarkable for its unwavering and lively faith in the Catholic truths which were his birthright and inheritance, was crowned by a death, peaceful and holy, amidst Religious whose presence and surroundings for the last two months of his life, made his comfort and support in the valley of the shadow of death. His last movements were to wipe the streaming tears from his mother's eyes, and to bid farewell to the priest, faithful and true, whose holy offices in his behalf ceased not in death.

Father Granger went back to the presbytery. His heart was expanded in joy. A Notre Dame student had died well. In his mind, he must have been thinking of something he had often repeated to generations of Notre Dame lads: 'The purpose of a Catholic education is to teach men, not only how to live good lives, but also to die good deaths!'(207)

Ed Dunbar, 25 years old, who gave his life to save a friend from drowning, and Maurice Williams, who was 23, were buried close to one another in the community cemetery, the only students known to have been buried there. In the photograph above, the second large monument marks Ed Dunbar's grave. A monument like the one to the right of Ed's marked the grave of his father, Colonel Richard Dunbar, for nine years. When his mother died, his father's body was moved to Wisconsin so that they could be buried together. The gravesite of Maurice Williams is marked by the first small cross in the same row. Ed Dunbar's sister, who went to St. Mary's, also died young. She preceded him in death and was buried in the Community Cemetery at St. Mary's College.

It appears to have been a special privilege granted to a few layman, mostly professor dons or celebrated personages associated with the campus. There are about seven such graves in the first row of the cemetery behind the front gates. Among them, are two graves of particular interest with touching tributes engraved on their monuments.

On the grave of Professor Joseph Lyons, (1834-1888), who wrote the first history of Notre Dame, is a monument "Erected to his memory as a tribute of the affection of the old students." On it are these added words of tribute: "He was always the same -- kind and gentle sincere and self-sacrificing." His monument is the large one with the cross on the top.

On the beautiful monument marking the grave of Edward L. Greene, (1843-1915) leading American botanist who taught at Notre Dame and left his botany collection to the University is another touching tribute to a man who loved nature:

|

A man whom nature in all her phases attracted and engaged and for whom she opened a door Leading into the House of God. |

To be buried in Our Lady's "island" cemetery, the last resting place of the earliest religious devoted to her name, has become a singular honor shared by the few laymen mentioned above. Seven in all, make up the first row of monuments just inside the gates of the Community Cemetery on the road to St. Mary's. It is all together fitting that two of these burials were two pious students taken in the prime of their lives.